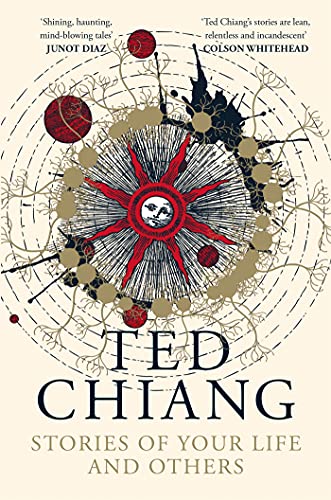

Stories of Your Life and Others

by Ted Chiang

- Author:

- Ted Chiang

- Status:

- Done

- Format:

- eBook

- Genres:

- Short Stories , Science Fiction , Fiction , Fantasy , Book Club , Speculative Fiction , Science Fiction Fantasy

- Pages:

- 338

- Highlights:

- 15

Highlights

Page 214

After dinner, he asked Kudda and his family, ‘Have any of you ever visited Babylon?’ Kudda’s wife, Alitum, answered, ‘No, why would we? It’s a long climb, and we have all we need here.’ ‘You have no desire to actually walk on the earth?’ Kudda shrugged. ‘We live on the road to heaven; all the work that we do is to extend it further. When we leave the tower, we will take the upward ramp, not the downward.’

Page 233

Then they approached the sun. It was the summer season, when the sun appears nearly overhead from Babylon, making it pass close by the tower at this height. No families lived in this section of the tower, nor were there any balconies, since the heat was enough to roast barley. The mortar between the tower’s bricks was no longer bitumen, which would have softened and flowed, but clay, which had been virtually baked by the heat. As protection against the day temperatures, the pillars had been widened until they formed a nearly continuous wall, enclosing the ramp into a tunnel with only narrow slots admitting the whistling wind and blades of golden light.

Note: Fascinating. He’s really leaning into this biblical narrative.

Page 449

Somehow, the vault of heaven lay beneath the earth. It was as if they lay against each other, though they were separated by many leagues. How could that be? How could such distant places touch? Hillalum’s head hurt trying to think about it. And then it came to him: a seal cylinder. When rolled upon a tablet of soft clay, the carved cylinder left an imprint that formed a picture. Two figures might appear at opposite ends of the tablet, though they stood side by side on the surface of the cylinder. All the world was as such a cylinder. Men imagined heaven and earth as being at the ends of a tablet, with sky and stars stretched between; yet the world was wrapped around in some fantastic way so that heaven and earth touched. It was clear now why Yahweh had not struck down the tower, had not punished men for wishing to reach beyond the bounds set for them: for the longest journey would merely return them to the place whence they’d come. Centuries of their labor would not reveal to them any more of Creation than they already knew. Yet through their endeavor, men would glimpse the unimaginable artistry of Yahweh’s work, in seeing how ingeniously the world had been constructed. By this construction, Yahweh’s work was indicated, and Yahweh’s work was concealed. Thus would men know their place. Hillalum rose to his feet, his legs unsteady from awe, and sought out the caravan drivers. He would go back to Babylon. Perhaps he would see Lugatum again. He would send word to those on the tower. He would tell them about the shape of the world.

Note: Excellent ending. I was expecting the biblical intervention.

Page 721

I must admit that, while penetrating computer security remains generally unaesthetic, certain aspects of it are indirectly related to very interesting problems in mathematics. For example, a commonly used method of encryption normally requires years of supercomputer time to break. However, during one of my forays into number theory, I found a lovely technique for factoring extremely large numbers. With this technique, a supercomputer could break this encryption scheme in a matter of hours.

Note: Only computer science kids will appreciate this humongous flex

Page 761

Having realized this, however, I won’t build such a device, or any other. It would require many custom-built components, all difficult and time-consuming to procure. Furthermore, actually constructing the device wouldn’t give me any particular satisfaction, since I already know it would work, and it wouldn’t illuminate any new gestalts.

Note: Like the solution to Fermat’s Last Theorem

Page 414

Your father is about to ask me the question. This is the most important moment in our lives, and I want to pay attention, note every detail. Your dad and I have just come back from an evening out, dinner and a show; it’s after midnight. We came out onto the patio to look at the full moon; then I told your dad I wanted to dance, so he humors me and now we’re slow dancing, a pair of thirty-somethings swaying back and forth in the moonlight like kids. I don’t feel the night chill at all. And then your dad says, ‘Do you want to make a baby?’

Note: I love this scene. The music. I’m glad the movie stayed true to this.

Page 962

A twinkle appeared in Gary’s eyes. ‘I’ll bet I know what you’re talking about.’ He snipped a potsticker in half with his chopsticks. ‘You’re used to thinking of refraction in terms of cause and effect: reaching the water’s surface is the cause, and the change in direction is the effect. But Fermat’s principle sounds weird because it describes light’s behavior in goal-oriented terms. It sounds like a commandment to a light beam: “Thou shalt minimize or maximize the time taken to reach thy destination.”’ I considered it. ‘Go on.’ ‘It’s an old question in the philosophy of physics. People have been talking about it since Fermat first formulated it in the 1600s; Planck wrote volumes about it. The thing is, while the common formulation of physical laws is causal, a variational principle like Fermat’s is purposive, almost teleological.’ ‘Hmm, that’s an interesting way to put it. Let me think about that for a minute.’ I pulled out a felt-tip pen and, on my paper napkin, drew a copy of the diagram that Gary had drawn on my blackboard. ‘Okay,’ I said, thinking aloud, ‘so let’s say the goal of a ray of light is to take the fastest path. How does the light go about doing that?’ ‘Well, if I can speak anthropomorphic-projectionally, the light has to examine the possible paths and compute how long each one would take.’ He plucked the last potsticker from the serving dish. ‘And to do that,’ I continued, ‘the ray of light has to know just where its destination is. If the destination were somewhere else, the fastest path would be different.’ Gary nodded again. ‘That’s right; the notion of a “fastest path” is meaningless unless there’s a destination specified. And computing how long a given path takes also requires information about what lies along that path, like where the water’s surface is.’ I kept staring at the diagram on the napkin. ‘And the light ray has to know all that ahead of time, before it starts moving, right?’ ‘So to speak,’ said Gary. ‘The light can’t start traveling in any old direction and make course corrections later on, because the path resulting from such behavior wouldn’t be the fastest possible one. The light has to do all its computations at the very beginning.’ I thought to myself, the ray of light has to know where it will ultimately end up before it can choose the direction to begin moving in. I knew what that reminded me of. I looked up at Gary. ‘That’s what was bugging me.’

Page 072

I liked to imagine the objection as a Borgesian fabulation: consider a person standing before the Book of Ages, the chronicle that records every event, past and future. Even though the text has been photoreduced from the full-sized edition, the volume is enormous. With magnifier in hand, she flips through the tissue-thin leaves until she locates the story of her life. She finds the passage that describes her flipping through the Book of Ages, and she skips to the next column, where it details what she’ll be doing later in the day: acting on information she’s read in the Book, she’ll bet $100 on the racehorse Devil May Care and win twenty times that much. The thought of doing just that had crossed her mind, but being a contrary sort, she now resolves to refrain from betting on the ponies altogether. There’s the rub. The Book of Ages cannot be wrong; this scenario is based on the premise that a person is given knowledge of the actual future, not of some possible future. If this were Greek myth, circumstances would conspire to make her enact her fate despite her best efforts, but prophecies in myth are notoriously vague; the Book of Ages is quite specific, and there’s no way she can be forced to bet on a racehorse in the manner specified. The result is a contradiction: the Book of Ages must be right, by definition; yet no matter what the Book says she’ll do, she can choose to do otherwise. How can these two facts be reconciled? They can’t be, was the common answer. A volume like the Book of Ages is a logical impossibility, for the precise reason that its existence would result in the above contradiction. Or, to be generous, some might say that the Book of Ages could exist, as long as it wasn’t accessible to readers: that volume is housed in a special collection, and no one has viewing privileges. The existence of free will meant that we couldn’t know the future. And we knew free will existed because we had direct experience of it. Volition was an intrinsic part of consciousness. Or was it? What if the experience of knowing the future changed a person? What if it evoked a sense of urgency, a sense of obligation to act precisely as she knew she would?

Note: Free will.

Page 113

Consider the phenomenon of light hitting water at one angle, and traveling through it at a different angle. Explain it by saying that a difference in the index of refraction caused the light to change direction, and one saw the world as humans saw it. Explain it by saying that light minimized the time needed to travel to its destination, and one saw the world as the heptapods saw it. Two very different interpretations. The physical universe was a language with a perfectly ambiguous grammar. Every physical event was an utterance that could be parsed in two entirely different ways, one causal and the other teleological, both valid, neither one disqualifiable no matter how much context was available. When the ancestors of humans and heptapods first acquired the spark of consciousness, they both perceived the same physical world, but they parsed their perceptions differently; the worldviews that ultimately arose were the end result of that divergence. Humans had developed a sequential mode of awareness, while heptapods had developed a simultaneous mode of awareness. We experienced events in an order, and perceived their relationship as cause and effect. They experienced all events at once, and perceived a purpose underlying them all. A minimizing, maximizing purpose.

Page 168

The heptapods are neither free nor bound as we understand those concepts; they don’t act according to their will, nor are they helpless automatons. What distinguishes the heptapods’ mode of awareness is not just that their actions coincide with history’s events; it is also that their motives coincide with history’s purposes. They act to create the future, to enact chronology. Freedom isn’t an illusion; it’s perfectly real in the context of sequential consciousness. Within the context of simultaneous consciousness, freedom is not meaningful, but neither is coercion; it’s simply a different context, no more or less valid than the other. It’s like that famous optical illusion, the drawing of either an elegant young woman, face turned away from the viewer, or a wart-nosed crone, chin tucked down on her chest. There’s no ‘correct’ interpretation; both are equally valid. But you can’t see both at the same time. Similarly, knowledge of the future was incompatible with free will. What made it possible for me to exercise freedom of choice also made it impossible for me to know the future. Conversely, now that I know the future, I would never act contrary to that future, including telling others what I know: those who know the future don’t talk about it. Those who’ve read the Book of Ages never admit to it.

Note: Their motives coincide with history’s purposes.

“I never act contrary to the future” - unlike Dark’s characters.

Page 180

The negotiator was describing humans’ moral beliefs, trying to lay some groundwork for the concept of altruism. I knew the heptapods were familiar with the conversation’s eventual outcome, but they still participated enthusiastically. If I could have described this to someone who didn’t already know, she might ask, if the heptapods already knew everything that they would ever say or hear, what was the point of their using language at all? A reasonable question. But language wasn’t only for communication: it was also a form of action. According to speech act theory, statements like ‘You’re under arrest,’ ‘I christen this vessel,’ or ‘I promise’ were all performative: a speaker could perform the action only by uttering the words. For such acts, knowing what would be said didn’t change anything. Everyone at a wedding anticipated the words ‘I now pronounce you husband and wife,’ but until the minister actually said them, the ceremony didn’t count. With performative language, saying equaled doing. For the heptapods, all language was performative. Instead of using language to inform, they used language to actualize. Sure, heptapods already knew what would be said in any conversation; but in order for their knowledge to be true, the conversation would have to take place.

Page 347

‘Why do they even bother calling it natural philosophy?’ said Robert. ‘Just admit it’s another theology lesson and be done with it.’ The two of them had recently purchased A Boy’s Guide to Nomenclature, which informed them that nomenclators no longer spoke in terms of God or the divine name. Instead, current thinking held that there was a lexical universe as well as a physical one, and bringing an object together with a compatible name caused the latent potentialities of both to be realized. Nor was there a single ‘true name’ for a given object: depending on its precise shape, a body might be compatible with several names, known as its ‘euonyms,’ and conversely a simple name might tolerate significant variations in body shape, as his childhood marching doll had demonstrated.

Note: What a fascinating idea.

Page 454

Instead Neil became actively resentful of God. Sarah had been the greatest blessing of his life, and God had taken her away. Now he was expected to love Him for it? For Neil, it was like having a kidnapper demand love as ransom for his wife’s return. Obedience he might have managed, but sincere, heartfelt love? That was a ransom he couldn’t pay.

Page 713

Neil still loves Sarah, and misses her as much as he ever did, and the knowledge that he came so close to rejoining her only makes it worse. He knows his being sent to Hell was not a result of anything he did; he knows there was no reason for it, no higher purpose being served. None of this diminishes his love for God. If there were a possibility that he could be admitted to Heaven and his suffering would end, he would not hope for it; such desires no longer occur to him. Neil even knows that by being beyond God’s awareness, he is not loved by God in return. This doesn’t affect his feelings either, because unconditional love asks nothing, not even that it be returned. And though it’s been many years that he has been in Hell, beyond the awareness of God, he loves Him still. That is the nature of true devotion.

Note: Sounds like brainwashing

Page 350

Division by Zero There’s a famous equation that looks like this: eiπ + 1 = 0 When I first saw the derivation of this equation, my jaw dropped in amazement. Let me try to explain why. One of the things we admire most in fiction is an ending that is surprising, yet inevitable. This is also what characterizes elegance in design: the invention that’s clever yet seems totally natural. Of course we know that they aren’t really inevitable; it’s human ingenuity that makes them seem that way, temporarily. Now consider the equation mentioned above. It’s definitely surprising; you could work with the numbers e, π, and i for years, each in a dozen different contexts, without realizing they intersected in this particular way. Yet once you’ve seen the derivation, you feel that this equation really is inevitable, that this is the only way things could be. It’s a feeling of awe, as if you’ve come into contact with absolute truth. A proof that mathematics is inconsistent, and that all its wondrous beauty was just an illusion, would, it seemed to me, be one of the worst things you could ever learn.

Note: This man really loves mathematics. I could tell just by reading that story. The main characters angst felt too genuine to be something second hand.