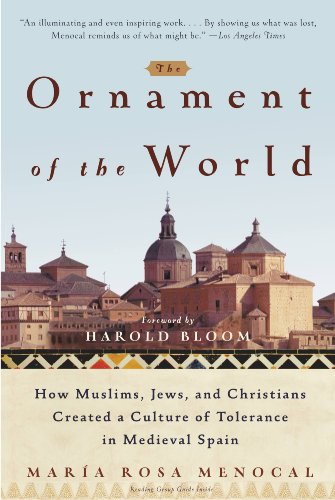

The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews, and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain

by Maria Rosa Menocal

- Author:

- Maria Rosa Menocal

- Status:

- Done

- Format:

- eBook

- Genres:

- History , Nonfiction , Spain , Religion , Islam , Medieval , Middle East

- Pages:

- 315

- Highlights:

- 80

Highlights

Page 146

Menocal’s Andalusia, where “Muslims, Jews, and Christians created a culture of tolerance,” may to some degree represent an idealization, healthy and useful. The author herself refers to the terrible massacre of Jews in Granada in 1066, while ascribing it entirely to fundamentalist Berbers, which is not wholly convincing. Still, the central vision of The Ornament of the World is persuasive. The Jews and Christians of Muslim Andalusia flourished economically and culturally under the Umayyads, whose dynasty had been transplanted from Damascus to Cordoba by the audacious Abd al-Rahman.

Note: Even the foreword writer reckons the author is reaching. It’s like the askhistorians thread said - the truth is somewhere in the middle

Page 201

pioneers throughout history. Abd al-Rahman followed their trail and crossed the narrow strait at the western edge of the world. In Iberia, a place they were calling

Page 201

Abd al-Rahman followed their trail and crossed the narrow strait at the western edge of the world. In Iberia, a place they were calling al-Andalus in Arabic, the language of the new Muslim colonizers, he found a thriving and expansive Islamic settlement. Its center was on the banks of a river that wound down to the Atlantic coast, the Big Wadi (today, in lightly touched-up Arabic, the Guadalquivir, or Wadi al-Kabir). The new capital was an old city that the former rulers, the Visigoths, had called Khordoba, after the Roman Corduba, who had ruled the city before the Germanic conquest. It was now pronounced Qurtuba, in the new Arabic accents heard nearly everywhere.

Note: This city is so old, damn. I can’t recall when the Romans settled it.

Page 209

The local politics had been shaped perhaps most of all by the often murderous rivalries between the majority Berber rank and file and the Arab leadership, rivalries within this community of Muslims whose animus would decisively dominate the politics of al-Andalus—the name used for the ever-shifting Muslim polities of Iberia, never quite the whole of the peninsula—for half a millennium.

Note: I’m in Morocco right now, in a bus listening to Berber music. I wonder how the Arabs set themselves up as the leaders of the Berbers.

Page 214

This was especially so for the majority Berbers, for whom all Arabs were overbearing and brash overlords. Granted, the Arabs had brought the Revelation of the True Faith to these southwestern reaches of the ruined Roman basin—but they had persisted in treating the Berbers as inferiors, even after most had proven to be enthusiastic converts.

Page 228

But during those half-dozen years since the bloody coup, the Abbasids had moved the capital of the Islamic empire farther east, to Baghdad, away from any lingering traces of Umayyad legitimacy. Abd al-Rahman’s improbable and triumphant resurrection as a viable leader was a disturbing loose end, since he was himself the living and vital memory of that legitimate past, with its direct links to the beginnings of Islam itself. Despite whatever dismay the Abbasids might have felt about the Umayyad who got away, they let him be, no doubt reckoning that in the permanent exile in that backwater to which he was condemned, Abd al-Rahman was as good as dead. But this young man was, for nearly everyone in those outer provinces, the legitimate caliph, and he was not about to spend the rest of his life in embittered exile. He built his new Andalusian estate, Rusafa, in part to memorialize the old Rusafa deep in the desert steppes northeast of Damascus, where he had last lived with his family, and also, no less, to proclaim that he had survived and that this was indeed the new and legitimate home of the Umayyads.

Page 261

This book aims to follow the road from Damascus taken by Abd al-Rahman, who, Aeneas-like, escaped the devastation of his home to become the first, rather than the last, of his line. It is about a genuine, foundational European cultural moment that qualifies as “first-rate,” in the sense of E Scott Fitzgerald’s wonderful formula (laid out in his essay “The Crack-Up”)—namely, that “the test of a first-rate intelligence is the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time.” In its moments of great achievement, medieval culture positively thrived on holding at least two, and often many more, contrary ideas at the same time.

Page 283

In the end, much of Europe far beyond the Andalusian world, and far beyond modern Spain’s geographical borders, was shaped by the deep-seated vision of complex and contradictory identities that was first elevated to an art form by the Andalusians. “The ornament of the world” is the famous description of Cordoba given to her readers by the tenth-century Saxon writer Hroswitha, who from her far-off convent at Gandersheim perceived the exceptional qualities and the centrality of the Cordobÿn caliphate.

Note: I remember reading about this on askhistorians. Something about the lamps of Cordoba.

Page 292

Rather than retell the history of the Middle Ages, or even that of medieval Spain, I have strung together a series of miniature portraits that range widely in time and place, and that are focused on cultural rather than political events. They will, I hope, lay bare the vast distance between what the conventional histories and other general prejudices would have us expect (that, for example, Christians saw the Muslim infidels as their mortal enemy and spent seven hundred years trying to drive them from Spain) and what we can learn from the many testimonies that survive in the songs people really sang or the buildings they really put up. These vignettes and profiles highlight stories that in and of themselves seem to me worth knowing and worth retelling as part of our common history.

Page 332

No question in Islam is more fundamental and shaping than this one, a source of political instability and violent dispute from the beginning, as it remains to this day. Who could, after all, succeed a prophet who was also a dominant statesman? In that highly contested succession lie the origins of many of the major shapes and terms of Islam that are mostly unknown or puzzling to non-Muslims: Shiites and Sunnis, caliphs and emirs, Umayyads and Abbasids, all of these crucial internal divisions.

Page 347

Transplanting the heart of the empire out of the Arabian peninsula and into Syria, which had its own mixed cultural legacy, was the first significant step in creating the ill-understood, crucial distinction between things Arab and things Islamic, a distinction that is particularly relevant to our story.

Page 364

The Islamic transformation began to remake the entire ancient Near East, including Persia and reaching as far, already at the time of the Umayyads, as northwestern India. The virtue of this Arab-Islamic civilization (in this as in other things not so unlike the Roman) lay precisely in its being able to assimilate and even revive the rich gifts of earlier and indigenous cultures, some crumbling, others crumbled, even as it was itself being crafted. The range of cultural yearning and osmosis of the Islamic empire in this expansive moment was as great as its territorial ambitions: from the Roman spolia that would appear as the distinctive capitals on the columns of countless mosques to the Persian stories that would be known as The Thousand and One (or Arabian) Nights, from the corpus of translated Greek philosophical texts to the spices and silks of the farthest East. Out of their acquisitive confrontation with a universe of languages, cultures, and people, the Umayyads, who had come pristine out of the Arabian desert, defined their version of Islam as one that loved its dialogues with other traditions. This was a remarkable achievement, so remarkable in fact that some later Muslim historians accused the Umayyads of being lesser Muslims for it.

Page 389

But that became a distant memory—or, rather, something like no memory at all—forgotten during the long period that in European history is most paradigmatically the age of “barbarians.” The cataclysmic upheavals, the pan-European migrations of the Germanic tribes, in the third and fourth centuries C.E., led to the decline and, if not the fall of the Roman empire, at least the loss of both the civil order and the long-term continuity from classical Greece that constituted the heart of our cultural heritage.

Note: Until The Lions have their own historians, the History of The Hunt will always glorify The Hunter.

- Chinua Achebe

The “barbarians” didn’t build monuments or write histories that survived. Hence what we know about them was written by their enemies.

Page 442

The convergence of mixed ethnicity and a religion of converts meant that the ancestors of a Muslim from Cordoba in the year 900 (let alone another two hundred or four hundred years later) were as likely to be Hispano-Roman as Berber, or some measure of each, perhaps with smaller dollops of either Syrian-Arab or Visigothic, these latter two having always been the smaller but politically dominant groups. It was of course the height of prestige to be able to claim, as many would over the years, that one was descended from the original small group of desert Arabs who had first trekked out of the Arabian peninsula or from the Syrians who had led the earliest westward expeditions. Arabness was the most aristocratic feature of ancestry one could want, and Syrian-Arabness was the venerable paternal line of Andalusian culture, both literally and figuratively. But even the emirs, and then their children, the caliphs who were direct and linear descendants of Abd al-Rahman—himself half Berber and half Syrian—were nearly all children of once-Christian mothers from the north, and the pale skin and blue eyes of these Umayyads were regularly remarked on by eastern visitors.

Page 457

One of the most famous documents from this period is the lament of Alvarus of Cordoba in the mid-ninth century detailing the ways in which the young men of the Christian community couldn’t so much as write a simple letter in Latin but wrote (or aspired to write) odes in classical Arabic to rival those of the Muslims.

Page 459

Of course, one can see this adoption of Arabic by the dhimmi—the Arabic word for the protected “Peoples of the Book,” Jews and Christians, who share Abrahamic monotheism and scripture—throughout the rest of the Islamic world. In principle, all Islamic polities were (and are) required by Quranic injunction not to harm the dhimmi, to tolerate the Christians and Jews living in their midst. But beyond that fundamental prescribed posture, al-Andalus was, from these beginnings, the site of memorable and distinctive interfaith relations. Here the Jewish community rose from the ashes of an abysmal existence under the Visigoths to the point that the emir who proclaimed himself caliph in the tenth century had a Jew as his foreign minister. Fruitful intermarriage among the various cultures and the quality of cultural relations with the dhimmi were vital aspects of Andalusian identity as it was cultivated over these first centuries. It was, in fact, part and parcel of the Umayyad particularity vis-à-vis the rest of the Islamic world.

Page 483

From the Andalusian perspective, it had been one thing for the quite reasonably independent Umayyads to pay lip service to the authority of the far-off Abbasids. There had been considerable profit all around from that comfortable arrangement, and free and easy travel back and forth between the rival cities of Cordoba and Baghdad had helped feed the Andalusians’ insatiable appetites for every latest fashion from the eastern metropolis. But by the turn of the tenth century, Cordoba, which from the outset had a distinct sense of its own legitimacy, scarcely imagined itself a provincial capital at all.

Page 510

The rich web of attitudes about culture, and the intellectual opulence that it symbolized, is perhaps only suggested by the caliphal library of (by one count) some four hundred thousand volumes, and this at a time when the largest library in Christian Europe probably held no more than four hundred manuscripts. Cordoba’s caliphal library was itself one of seventy libraries in a city that apparently so adored books that a report of the time indicated that there were seventy copyists in the book market who worked exclusively on copying Qurans. In one of the dozens of pages he devotes to Cordoba, the historian Edward Gibbon describes the book worship of the Islamic polity he so admired (and found incomparably superior to what he saw as the anti-book culture of medieval Christianity) using a somewhat different measure: the catalogues alone of the Cordoba library ran to forty-four volumes, and these contained the librarians’ information on some six hundred thousand volumes.

Page 551

Bitter civil wars among the rival Muslim factions of al-Andalus began in earnest in 1009, and for the subsequent two decades they tore apart the “ornament of the world.” Appalled contemporary observers rather poignantly called those self-destructive years the fitna, “the time of strife.” A culture that not long before had been at the peak of its powers was being brought low not so much by barbarians at the gate as by all manner of barbarians within—within its own borders and within the House of Islam.

Page 569

In part, too, the destruction of Madinat al-Zahra reveals the dramatic divisions among the various communities of Muslims that were part of the struggle to carve out both political and religious legitimacy, and that had been visible a hundred years before, when the Andalusians had declared themselves the true caliphs. Particularly ferocious were the divisions between Berber Muslims from North Africa, traditionally far more conservative, even fundamentalist, and the Andalusians.

Page 579

The full and official dissolution of the Cordoban caliphate came in 1031, slightly more than a century after its optimistic and triumphant proclamation. And although Madinat al-Zahra would never recover, a phoenix of sorts did rise from the ashes of the caliphate in the taifa, or party, kingdoms. In Arabic taifa means “party” or “faction,” and in this case it means a splinter party, a breakaway from the mainstream. In the aftermath of the fragmentation of the caliphate of Cordoba, individual cities and their hinterlands became independent or quasi-independent states and began years of struggle among themselves to acquire the prestige and authority that had once belonged to the now ruined Andalusian caliphal capital. In the early years there were some sixty states of differing sizes and differing political provenances. Some of these were dominated by Umayyad loyalists, others by the old tribal groups who saw themselves as the true Arab aristocracy, others still by Berbers, or even disgruntled military adventurers. As time went by, incessant warfare among these rival cities winnowed the survivors down to a powerful few.

Note: The wealth flows from peace and trade. All these dudes were fighting to restore the wealth and power alAndalus, but they only succeeded in dooming it.

And yet, as the following chapter shows, the fall of Cordoba meant the movement of people who made the whole peninsula cosmopolitan. It’s hard to say if this would have happened if Cordoba hadn’t fallen.

Page 594

Precisely at this point also, the northern Christian territories began to consolidate as unified and increasingly powerful kingdoms. Expanding slowly southward throughout the eleventh century, the Christian-controlled cities were in the same general melee of competition for territories and widespread leadership and cultural prowess as the Muslim cities. The Cid, an ambitious military adventurer (who would enjoy a long career in Spanish myth and legend), lived and led his various armies into all manner of battles at this time, when religious rivalry was more an ideological conceit than any kind of determining reality. Rodrigo Diaz, known by his Arabic epithet—El Cid comes directly from al-sayyid, meaning “the lord” in Arabic—had military successes chronicled admiringly by Muslim as well as Christian writers, just as he fought in the service of Muslim and Christian monarchs alike. Likewise, Muslim cities at times paid tribute to more powerful Christian neighbors, just as Christian kings at times found their most loyal allies among Muslim princes or emirs.

Page 630

Within the Iberian Peninsula, the tumultuous period of the independent Muslim cities of al-Andalus came to an end with an event characteristic of the times. Alfonso VI of Castile, a politically astute and highly ambitious Christian monarch and longtime protector of the critically important Islamic taifa of Toledo, consolidated his power and took overt and official control of that ancient city in 1085. Victor over Christian and Muslim adversaries alike in his bid for leadership over broad territories, Alfonso made Toledo his new capital. He also made it the heir apparent to some of the lost glories of Cordoba and al-Andalus. Alfonso and his line of influential successors became the patrons and proselytizers of much of Arabic culture, and of the vast range of intellectual goods that were subsequently made accessible to the Latin West. Toledo was made over as the European capital of translations and thus of intellectual, especially scientific and philosophical, excitement.

Page 636

But to the south, Toledo’s takeover by a powerful Christian monarch who was a real contender, not just another strongman of some minor city, provoked a historically fateful military reaction. Alfonso’s defeated and dismayed rival for control over Toledo, the equally ambitious and accomplished Mut amid, based in Seville, asked for military help from the Almoravids, the fundamentalist Muslim regime that had recently taken control of Marrakech and established the polity we know as Morocco. The Almoravids were Berber tribesmen who had been building a considerable empire in North Africa. These fanatics considered the Andalusian Muslims intolerably weak, with their diplomatic relations with Christian states, not to mention their promotion of Jews in virtually every corner of their government and society. But the somewhat deluded Mutamid of Seville cared little about their politics, and imagined he could bring them in to help him out militarily and then send them packing. The Almoravids thus arrived ostensibly as allies of the weak taifas and quickly succeeded, in 1086, in defeating Alfonso VI. These would-be protectors, however, stayed on as the new tyrants of al-Andalus. By 1090, the Almoravids had fully annexed the taifa remnants of the venerable al-Andalus into their own dour and intolerant kingdom. For the next 150 years, Andalusian Muslims would be governed by foreigners, first these same Almoravids, and later the Almohads, or “Unitarians,” an even more fanatic group of North African Berber Muslims likewise strangers to al-Andalus and its ways. Thus did the Andalusians become often rambunctious colonial subjects in an always troublesome and incomprehensible province. They had irretrievably lost their political freedom, but the story of Andalusian culture was far from over: although bloodied, the Andalusians were unbowed, and their culture remained their glory—viewed with suspicion, yet often coveted by all their neighbors, both north and south.

Note: The entire el Cid campaign.

Page 658

This period is also the beginning of the end of hundreds of years of open Islamic and Jewish participation in medieval European culture. The years of colonial status, from the Almoravids’ 1090 annexation on, were unhappy ones for the Spanish Muslims. The Almoravid attempts to impose a considerably different view of Islamic society on the Andalusians provoked relentless civil unrest: in 1109, not even twenty years after these newcomers had been invited in as allies, anti-Almoravid riots broke out in Cordoba following the public book-burning of a work by al-Ghazali, a legendary theologian whose humane approach to Islam, despite its orthodoxy, was too liberal for the fanatical Almoravids. Such violent disagreements about the nature of Islam were far from unique. Equally striking was the resistance against various Almoravid government attempts to control and even persecute the Sufis, mystics deemed far too heterodox by the Almoravids but much admired by the Andalusians. The generally turbulent religious climate in al-Andalus drastically changed the composition of Muslim cities. A significant flight of the dhimmi, the Jews and Christians who had been a vital part of the vivid and productive cultural mix, now began. Regrettable as all this was, still worse was to follow: an even more repressive Muslim Berber regime overthrew the Almoravids in North Africa, and kept al-Andalus as its own colony. The Almohads’ brand of antisecular and religiously intolerant Islam was at irreconcilable odds with many Andalusian traditions, and they ultimately failed in their attempts to “reform” their colonized Muslim brethren. Nor were they able to achieve anything like the sort of ideologically based political unity they demanded among Muslims, a failure with grave political consequences.

Note: I’m going to guess that most of the examples of persecution of Christian’s and Jews were under the fundamentalists. And the author points out that the Muslim andalusians were also put on by the fundies. They were all suffering.

Page 681

Once again, in a parallel to the events within al-Andalus that led to the destruction of the once vibrant Islamic society, the enemies here were as often within as without. With his grandiose visions of universal dominance over political enemies (Christian heretics and Muslim infidels alike), Innocent was a pope of unrivaled political reach who provoked wide-ranging changes in Europe’s cultural and ideological landscape. Innocent’s iron fist was also directed at what seemed to him a motley crew indeed, the Christians of the various and sundry kingdoms south of the Pyrenees. Here was a collection of disunited and all too heterodox Christians so lackadaisical in their faith that they permitted Jews to live indistinguishable from them in their midst, eventually even ignoring the 1215 decree of the Fourth Lateran Council, over which Innocent presided, that stipulated that Jews wear distinctive clothes or other external markers of difference. These were Christians who, most of the time, would just as soon fight each other as wage crusade against their Muslim enemies next door.

Note: I don’t much care for Innocent III. Doesn’t seem like a good dude.

Page 697

When Ferdinand died a few years later, his son Alfonso—who would be called “the Learned” and be the great patron of translations and thus of the transfer of the AraboIslamic fortune into the treasury of Christendom—built for his father a tomb to sit in the Great Mosque of Seville, which had been reconsecrated as the splendid cathedral of the new Castilian capital. Alfonso had the tomb inscribed, in the spirit of the age, in the three venerable languages of the realm—Arabic, Hebrew, and Latin—as well as in the upstart Castilian that only poets and other revolutionaries were writing in just yet. But the world within which Ferdinand’s tomb made sense, that first-rate world in which all those languages sat comfortably next to each other carved on the tomb of a Christian saint, was eventually destroyed, along with the mosque that originally housed it, and inside which not only Ferdinand but his successors prayed until well into the fifteenth century. The fitful dismantling of that universe, the hows and whys of the disappearance of this first-rate European culture is really a different history from the one that concerns this book, and it is a long and often treacherous road that winds from Ferdinand III’s Seville in 1248 to Ferdinand V’s Granada in 1492.

Page 706

Ferdinand III had, in effect, created Granada as the last Islamic polity on the Iberian Peninsula: it had been the reward given to one Ibn Ahmar, of the Nasr family, in return for much-needed military assistance in the battle for Cordoba that the Castilian had waged against the Almohads in 1236. The Nasrids, the descendants of Ibn Ahmar, survived the Iliad-like 250-year siege that followed, not as Andalusians proper but rather as keepers of the memory of al-Andalus and, increasingly, as the builders of its final sepulchral monument, called the Alhambra. On a spot already inlaid with layers of memories, the Alhambra ultimately became the setting for the highly charged scenes that set the stage for the true end of the Middle Ages in 1492: Muhammad XII, the last of the Nasrids, known as Boabdil, handed the keys of his family’s royal house to the descendant of Ferdinand III and Alfonso the Learned, Queen Isabella of Castile, and her husband, Ferdinand of Aragon. Some recountings of that story say that the Catholic Kings were dressed in Moorish clothes for the occasion, and perhaps they were also dressed that way just a few months later, when they signed the decree expelling the Jews.

Page 731

In Iberia the Visigothic settlements that the Muslims had moved into were far from well tended. But part of the Umayyad tradition, developed in Syria when they had first arrived there, was to know how to take advantage of what they found lying about, especially when it came to the abundant remains of the Roman past. What could be salvaged was salvaged and reused; what had to be newly invented was. Bridges and roads were built or repaired; and water was brought to the land so new kinds of plants could be cultivated. In many cases these were themselves the fruits, both literal and metaphoric, of the eastward Islamic expansions, to places such as Persia and India, whose many riches became Umayyad staples. Many later historians, Abbasids as well as others seeking to justify the end of that glorious moment in Islamic history, would point disapprovingly to the way the Umayyads had absorbed and adapted the spolia and trappings of the civilizations they found as they spread throughout the world. To such purists, the open-hearted and eclectic syncretism of the Umayyads seemed a defect.

Page 829

A palm tree stands in the middle of Rusafa, Born in the West, far from the land of palms. I said to it: How like me you are, far away and in exile, In long separation from family and friends. You have sprung from soil in which you are a stranger; And I, like you, am far from home.

Page 875

Arabic became the language of Islam, permitting no other in which to be a Muslim, which meant, historically, that Arabic spread as rapidly and as far as the Islamic empire. It became the language of religion, and quite often a second or third language for those converts from the dozens of far-flung cultures, many of them ancient and already literate themselves, from the Pyrenees to the Chinese border.

Note: One of the many reasons the religion went viral

Page 895

The Christians love to read the poems and romances of the Arabs; they study the Arab theologians and philosophers, not to refute them but to form a correct and elegant Arabic. Where is the layman who now reads the Latin commentaries on the Holy Scriptures, or who studies the Gospels, prophets or apostles? Alas! All talented young Christians read and study with enthusiasm the Arab books; they gather immense libraries at great expense; they despise the Christian literature as unworthy of attention. They have forgotten their own language. For every one who can write a letter in Latin to a friend, there are a thousand who can express themselves in Arabic with elegance, and write better poems in this language than the Arabs themselves.

Page 917

There were also now many more mosques than churches, and the cathedral mosque, overflowing beyond capacity on Fridays, was being expanded once again. But Alvarus, whose allies in the resistance to the new religion were mostly the representatives of the embattled Church, knew that religion was only half the problem. The other half, directly laid out in those lines from The Unmistakable Sign, was that vast realm of culture intimately tied to faith and yet separate from it. The Muslims had brought to Hispania something that the half-crumbled Visigothic province could scarcely remember it had once had: a language that spoke with power and elegance about all the powerful human needs that lie outside a faith. Alvarus’s own words make the case unflinchingly: the Latin the young people were abandoning in droves was the tradition of commentaries on the Scriptures. But the Arabic they were embracing was not only that of prayer, but no less the one that had allowed Abd al-Rahman to write an ode to a palm tree to express his profound loneliness in exile, and which had since then been the language of a hundred years of love poetry—songs sung in Baghdad as well as in Cordoba. “They have forgotten their own language,” Alvarus plaintively remarks, because the Christians of Cordoba, like the Jews of Cordoba, had found in Arabic—not in Islam—something that clearly satisfied needs that the language of their own religion, Latin, had failed to meet. Arabic beckoned with its vigorous love of all the things men need to say and write and read that not only lie outside faith but may even contradict it—from philosophy to erotic love poetry and a hundred other things in between.

Page 949

In 855, a small number of the most radical opponents of the conversion of their Christian and Latin world openly sought martyrdom. One by one, they indulged in conspicuous public declarations of the deceits of Islam and the perfidies of the Prophet; and although Islam was elastic in matters of doctrine, particularly when it had to do with Christians, they had zero tolerance for disparagement of their Prophet. * The would-be martyrs thus knew for a certainty that they were forcing the hands of the authorities of the city by expressly choosing to vilify Muhammad. Leaders on both sides made every attempt to head off such radical behavior and its fatal consequences—in vain. The virulent public attacks continued and the offending Christians were beheaded in public. After about fifty of these gory executions, a spectacle that horrified and enthralled Cordobans of all religions, it was over. The passions of the moment passed and life went on as it had before in this city of thriving religious coexistence. The widespread civil unrest feared by both the Muslim and Christian hierarchies as the violent events were unfolding did not come to pass. But the young men and women who had provided this spectacle of self-immolation would not be forgotten: they were eventually transformed from a thorn in the side of a Church struggling to adapt and find its way in a complex, changing world, into the “Mozarab martyrs.” These fifty-odd Christians, incongruously and ironically remembered by the name that described their opposite, eventually became the near-sainted symbols of a cause that served the purposes of Christian chroniclers and analysts of later periods as an easy enough touchstone: brave Christians resisting the forced conversion “by the sword” that conventional history tells us was the way Islam spread, and suffering death for their heroism.

Note: Author is very certain about this characterisation. I can easily imagine these instances being spun a different way. In fact, it seems like that’s exactly what the church did.

I feel like this is also the kind of thing modern readers would be horrified at. No freedom of speech or religion. Shock!

Page 985

The dhimmi, as these covenanted peoples were called, were granted religious freedom, not forced to convert to Islam. They could continue to be Jews and Christians, and, as it turned out, they could share in much of Muslim social and economic life. In return for this freedom of religious conscience the Peoples of the Book (pagans had no such privilege) were required to pay a special tax—no Muslims paid taxes—and to observe a number of restrictive regulations: Christians and Jews were prohibited from attempting to proselytize Muslims, from building new places of worship, from displaying crosses or ringing bells. In sum, they were forbidden most public displays of their religious rituals. Not surprisingly, in any given historical case these relatively abstract and general provisions of the dhimma could and did materialize as either a genuinely tolerant and even liberating arrangement or, at the other extreme, a culturally repressive policy within which religious freedom is a hollow formality. The Umayyads, whose ethics and aesthetics were the very wellsprings of Andalusian culture, had more often than not been extraordinarily liberal in their vision of the dhimma, and their social policies were largely commensurate with their aesthetic vision, whose generous and absorbing attitudes about the past and about other cultures created the Great Mosque of Damascus—and that of Cordoba. Beyond the specific policy issues vis-à-vis the Peoples of the Book, the Muslims had transformed the cultural landscape in ways that were both inclusive and, by almost any measure, vast improvements over the half-ruined place they had found. Unlike the much resented Visigoths who preceded them, the Muslims did not remain a ruling people apart. Rather, their cultural openness and ethnic egalitarianism were vital parts of a general social and political ethos within which the dhimmi could and did thrive. As time passed, the perceived need to keep visible and distinct the Umayyad articulation of Islam, with its cultural eclecticism, became more pronounced, as the Abbasids and eventually other rivals for leadership in the House of Islam established their own competing political and cultural visions.

Note: So I picked up this book because I was looking for a history of alAndalus and the Maghreb. I found a thread on askHistorians specifically asking about whether alAndalus was tolerant towards Christians and Jews. The top answer said - here’s a book that says it was tolerant and another that says the opposite but both scholars leave a lot of room for nuance. Whereas the article OP was citing was very much lacking nuance. Separately, chatGPT also recommended this book.

My take is - on any historical question there’s more than enough material to make the case either way. If the question was scoped to a very specific time period like “between 2000 and 2023, was America good to minorities”, there’s no shortage of historical sources. You can write book length answers to that question from either perspective. The history of alAndalus on the other hand, is about 800 years of Arab, Berber and Christian rule. Fewer historical sources, much longer time period, impossible to answer in binary.

But there’s still enough material to make the case either way. You start with a stance, and then cherry pick a hundred incidents supporting that stance.

This is further complicated by people analysing historical incidents by modern standards. There’s no nuance. None of the societies in question were tolerant by the standards of the ideal, modern liberal democracy, so they’re all basically the same? Heck no.

Even incidents that should be straightforward like the execution of these Christian’s has nuance. They weren’t executed for professing their faith, they were executed for talking shit about others’ faith. Barbaric by modern standards, but enlightened by ancient standards.

Page 000

The positive consequences of newfound religious freedom and cultural openness on the Jewish community contrast with their effects on the Christians. As the Jews’ civic and political status improved dramatically within the Islamic polity, that of the Christians declined. From ruling majority the Christians had initially been demoted to being a majority governed by a minority of Muslims; from there, soon enough (and clearly by the time of Alvarus), their status had declined further, to the point where they were an ever-diminishing minority. Whereas Jewish ritual had long been, of necessity, a private and even domestic exercise, Christianity had long before expanded out of catacombs and house churches and into the public domain—and expected as a matter of course to exercise far more than mere freedom of conscience. Little wonder, given these differences, that the restriction on public displays of religion, while of small consequence to the Jews, had a seemingly catastrophic impact on the Christians. Most difficult of all to Christian partisans was the less analyzable matter of conversions, which certainly took place within the Jewish community but were fewer than those of Christians and did not adversely affect the community’s general size and well-being. By Alvarus’s time, a century after the establishment of the Umayyad polity, it would have seemed that Christians were abandoning the Church right and left. The majority Muslim community was growing, mainly thanks to the high rate of conversion. Most who remained Christian were content, eager even, to be Arabized—and thus Alvarus’s lamentation. Not only was his flock thinning rapidly, but the few loyal sheep that remained were so enamored of the wolf that they all wanted to dress in his clothing.

Note: This is a fantastic nuanced point. Even though the same restrictions existed on both Christians and Jews, it affected one community disproportionately.

No matter how you slice it, it sucks to go from being the majority to the minority. And it seems like there was not much change for the Jews but a massive change for the Christians. I can understand how that would have felt like persecution even if they were treated like equals (and it seems like they weren’t exactly, having to pay the jizya)

Page 032

But it was not just about Arabic. Latin, at this same time, was losing its hold everywhere. The language of Rome was itself disintegrating hundreds of years after the dismembering of its empire. No one in Cordoba at the time of Alvarus could possibly have known, but in 842, in the far-off city of Strasbourg, Latin suffered a blow at least as devastating as it was suffering at the hands of Cordobans who were abandoning it for Arabic. In that Frankish city, an official document was executed that recorded the mother tongues of Charlemagne’s various grandsons. The Oaths of Strasbourg, as we know this small but significant record, was the written version of a public oath of reconciliation and allegiance among the feuding brothers who had inherited Charlemagne’s domain. This was a kingdom that did not include any part of al-Andalus, as Charlemagne had once dreamt it might, but it was extensive nonetheless. The circumstances of the oaths are described in serviceable, boilerplate Latin. Then the document proceeds to transcribe faithfully what each said and swore out loud—this not in Latin but rather in the mother tongues of two of the three rival brothers, one Germanic, the other Romance.

Note: First I’m hearing of this Oath. Also, first I’m reading about the gradual phasing out of Latin.

Page 048

Yet the everyday “Latin” spoken in Paris was more than halfway to being as different from the “Latin” of Florence as French is from Italian today. And these still-unnamed mother tongues that were already “Romance,” the languages of the Romans’ children, were every day more different, not only from each other, but from unchanging Latin, which had become more a memory than a living thing.

Page 053

And Latin here, as elsewhere in the former western provinces of the Roman empire, had become largely ossified. That once vigorous instrument that had served Rome’s great poets, historians, and orators was now almost completely frozen in place. Those mother tongues, on the other hand, what people had been speaking for hundreds of years, had been changing inexorably, though still with little consciousness (and little need of such consciousness) of its being substantially different from what was written by everyone from the great Roman writers to the papal secretaries of the seventh century.

Page 082

The caliph had elevated Hasdai to higher and higher offices throughout his lifetime largely because Hasdai spoke and wrote with elegance and subtlety, and because the vizier possessed a profound knowledge of everything in Islamic and Andalusian culture and politics that a caliph needed in his public transactions. So it was that the prince of the Andalusian Jews had become the prestigious and powerful foreign secretary to the caliph. And this was no small-time, would-be caliph: during the lifetimes of Abd al-Rahman III and Hasdai, the Umayyad caliphate of Cordoba made its sweeping and plausible claim to absolute primacy within the House of Islam. Although for us it may seem astonishing that one of the most public faces of this Islamic polity, at its peak of power and achievement, should be a devout Jewish scholar, famously devoted to finding and aiding other Jewish communities in their scattered, worldwide exile, such suppleness was a natural part of the landscape of this time and place.

Page 150

Hasdai ibn Shaprut was born in Cordoba in 915 into a world brightly lit for Jews. In the previous 150 years of Umayyad rule, the Jews of al-Andalus had become visibly prosperous— materially, to be sure, and culturally even more so. To say they were thoroughly Arabized is to acknowledge that they did a great deal more than merely learn to speak the language of the rulers, something they no doubt did in the same several first generations, alongside Berber Muslims, Slavic slaves, and Visigothic converts. Under the dhimma brought by the Muslims, the Jews, who in Visigothic Hispania had been at the lowest end of the social and political spectrum, were automatically elevated to the covenanted status of People of the Book (alongside the Christians, for whom it was, instead, a demotion), which granted them religious freedom and thus the ability to participate freely in all aspects of civic life.

Page 179

The Jews understood themselves to be Andalusians and Cordobans, much as the German Jews of the late-nineteenth century—Marx and Freud most prominent among them—considered themselves Germans, or the American Jews in the second half of the twentieth century, who helped define the intellectual and literary qualities of their time, never thought twice about calling themselves Americans. But unlike many later European and American Jews, the Andalusian Jews had not had to abandon their orthodoxy to be fully a part of the body politic and culture of their place and time. The Jews of al-Andalus were able to openly observe and eventually enrich their Judaic and Hebrew heritage and at the same time fully participate in the general cultural and intellectual scene. They could be the Cardozas and the Trillins and the Salks of their times because they were citizens of a religious polity—or rather, of this particular religious polity. The Umayyads, much like the Abbasids who devoted vast resources and talent to the translation of Greek philosophical and scientific texts, had created a universe of Muslims where piety and observance were not seen as inimical to an intellectual and “secular” life and society.

Page 318

Those last years, however, especially those of al-Mansur’s colorful life and politically momentous reign, overflowed with fateful and future-shaping events. The armies of mercenaries al-Mansur brought into al-Andalus from North Africa became, as the years went by, more and more like foreign policemen, with little understanding and less love for the Andalusians. Themselves strangers in a strange land, these Berbers were increasingly resented by the Cordobans. But for al-Mansur they were a necessary part of his relentless and exhausting military campaigns against the Christian territories to the north, campaigns that under his leadership acquired a fanatical and ideological pitch scarcely seen before. Al-Mansur even acceded to the request of some that al-Hakam II’s library be purged, and he was said to carry with him while on campaign a Quran he had copied with his own hand.

Note: The author persistently paints the Arabs as the broad minded, cosmopolitan good guys whereas the Berbers are the backward, regressive, violent dudes smashing beautiful things, repressing everyone else.

Page 325

In 997, al-Mansur led an unprecedentedly destructive raid into Santiago de Compostela, the site of a local cult to the apostle James, whose bones had purportedly been found there in the ninth century. The vicious burning of the city, and. the carting away of all the church bells back to Cordoba to be used as mosque lamps, helped catapult Santiago from local to near mythological importance in the subsequent century. The city became the very symbol of Christianity on the peninsula and a legendary pilgrimage site of international proportions, both of which remain largely true today. James himself was eventually transformed from mere apostle of Jesus to the patron saint of what would eventually be called the “Reconquest,” and his name enhanced by the epithet Matamoros, or “the Moor-slayer.” The bells for which so high a price was thus paid—and this gratuitous taking of purely religious trophies was rightly perceived as a very different matter from territorial expansion or defense—were carried back to a Great Mosque that al-Mansur had himself expanded just a few years after al-Hakam’s expansion. These latest and proportionally overwhelming enlargements were done at least in part to accommodate the considerable new population of Berbers that al-Mansur had been importing to Cordoba.

Page 749

These songs reflected explicitly the complex and hybrid identity that had been the self-conscious hallmark of the Andalusians from the time of Abd al-Rahman I. The ring song (in Arabic it is called muwashshaha, from the word for “sash,” “circle,” or “girdle”) broke all the rules of the classical Arabic poem that had come out of the desert and been cultivated lovingly and carefully in Baghdad and everywhere else among the Arabic-speaking peoples. Where the poetry of the old world had a single rhyme linking all the verses, whether five or five hundred, the ring song did quite otherwise. As its name suggested, this kind of song made rhyme an encircling device, repeating rhyme patterns of sometimes dizzying complexity, with internal rhymes as well as those linking one stanza to another. The stanzas themselves were a new thing, also a part of the insurrection of the vernaculars of the time. The courtly performance of the traditional Arabic lyric had no need for stanzas, for breaks between one thought in the song and the next. On the contrary, its specific aesthetic called for seamlessness, a single continuous strand of lyrical expression whose outward form is in part marked by the single rhyme sound and in part by the absence of distinct regular breaks. This new song form was different: this was dance music that had come in off the streets. The song was broken into stanzas that were then “ringed” with the most astonishing part of all, a simple little refrain to be repeated after each of the stanzas, much as in any modern song of ours. These simple few lines turned the whole tradition upside down because they were so impudently unclassical. The main stanzas of the song were still in classical Arabic, although now sung to the beats and rhymes of the little refrain. But the voice in the refrain was that of a woman, and she was singing in the vernacular. Beyond that, in terms of content, the refrain almost always upset the expectations and intentions of the rest of the song: whereas the classical voice sings of love with the usual high-flown metaphors and allusions, the vernacular voice replies with a curt “shut up and kiss me.” In these new songs, the mother tongues thus literally run rings around the classical poets and their fine language: in their kitchen Arabic or in that tattered Latin spoken by the Mozarabs that was consanguinous to langue d’oc, these final lines were the key to the Andalusian proclamation of cultural ascendance and uniqueness, no less than the horseshoe arches in the Great Mosque.

Note: I’ll be honest. I’ve never been able to appreciate poetry. Defect In my brain perhaps. This isn’t terribly interesting to read for me.

Page 871

In 1066, ferocious anti-Jewish riots broke out in Granada. Among the many victims was Joseph, the son of the city’s much loved vizier; Joseph, the editor of his father’s earthshaking poems in the new Hebrew of the age; Joseph, who had laid out the gardens at the top of the fortified hill, next to the old Red Fortress. There are, as always, conflicting accounts and interpretations of the causes of this relatively isolated Muslim uprising against what had been a warmly favored Jewish community. The taifas were notorious for precisely the sort of intimacy with Christians and Jews that both Joseph and Ferdinand represented, the first as the powerful and prestigious heir to his father, the latter as a close and reliable ally whose help allowed the retaking of Barbastro from the Normans. All of this seemed normal to the Andalusians, who were heirs to the Umayyad interpretation of the dhimma and who now lived in cultural circumstances where Muslims were even more rarely isolated from Christian and Jewish communities than they had been during the caliphate. But the ages-long Andalusian forging of political and cultural accommodations with Jews and Christians was interpreted as a lax or even heterodox view of Islamic law by the more purist Berber Muslims of North Africa, who had already wreaked havoc in the last days of the caliphate and who were seemingly always aware of what was going on just across the Strait of Gibraltar. Not too many years down the road—the same road that takes us to that church in Toledo—these nearly irreconcilable differences would loom very large.

Note: Author goes to great pains to say this is an isolated incident, usually everyone gets along, and as usual the Berbers are at fault. Although curiously, they’re not very explicit about that.

Page 908

Sancho of Leon, Ferdinand I’s oldest son, was not the only principal player to die of foul play in these closely intertwined tales. Just a few years after the drama at Toledo and Zamora, in 1075, while Alfonso was just managing to consolidate his territories of Castile and Leon, the great al-Mamun of Toledo, who had not so long before protected Alfonso from his own brother, also fell victim to treachery and political assassination. Al-Mamun had ruled Toledo for thirty-three years and made it the cultural showplace of the peninsula. At the time of his murder he had recently succeeded in the military mission that would also have made Toledo politically preeminent among the taifas and perhaps unified them, which was certainly al-Mamun’s ambition: after a lifetime’s effort, al-Mamun had taken the coveted city of Cordoba from his archrivals in Seville. But beneath the superficial similarity of the kings’ murders—the Christian king of Leon and the Muslim king of Toledo—the two situations could not have produced more different outcomes. Whereas Sancho’s death led the various kingdoms over which he and his brothers had feuded out of fratricidal violence and civil wars and into Alfonso’s long, prosperous, and unifying reign, the death of al-Mamun, who had powerfully and profitably guided Toledo to a position of stability and expansiveness, resulted in a series of catastrophically weak and rivalrous successors and a period of bloody civil unrest in Toledo. The possibility that a single taifa might emerge as a unifying leader of al-Andalus was lost.

Note: Most of this is just luck or coincidence.

Page 940

the siege did not last long, and in the spring of 1085, with not a drop of blood shed in battle, Alfonso VI of Castile and Leon entered venerable Toledo, a city he already knew and loved, a city that al-Mamun had spent more than thirty years grooming to be the successor to Cordoba itself. In all sorts of ways, that was exactly what it became, but with the remarkable twist that Alfonso and his successors were Christians, not Muslims. Yet they were the Christians whose descendants, as late as a century or more later, would build the Church of San Roman, with the horseshoe arches that pay loving homage to Cordoba itself, and who would keep other aspects of Cordoba’s legacy alive and well.

Page 963

The Andalusian Muslims, the old taifas, were momentarily relieved and returned to their squabbling ways, but not for very long. The Almoravids, once they had gotten a close look at the Andalusians, were filled with contempt for their obvious military ineptness and chaotic politics. At the same time, they appeared seduced, and full of the sort of greedy desire for the still-palpable delights of al-Andalus that had so affected Alfonso. Within a few years of defeating Alfonso and returning to their lands across the strait, the Almoravids came back with the clear intention of staying and making al-Andalus a province, the jewel in the crown of an empire that began on the banks of the Senegal River in Africa. By that time the Andalusians had gotten as much of a taste as they wanted of the rough Berbers from beyond the Atlas Mountains, barbarians by Andalusian standards. Most of the taifa kings had concluded that Alfonso himself would be a more congenial overlord than those stiff-necked, morally self-righteous, and culturally backward Muslims, and al-Mutamid, the poet-king of Seville, and others ended up appealing to Alfonso for help in opposing the very Muslims they had originally brought in to protect themselves against him. But it was too late. Within a few years, the Almoravids made the shredded remnants of al-Andalus, the remaining taifas, their unhappy colony, while also attempting a radical reform of the Muslim ways of the peninsula.

Page 048

it is believed he ended up making his fame, and perhaps fortune, as something of a wise man in the land he first chose for his exile, England. He was probably among the retinue of physicians attending Henry I, the son of William the Conqueror, who ascended the English throne in 1100. This was an altogether likely role for a man like Petrus, since an educated “physician” at that time was expected to be well versed in natural philosophy, a field of learning that was relatively commonplace for a Jew of even middling education in late eleventh-century Spain. Although the details of his early years are uncertain, he had been born and reared somewhere in Islamic Spain, perhaps in the south, before he emigrated to the still-Muslim, still-independent northern cities, as did many others in the chaos of the last years of the taifas. Whatever his exact peregrinations before settling in Huesca, he had managed to receive, beyond his religious training in Hebrew, the conventional Arabic education in the sciences, philosophy, and rhetoric. Regardless of why he left his homeland, Petrus discovered on the far northern side of the Pyrenees, in Norman England and later back on the continent, possibly in Normandy, that he was a celebrity sage. This new-fashioned Christian with the freshly minted Latin name had a level of learning that, customary as it might have been in the Jewish-Muslim circles of educated Andalusians, was astonishing in the far northern climes of Europe in the early years of the twelfth century. It represented knowledge of a forgotten past, of wisdoms that were deeply buried there, while at the same time it suggested a hard-to-believe future. Petrus became a widely read author on high-tech subjects that were just beginning to be apprehended and coveted outside the Arabic-reading world: astronomical tables, astrology, calendrical calculations, astrolabes. His mind was far from first class in these matters, however, and his scientific work would eventually be supplanted by the next generation of scientists and philosophers—other émigrés from the peninsula, but especially northerners who would go to places like Toledo to study.

Note: Author tries to portray this guy as middling, and by extension the Northerners who exalted him as a genius. All this to make it clear that the centre of all learning was alAndalus. I wouldn’t be surprised if this thesis was overstated and the Northerners weren’t completely ignorant bumpkins.

Page 070

Petrus Alfonsi (or “Piers Alphonse,” as Chaucer called him) stands out as a scientific pioneer and benefactor: he had brought news of a new intellectual universe from the Arabophone Mediterranean and, having whet the appetite, he had shown the way to satisfy it. He had become, in effect, England’s first professor of Arabic, which meant a teacher not of the technical aspects of the language itself. Rather, Petrus was one of the first native teachers of the aesthetic and intellectual culture he had known in the places he had left behind, a land of libraries full of books, libraries scarcely imaginable in his new home.

Note: It occurs to me, it’s probably much harder to maintain a library in cold and damp England.

Page 113

In Petrus’s Priestly Tales, the elite Latin-reading world got its first real taste of a feast that in al-Andalus was available to nearly everyone on an everyday basis, and that tied al-Andalus to the rest of the Islamic empire. Even the humblest Andalusian Christian, because he could understand spoken Arabic, or because his neighbor could and retold stories in his Aragonese vernacular, was able to hear tales that had once been told in Greek or Persian and now were being retold in Arabic, and a thousand and one permutations, from one end of the empire to the other, by the master storyteller herself, Scheherazade.

Note: Is that 1001 nights?

Page 230

Halevi was the last in the line of great Andalusian poets of the Golden Age, as it was dubbed by the nineteenth-century German Jews who became their historians and editors, men who saw in those urbane, philosophically mature, and socially successful Jews of the eleventh and twelfth centuries a winning reflection of what they wished the European Jews of the nineteenth to be. The golden Andalusian line that ended far from al-Andalus— symbolically trampled underfoot at the gates of Jerusalem—had begun with the self-styled David of his age, Samuel the Nagid; it was the line that had made writing in Hebrew a living thing once again, so that Halevi’s love songs to Jerusalem were not part of the fossilized liturgical Hebrew that was all Jews could chant before these Andalusians had come along.

Note: If it’s true the Jews later considered this a golden age, that’s important.

Page 244

Hebrew’s redemption had come at the hands of writers who were masters of Arabic rhetoric, the Andalusian Jews, men as thoroughly and successfully a part of the cult of Arabic grammar, rhetoric, and style as any of their Muslim neighbors and associates. A century before Halevi took his final leave to find Jerusalem, Samuel the Nagid had first made Hebrew perform all the magic tricks that his native tongue, Arabic, could and did. He had been made vizier because his skill in writing letters and court documents in Arabic surpassed that of all others. He then went on to write poems in the new Hebrew style, among them verses recounting his glories leading his taifa’s armies to victory. In one fell swoop, Samuel’s Hebrew poetry, with its Arabic accents and prosody—the features essential to making it alive for the Arabic-speaking Andalusian Jews—vindicated and completely exceeded all the small steps that others had taken in the centuries before him to revive the ancestral language, to reinvent it as a living tongue. Everyone, from Halevi to the nineteenth-century Germans who made the Andalusians into the noble heroes of Jewish history, knew that Hebrew had been redeemed from its exile thanks to the Andalusian Jews’ extraordinary secular successes, first during the several Umayyad centuries and then in the taifas. Because they had absorbed, mastered, and loved the principles that made Arabic easily able to sing to God and Beloved in the same language, they had been able to revive Hebrew so it could, once again, sing like the Hebrew of David’s songs, and Solomon’s songs. It was a great triumph, and Judah Halevi was arguably its greatest champion.

Page 263

Almoravid rule was making life for many Jews more difficult, and many even had to emigrate to the north, once considered a land of savages; but at the same time, some Christian cities, among them the Castilian capital, Toledo, were becoming thriving centers of Jewish life. There was in any case a vast difference between the vicissitudes of modern life, with the tyranny of the detested foreign Muslims, and the old and fruitful traditions that had made the Andalusian Jews the very center of the Jewish universe in the post-exilic period. Yet what Halevi was attacking was not the difficult political moment but the very bases of the Jews’ culture, the love of Arabized Hebrew poetry that Halevi himself had developed with such moving beauty, along with the study of philosophy, which Halevi began to call, contemptuously, “the Greek religion.” Halevi was saying that all men of True Faith should, as he was going to do, exile themselves from everything Andalusian, from al-Andalus itself. That, for most of his contemporaries, was the threat of a truly terrible exile.

Page 340

Just as Petrus Alfonsi’s Dialogue was an argument between two versions of the author’s own self, pre- and post-conversion, Halevi’s Book of the Khazars is about the different ways of living as a Jew, which he takes the rabbi and the philosopher to represent. Its central question—whether faith and reason can be held simultaneously or are inherently contradictory, to put it reductively—would soon emerge as one of the great debates of the age and would occupy many great thinkers of all three of these monotheistic traditions. Indeed, in nearby Cordoba, the two most brilliant and subtle writers on this thorny question in the twelfth century were at present being educated much as Halevi had been. In 1140, Ibn Rushd, who would later be known mostly by the Latin name Averroes and as the author of the great commentaries on Aristotle, was already fifteen, and Musa ibn Maymun, who as Maimonides would be revered as the “second Moses,” was five years old. Neither would give much credence to Halevi’s conventionally pietistic rejection of the strong philosophical tradition the Jews had participated in along with the Muslims—what Halevi dismissed as “the flaunted Greek wisdom whose end is folly, seems to enlighten but leaves desolation.” Halevi’s turn was by no means simplistic or one-dimensional like Petrus Alfonsi’s; it was not, for example, a turning away from philosophy to religion, or from rationalism to faith, from unbeliever to believer. Instead, Halevi was rejecting— and this was precisely what his own community found so inexplicable — the very premise of the commensura bility of the two, philosophy and religion. The bedrock of Andalusian Jewish culture for hundreds of years, what had allowed it to flourish in the ways it had, was the premise that genuine Jewish culture and devout faith in Judaism were not at destructive odds with the whole complex of secular activities they had been cultivating, neatly represented by both Greco-Islamic philosophy and the unabashedly Arabized new Hebrew poetry. This community did not imagine it had bought its secular and cultural success by renouncing, hiding, or in any way diminishing its Jewishness. On the contrary, against Halevi were those who argued that the Andalusian Jews’ radical degree of cultural assimilation had allowed them to become more fully Hebraized than any Jewish community had been for a thousand years, and thus far more profoundly in touch with their heritage as Jews. Although of course no one in The Book of the Khazars makes this argument directly, the case is made most brilliantly by Halevi’s own extraordinary corpus of some eight hundred poems, among which are his gorgeous love songs to Jerusalem and Zion, songs that come directly out of the same poetic traditions and complex Arabized culture he now rejected.

Note: What was his issue really? Was it that they adopted a “foreign” language or that they searched for truth outside of scripture? The two problems are linked, because philosophy was written in Arabic, but it’d be interesting to know which he had a bigger problem with.

Also, it would be good to get the perspective of someone who rejected reason in favour of faith. It’s such a bizarre decision to my way of thinking that it would broaden my mind to understand it.

Page 376

The poem depicts this as the singularly undeserved exile of the loyal hero Rodrigo, and one of the poem’s loveliest and best-known lines follows soon after this scene—when the good citizens of Burgos, the city to which the Cid first travels in his exile, cry out, “Dios, que buen vasallo, si oviesse buen señore” (“God, how fine a vassal, if his lord were but worthy”).

Page 387

By 1094, the Cid had acquired enough wealth and military strength, through campaigns like those against Alfonso’s lands, to mount a successful assault on Valencia—an event depicted in the poem in somewhat different terms, with the loyal Cid taking the city for his king Alfonso. As the self-declared king of that lovely city by the sea, Rodrigo had to defend himself from attacks from all sides, but especially from the ever encroaching Almoravids, who were almost done removing the Muslim taifa kings from power and were certainly not going to suffer a renegade Christian holding a major port on the peninsula’s eastern coast. Yet the great warrior was never defeated by them, although Valencia was, in 1102. Rodrigo had died, apparently in his bed and of natural causes, in 1099, the same year that the first Latin Crusaders took Jerusalem, exemplars of a new ideological age, a narrow political culture far removed from anything the Arabic-speaking Cid would have understood.

Note: This is the point the author repeatedly drives home in this book. Religion and conquest alone give only a partial picture of this region and era. The lens of Culture, especially language and poetry plays a massive role in helping us understand better.

El Cid was not the same as the crusaders simply because he was a Christian who fought Muslims. The author says him speaking Arabic says more about him.

It’s telling that the early Crusades didn’t find much purchase in alAndalus.

Page 408

But as with the story of Halevi’s life and the culture he is said to represent, these proto-nationalist stories are to be taken not only with the customary grain of salt but with considerable irony. The Cid was infinitely more complex—for better and worse—than the loyal vassal to a not-quite worthy sovereign, and the dizzyingly complex political circumstances of his moment were such that simple loyalties—for better and worse— were rarely to be found. It is not only the Cid but the Castilian monarch himself who is at times the enemy and at times the indispensable ally of the Andalusian Muslims of any given taifa.

Page 503

In Toledo especially, where the large and influential Mozarabic community felt it had been the privileged guardian of the oldest preserved rite in Christendom, there was resistance to these newfangled changes, and to the foreign domination that had imposed it. From the ninth through the eleventh centuries, the Mozarabs had preserved their own way of celebrating the Eucharist, not in Latin, the liturgical language of Western Christendom, but in Arabic. In this cultural and linguistic isolation from other changes in Latin Christendom, the rite thus survived in its most conservative form—but after 1085, its survival was threatened by the Cluniac reform of the liturgy, which sought to universalize the practices of Western Christendom. The tensions between the two groups of Christians there, Mozarabs and “Romans,” would last for hundreds of years and may be broadly understood as symbolic of the conflict between a special indigenous tradition and the foreign-born impositions that were required if Spanish Christians were to be fully integrated with the rest of the Catholic community.

Note: Why do people get so dogmatic about this. Maybe because the most dogmatic types end up in the clergy?

Page 577

And yet, while for Abelard, Seneca was still the master philosopher he actually knew, already Petrus Alfonsi, another contemporary, was condescending to pass on to the clerics of Europe the bits and pieces—“as the Arab philosopher says”—of his perfectly conventional Andalusian education, and he would doubtless have found the notion of Seneca as a master philosopher risible. It would have amused Robert of Ketton as well, who at the time of Abelard’s death was sitting amid the golden horde of hard science and Aristotelian splendor beginning to pour out of Toledo.

Note: Typo - hoard, not horde.

Page 626

But Peter’s provocations did not stop there: he was sending these materials to Bernard so that Bernard himself would be able to write the great refutation of Islam that surely undergirded his militant posture abroad. Not surprisingly, Bernard never did any such thing, and when Peter himself got around to writing his version of the analysis of the superiority of Christianity to Islam, on the basis of his reading of the Quran as well as the other materials he had gathered, he began with the lament that the task had fallen to him, since no other Christian had come forth to undertake it: “There was not one who would open his mouth and speak up with zeal for Christianity.” The tone, in this context, was something like mock regret, or even slightly veiled sarcasm, directed at Bernard, whose brand of zeal Peter certainly did not endorse.

Note: Funny guy 😅

Page 720

The translation of texts into Latin from Arabic became a vigorous enterprise just as the Muslim dominions in the Iberian Peninsula diminished. Citizens under the Umayyads—Muslims, Jews, even Christians—were not proselytizers of their own culture, or of the Greek philosophical culture that became their own over the years; they had no reason to care whether the libraries of texts they read and worked with were available to those who could not read Arabic. Until the eleventh century and the large-scale movements of peoples across borders that followed the breakup of the caliphate and the subsequent reign of the taifas, there was little knowledge in the Latin Christian world, on either side of the Pyrenees, of what might even be in those libraries, and even less in the way of resources to comprehend their contents. Some important translations did appear before the end of the eleventh century, but they were few and far between. The situation began to change as Christians from the north moved farther into the south and came directly into contact with the libraries. At the same time, many of the new citizens of the expanding Christian realms were individuals who could make those storehouses of knowledge available to the new rulers. When Alfonso VI took over Toledo in 1085, he simultaneously acquired an immense wealth of books and, the greatest gift of all, whole communities of multilingual Toledans—Mozarabs and Jews prominent among them—who could serve as translators. At the turn of the twelfth century, the hunger for translations was felt even farther afield, and for many reasons. The Latin Christian communities had become increasingly aware of the technological and philosophical riches in the Arabic libraries. That awareness was often aroused by the expansion of monastic centers, Cluny foremost among them, in the newly opened territories farther south of the Pyrenees. The irony, then, was that the intellectual influence of Arabic-based learning and culture—in part Muslim, in part Greek (the latter transmitted via Baghdad in Arabic translations and with Arabic commentaries)—waxed in almost direct proportion to the political waning of what remained of al-Andalus.

Note: Last line is fascinating. It’s possible that if alAndalus hadn’t faded, there would have been no opportunity or expertise to translate all of these works to Latin.

I sometimes think of historical what-ifs. It’s hard to consider second and third order effects of those changes. Like Alphonso VI slips and falls and suddenly the Enlightenment is strangled before it was born because they didn’t receive this vital knowledge from all of this translation.

Page 746

In the aftermath of Alfonso’s takeover of Toledo in 1085, the Almoravids had become harsh colonizers of the Andalusians, who chafed both at their loss of independence and at the inimical version of Islam the Almoravids had imported and imposed on them. The Andalusians were never successful in any of their anti-Almoravid uprisings—not even those in alliance with their Christian neighbors, beginning with Alfonso VI himself, the very sovereign whose expansions they had sought to check with Almoravid aid. But the Almoravids eventually suffered an overthrow back in their own North African centers at the hands of another, even more repressive, Berber regime, that of the Almohads, which ended the Almoravid reign in al-Andalus after little more than fifty unstable years. The new regime was measurably worse: these Islamic fundamentalists imposed dramatic changes on their Andalusian province, none perhaps more transforming than the immediate expulsion of Jews from many of the Andalusian cities. The fallout from this expatriation of a central part of the Andalusian community was widespread; in one sense, it amounted to a paradoxical series of gifts to other parts of the Muslim world, as well as to the Christian kingdoms to the north. In the northern Christian cities, many of which had not long before been taifas, and before that cities of the caliphate, Jewish immigrants found a society where they were not alone in their Arabized ways, and where they were able to prosper, at least in part because of their familiarity with Muslim culture.

Page 764

The Arabized Jews who under Almohad pressure began to resettle in Christian territories became an important link, along with the Mudejars, to the old Andalusian universe, to its continuation as well as to its transmission. It was at this time that the translation of thousands of Arabic volumes into Latin began in earnest, and within fifty years, Latin readers throughout Christendom had at their disposal such once-unimagined wonders as the full body of Aristotle’s works, accompanied by extensive Muslim and Jewish commentaries as well as other study aids, both ancient and contemporary. In sharp contrast to what Peter the Venerable had found, a man like Michael Scot could go to Toledo at the turn of the thirteenth century and find not only skilled translators but a whole culture of translation. Michael and many others went to Toledo to learn Arabic and to train in the special process of collaborative translation developed there. The common model was for a Jew to translate the Arabic text aloud into the shared Romance vernacular, Castilian, whereupon a Christian would take that oral version and write it out in Latin. Beyond technique, however, what Michael Scot and his contemporaries carried away from that richly polymorphic Toledo during those years was a zeal for unpacking and translating not just texts but the Andalusian culture that lay behind them. The translators of the Toledo “school,” then, were translating more than individual texts—they were translating a culture. Christian translators were also increasingly aware that the books they were working on, even when they were Arabic translations of original Greek texts, were by then bearers of Andalusian culture, and, inevitably, bearers of the Arabic culture centered in Baghdad. Translation itself, as well as the texts being translated, played a vital role for the hundreds of years during which the Muslims had thought the rational sciences and philosophy indispensable to their libraries. And it was that culture of translation, perforce a culture of tolerance, that was now captivating Latin Christendom.

Page 778

At the same time, the Almohad-controlled cities and regions of the old al-Andalus began to lose some of what had made them distinctive, as their ancient Jewish and Christian populations departed into exile, and as their narrow interpretation of Islam made their scholars far less avid than many Latin readers of that scientific and philosophical library, the memory palace of the Abbasids and the Umayyads. Perhaps the most negative effect of Almohad ideology and its practice in Spain was the harshness embodied in the Almohads’ stridently monolingual, purist Muslim regime. It went a long way toward creating a climate of true Muslim-Christian enmity, something that had been, until then, quite secondary to other forms of hostility and competition. The political instability and disunity created by this clash of Muslim ideals and styles coincided with the extraordinarily heightened papal power and influence of Innocent III during his years as pontiff, 1198 to 1216. In 1212, with Innocent’s encouragement and support, and with the provocations provided by the Almohads’ heightened hostility, the diverse and fractious Christians of Spain joined with troops from the north to march against the Muslims, and they routed the Almohads. The battle that took place in 1212 in Las Navas de Tolosa, just south of the Sierra Morena, the range that lies between the two old rival capitals of Toledo and Cordoba, marked the beginning of the last days in the disastrous Almohad chapter, sixty-four years after it had begun. An almost unremitting series of Muslim losses and retreats followed that turning point, as one city after another fell to the armies led by Ferdinand III of Castile.

Note: Author hasn’t said a single redeeming thing about the Almoravid or Almohads. These dudes are basically the ISIS of the 12th century.

Page 843