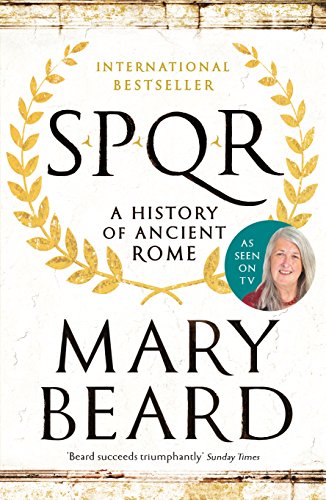

SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome

by Mary Beard

- Author:

- Mary Beard

- Status:

- Done

- Format:

- eBook

- Genres:

- History , Nonfiction , Ancient History , Historical , Italy , Roman History

- Pages:

- 606

- Highlights:

- 147

Highlights

Page 115

Yet the history of ancient Rome has changed dramatically over the past fifty years, and even more so over the almost 250 years since Edward Gibbon wrote The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, his idiosyncratic historical experiment that began the modern study of Roman history in the English-speaking world. That is partly because of the new ways of looking at the old evidence, and the different questions we choose to put to it. It is a dangerous myth that we are better historians than our predecessors. We are not. But we come to Roman history with different priorities – from gender identity to food supply – that make the ancient past speak to us in a new idiom.

Note: Very good point about not being better historians

Page 128

Roman history is always being rewritten, and always has been; in some ways we know more about ancient Rome than the Romans themselves did. Roman history, in other words, is a work in progress. This book is my contribution to that bigger project; it offers my version of why it matters.

Note: Bold claim that we know more than they did

Page 152

Rome was not simply the thuggish younger sibling of classical Greece, committed to engineering, military efficiency and absolutism, whereas the Greeks preferred intellectual inquiry, theatre and democracy. It suited some Romans to pretend that was the case, and it has suited many modern historians to present the classical world in terms of a simple dichotomy between two very different cultures. That is, as we shall see, misleading, on both sides. The Greek city-states were as keen on winning battles as the Romans were, and most had little to do with the brief Athenian democratic experiment. Far from being unthinking advocates of imperial might, several Roman writers were the most powerful critics of imperialism there have ever been. ‘They create desolation and call it peace’ is a slogan that has often summed up the consequences of military conquest. It was written in the second century CE by the Roman historian Tacitus, referring to Roman power in Britain.

Note: Nuance doesn’t fit in 140 characters, but this was a problem long before social media I guess

Page 198

It is only in the first century BCE that we can start to explore Rome, close up and in vivid detail, through contemporary eyes. An extraordinary wealth of words survives from this period: from private letters to public speeches, from philosophy to poetry – epic and erotic, scholarly and straight from the street. Thanks to all this, we can still follow the day-to-day wheeling and dealing of Rome’s political grandees. We can eavesdrop on their bargaining and their trade-offs and glimpse their back-stabbing, metaphorical and literal. We can even get a taste of their private lives: their marital tiffs, their cash-flow problems, their grief at the death of beloved children, or occasionally of their beloved slaves. There is no earlier period in the history of the West that it is possible to get to know quite so well or so intimately (we have nothing like such rich and varied evidence from classical Athens). It is not for more than a millennium, in the world of Renaissance Florence, that we find any other place that we can know in such detail again.

Page 239

Whatever its rights and wrongs, ‘The Conspiracy’ takes us to the centre of Roman political life in the first century BCE, to its conventions, controversies and conflicts. In doing so, it allows us to glimpse in action the ‘Senate’ and the ‘Roman People’ – the two institutions whose names are embedded in my title, SPQR (Senatus PopulusQue Romanus). Individually, and sometimes in bitter opposition, these were the main sources of political authority in first-century BCE Rome. Together they formed a shorthand slogan for the legitimate power of the Roman state, a slogan that lasted throughout Roman history and continues to be used in Italy in the twenty-first century CE. More widely still, the senate (minus the PopulusQue Romanus) has lent its name to modern legislative assemblies the world over, from the USA to Rwanda.

Page 278

Catiline himself had a successful early career and was elected to a series of junior political offices, but in 63 BCE he was close to bankruptcy. A string of crimes was attached to his name, from the murder of his first wife and his own son to sex with a virgin priestess. But whatever his expensive vices, his financial problems came partly from his repeated attempts to secure election as one of the two consuls, the most powerful political posts in the city.

Note: I see the difference between Beard and other historians. This is meant for popular consumption. That’s why she doesn’t say “quaestor” or “vestal virgin”

Page 286

That was Catiline’s position after he had been beaten in the annual elections for the consulship in both 64 and 63 BCE. Although the usual story is that he had been leaning in that direction before, he now had little option but to resort to ‘revolution’ or ‘direct action’ or ‘terrorism’, whichever you choose to call it. Joining forces with other upper-class desperadoes in similar straits, he appealed to the support of the discontented poor within the city while mustering his makeshift army outside it. And there was no end to his rash promises of debt relief (one of the most despicable forms of radicalism in the eyes of the Roman landed classes) or to his bold threats to take out the leading politicians and to put the whole city to flames.

Note: That tool David Graeber probably salivating at this

Page 339

And togas were white, with the addition of a purple border for anyone who held public office. In fact, the modern word ‘candidate’ derives from the Latin candidatus, which means ‘whitened’ and refers to the specially whitened togas that Romans wore during election campaigns, to impress the voters. In a world where status needed to be on show, the niceties of dress went even further: there was also a broad purple stripe on senators’ tunics, worn beneath the toga, and a slightly narrower one if you were the next rank down in Roman society, an ‘equestrian’ or ‘knight’, and special shoes for both ranks.

Note: I enjoy learning tidbits like this. Especially ways in which historical quirks influence modern life

Page 406

So far in this story the Populus(Que) Romanus (the PQR in SPQR) has not played a particularly prominent role. The ‘people’ was a much larger and amorphous body than the senate, made up, in political terms, of all male Roman citizens; the women had no formal political rights. In 63 BCE that was around a million men spread across the capital and throughout Italy, as well as a few beyond. In practice, it usually comprised the few thousand or the few hundred who, on any particular occasion, chose to turn up to elections, votes or meetings in the city of Rome. Exactly how influential the people were has always – even in the ancient world – been one of the big controversies in Roman history; but two things are certain. At this period, they alone could elect the political officials of the Roman state; no matter how blue-blooded you were, you could only hold office as, say, consul if the Roman people elected you. And they alone, unlike the senate, could make law. In 58 BCE Cicero’s enemies argued that, whatever authority he had claimed under the senate’s prevention of terrorism decree, his executions of Catiline’s followers had flouted the fundamental right of any Roman citizen to a proper trial. It was up to the people to exile him.

Note: This distinction between the two is fascinating

Page 426

The single most extraordinary fact about the Roman world is that so much of what the Romans wrote has survived, over two millennia. We have their poetry, letters, essays, speeches and histories, to which I have already referred, but also novels, geographies, satires and reams and reams of technical writing on everything from water engineering to medicine and disease. The survival is largely due to the diligence of medieval monks who transcribed by hand, again and again, what they believed were the most important, or useful, works of classical literature, with a significant but often forgotten contribution from medieval Islamic scholars who translated into Arabic some of the philosophy and scientific material. And thanks to archaeologists who have excavated papyri from the sands and the rubbish dumps of Egypt, wooden writing tablets from Roman military bases in the north of England and eloquent tombstones from all over the empire, we have glimpses of the life and letters of some rather more ordinary inhabitants of the Roman world. We have notes sent home, shopping lists, account books and last messages inscribed on graves. Even if this is a small proportion of what once existed, we have access to more Roman literature – and more Roman writing in general – than any one person could now thoroughly master in the course of a lifetime.

Note: Even more than what’s mentioned. We have graves of pets, graffiti from Pompei. But this sticks to the authors goal of analysing how and why we know what we know, rather than merely what

Page 494

It did not take long for the opening words of Cicero’s speech given on 8 November (the First Catilinarian) to become one of the best known and instantly recognisable quotes of the Roman world: ‘Quo usque tandem abutere, Catilina, patientia nostra?’ (‘How long, Catiline, will you go on abusing our patience?’); and it was closely followed, a few lines later in the written text, by the snappy, and still much repeated, slogan ‘O tempora, o mores’ (‘O what a world we live in!’, or, literally, ‘O the times, O the customs!’). In fact, the phrase ‘Quo usque tandem …’ must already have been firmly embedded in the Roman literary consciousness by the time that Sallust was writing his account of the ‘war’, just twenty years later. So firmly embedded was it that, in pointed or playful irony, Sallust could put it into Catiline’s mouth. ‘Quae quo usque tandem patiemini, o fortissimi viri?’ (‘How long will you go on putting up with this, my braves?’) is how Sallust’s revolutionary stirs up his followers, reminding them of the injustices they were suffering at the hands of the elite. The words are purely imaginary. Ancient writers regularly scripted speeches for their protagonists, much as historians today like to ascribe feelings or motives to their characters. The joke here is that Catiline, Cicero’s greatest enemy, is made to voice his antagonist’s most famous slogan.

Note: Good point about how modern historians act. I hadn’t thought about that, like it was just taken for granted.

Page 522

Might there not be another side to the story? The detailed evidence we have from Cicero’s pen, or point of view, means that his perspective will always be dominant. But it does not necessarily mean that it is true in any simple sense, or that it is the only way of seeing things. People have wondered for centuries quite how loaded an account Cicero offers us, and have detected alternative views and interpretations just beneath the surface of his version of events. Sallust himself hints as much. For, although his account is heavily based on Cicero’s writing, by transferring the famous ‘Quo usque tandem’ from the mouth of Cicero to that of Catiline, he may well have been reminding his readers that the facts and their interpretations were, at the very least, fluid.

Note: History was written by the Victor, or in this case, the survivor and superior orator

Page 548

Cicero casts Catiline as a desperado with terrible gambling debts, thanks entirely to his moral failings. But the situation cannot have been so simple. There was some sort of credit crunch in Rome in 63 BCE, and more economic and social problems than Cicero was prepared to acknowledge. Another achievement of his ‘great consulate’ was to scotch a proposal to distribute land in Italy to some of the poor in the city. To put it another way, if Catiline behaved like a desperado, he might have had a good reason, and the support of many ordinary people driven to desperate measures by similar distress.

Page 565

According to these calculations, the number of coins being minted in the late 60s BCE fell so sharply that there were fewer overall in circulation than there had been a few years before. The reasons for this we cannot reconstruct. Like most states before the eighteenth century or even later, Rome had no monetary policy as such, nor any financial institutions where that kind of policy could be developed. But the likely consequences are obvious. Whether he recklessly gambled away his fortune or not, Catiline – and many others – might have been short of cash; while those already in debt would have been faced with creditors, short of cash themselves, calling in their loans.

Page 578

Cicero, inevitably, had an interest in making the most of the danger that Catiline posed. Whatever his political success, he held a precarious position at the top of Roman society, among aristocratic families who claimed, like Catiline, a direct line back to the founders of the city, or even to the gods. Julius Caesar’s family, for example, was proud to trace its lineage back to the goddess Venus; another, more curiously, claimed descent from the equally mythical Pasiphae, the wife of King Minos, whose extraordinary coupling with a bull produced the monstrous Minotaur. In order to secure his position in these circles, Cicero was no doubt looking to make a splash during his year as consul. An impressive military victory against a barbarian enemy would have been ideal, and what most Romans would have dreamt of. Rome was always a warrior state, and victory in war the surest route to glory. Cicero, however, was no soldier: he had come to prominence in the law courts, not by leading his army in battle against dangerous, or unfortunate, foreigners. He needed to ‘save the state’ in some other way.

Note: Persuasive theory. Feels a bit conspiracy like, but the claim isn’t that Cicero made the whole thing up. Just that he portrayed himself in the best possible light

Page 732

As soon as she gave birth, to twins, Amulius ordered his servants to throw the babies into the nearby river Tiber to drown. But they survived. For, as often happens in stories like this in many cultures, the men who had been given this unpleasant task did not (or could not bring themselves to) follow the instructions to the letter. Instead, they left the twins in a basket not directly in the river but – as it was in flood – next to the water that had burst its banks. Before the babies were washed away to their death, the famous nurturing wolf came to their rescue. Livy was one of those Roman sceptics who tried to rationalise this particularly implausible aspect of the tale. The Latin word for ‘wolf’ (lupa) was also used as a colloquial term for ‘prostitute’ (lupanare was one standard term for ‘brothel’). Could it be that a local whore rather than a local wild beast had found and tended the twins?

Note: Now that the author mentions it, that trope is used a lot across cultures

Page 744

The twins disagreed about where exactly to site their new foundation – in particular, which one of the several hills that later made up the city (there are, in fact, more than the famous seven) should form the centre of the first settlement. Romulus chose the hill known as the Palatine, where the emperors’ grand residence later stood and which has given us our word ‘palace’.

Note: Love the trivia

Page 746

In the quarrel that ensued, Remus, who had opted for the Aventine, insultingly jumped over the defences that Romulus was constructing around his preferred spot. There were various versions of what happened next. But the commonest (according to Livy) was that Romulus responded by killing his brother and so became the sole ruler of the place that took his name. As he struck the terrible, fratricidal blow, he shouted (in Livy’s words): ‘So perish anyone else who shall leap over my walls.’ It was an appropriate slogan for a city which went on to portray itself as a belligerent state, but one whose wars were always responses to the aggression of others, always ‘just’.

Note: That is true! These dudes were obsessed with finding casus belli

Page 779

Livy defends the early Romans. He insists that they seized only unmarried women; this was the origin of marriage, not of adultery. And by stressing the idea that the Romans did not choose the women but took them at random, he argues that they were resorting to a necessary expedient for the future of their community, which was followed by loving talk and promises of affection from the men to their new brides. He also presents the Roman action as a response to the unreasonable behaviour of the city’s neighbours. The Romans, he explains, had first done the correct thing, by asking the surrounding peoples for a treaty which would have given them the right to marry each other’s daughters. Livy explicitly – and wildly anachronistically – refers here to the legal right of conubium, or ‘intermarriage’, which much later was a regular part of Rome’s alliances with other states. The Romans turned to violence only when that request was unreasonably rebuffed. That is to say, this was another case of a ‘just war’.

Note: These dudes were massively delusional. Just indeed.

Page 830

The only thing recorded about this Egnatius is that he overturned the story of the murder entirely and asserted that Remus survived to a ripe old age, actually outliving his twin. It was a desperate, and no doubt unconvincing, attempt to escape the bleak message of the story: that fratricide was hard-wired into Roman politics and that the dreadful bouts of civil conflict that repeatedly blighted Rome’s history from the sixth century BCE on (the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE being only one example) were somehow predestined. For what city, founded on the murder of brother by brother, could ever escape the murder of citizen by citizen? The poet Quintus Horatius Flaccus (‘Horace’) was just one writer of many who answered that question in the obvious way. Writing around 30 BCE, in the aftermath of the decade of fighting that followed Caesar’s death, he lamented: ‘Bitter fate pursues the Romans, and the crime of a brother’s murder, ever since the blood of blameless Remus was spilt onto the ground to be a curse on his descendants.’ Civil war, we might say, was in the Roman genes.

Page 846

Edgy in a different way was the idea of the asylum, and the welcome, that Romulus gave to all comers – foreigners, criminals and runaways – in finding citizens for his new town. There were positive aspects to this. In particular, it reflected Roman political culture’s extraordinary openness and willingness to incorporate outsiders, which set it apart from every other ancient Western society that we know. No ancient Greek city was remotely as incorporating as this; Athens in particular rigidly restricted access to citizenship. This is not a tribute to any ‘liberal’ temperament of the Romans in the modern sense of the word. They conquered vast swathes of territory in Europe and beyond, sometimes with terrible brutality; and they were often xenophobic and dismissive of people they called ‘barbarians’. Yet, in a process unique in any pre-industrial empire, the inhabitants of those conquered territories, ‘provinces’ as Romans called them, were gradually given full Roman citizenship, and the legal rights and protections that went with it. That culminated in 212 CE (where my SPQR ends), when the emperor Caracalla made every free inhabitant of the empire a Roman citizen.

Note: By co-opting local elites, they cemented their power. I guess this was “inclusivity” by ancient standards

Page 860

Even before then, the elite of the provinces had entered the political hierarchy of the capital, in large numbers. The Roman senate gradually became what we might now describe as a decidedly multicultural body, and the full list of Roman emperors contains many whose origins lay outside Italy: Caracalla’s father, Septimius Severus, was the first emperor from Roman territory in Africa; Trajan and Hadrian, who reigned half a century earlier, had come from the Roman province of Spain. When in 48 CE the emperor Claudius – whose avuncular image owes more to Robert Graves’ novel I, Claudius than to real life – was arguing to a slightly reluctant senate that citizens from Gaul should be allowed to become senators, he spent some time reminding the meeting that Rome had been open to foreigners from the beginning. The text of his speech, including some of the heckling that apparently even an emperor had to endure, was inscribed on bronze and put on display in the province, in what is now the city of Lyon, where it still survives. Claudius, it seems, did not get the chance that Cicero had to make adjustments for publication.

Note: These dudes were far thinking

Page 869

There was a similar process with slavery. Roman slavery was in some respects as brutal as Roman methods of military conquest. But for many Roman slaves, particularly those working in urban domestic contexts rather than toiling in the fields or mines, it was not necessarily a life sentence. They were regularly given their freedom, or they bought it with cash they had managed to save up; and if their owner was a Roman citizen, then they also gained full Roman citizenship, with almost no disadvantages as against those who were freeborn. The contrast with classical Athens is again striking: there, very few slaves were freed, and those who were certainly did not gain Athenian citizenship in the process, but went into a form of stateless limbo. This practice of emancipation – or manumission, to follow the Latin term – was such a distinctive feature of Roman culture that outsiders at the time remarked upon it and saw it as a powerful factor in Rome’s success. As one king of Macedon observed in the third century BCE, it was in this way that ‘the Romans have enlarged their country’. The scale was so great that some historians reckon that, by the second century CE, the majority of the free citizen population of the city of Rome had slaves somewhere in their ancestry.

Note: Slavers, but with policies that made the state stronger in the long run

Page 882

In the late first or early second century CE, the satiric poet ‘Juvenal’ – Decimus Junius Juvenalis – who loved to pour scorn on Roman pretensions, lambasted the snobbery that was another side of life at Rome, and he ridiculed those aristocrats who boasted of a family tree going back centuries. He ends one of his poems with a sideswipe at Rome’s origins. What are all these pretensions based on, anyway? Rome was from its very beginning a city made up of slaves and runaways (‘Whoever your earliest ancestor was, he was either a shepherd or something I’d rather not mention’). Cicero may have been making a similar point when he joked in a letter to his friend Atticus about the ‘the crap’ or ‘the dregs’ of Romulus. He was poking fun at one of his contemporaries, who, he said, addressed the senate as if he were living ‘in the Republic of Plato’, referring to the philosopher’s ideal state – ‘when in fact he is in the faex (crap) of Romulus.’

Note: Fascinating

Page 918

But gradually the different views coalesced around the middle of what we call the eighth century BCE, as scholarly opinion reached the conclusion that Greek and Roman history ‘began’ at roughly the same time. What became the canonical date, and one still quoted in many modern textbooks, partly goes back to a scholarly treatise, the Book of Chronology, by none other than Cicero’s friend and correspondent Atticus. It does not survive, but it is supposed to have pinpointed Romulus’ foundation of the city to the third year of the sixth cycle of Olympic Games; that is to say, 753 BCE. Other calculations narrowed this down further, to 21 April, the date on which modern Romans still, to this day, celebrate the birthday of their city, with some rather tacky parades and mock gladiatorial spectacles.

Note: Alright, completely made up then

Page 924

There is often a fuzzy boundary between myth and history (think of King Arthur or Pocahontas), and, as we shall see, Rome is one of those cultures where that boundary is particularly blurred. But despite all the historical acumen that Romans brought to bear on this story, there is every reason for us to see it, in our terms, as more or less pure myth. For a start, there was almost certainly no such thing as a founding moment of the city of Rome. Very few towns or cities are founded at a stroke, by a single individual. They are usually the product of gradual changes in population, in patterns of settlement, social organisation and sense of identity. Most ‘foundations’ are retrospective constructions, projecting back into the distant past a microcosm, or imagined primitive version, of the later city. The name ‘Romulus’ is itself a give-away. Although Romans usually assumed that he had lent his name to his newly established city, we are now fairly confident that the opposite was the case: ‘Romulus’ was an imaginative construction out of ‘Roma’. ‘Romulus’ was merely the archetypal ‘Mr Rome’.

Page 948

Of course, to put it another way, it is precisely because the story of Romulus is mythic rather than historical, in the narrow sense, that it encapsulates so sharply some of the central cultural questions of ancient Rome and is so important for understanding Roman history, in its wider definition. The Romans had not, as they assumed, simply inherited the priorities and concerns of their founder. Quite the reverse: over centuries of retelling and then rewriting the story, they themselves had constructed and reconstructed the founding figure of Romulus as a powerful symbol of their preferences, debates, ideologies and anxieties. It was not, in other words, to go back to Horace, that civil war was the curse and destiny of Rome from its birth; Rome had projected its obsessions with the apparently unending cycle of civil conflict back onto its founder.

Page 018

The message is clear: however far back you go, the inhabitants of Rome were always already from somewhere else.

Page 292

Livy, for example, quotes the very first Roman historian, Quintus Fabius Pictor, who wrote around 200 BCE and claimed that towards the end of the regal period the number of adult male citizens was 80,000, making a total population of well over 200,000. This is a ludicrous figure for a new community in archaic Italy (it is not far short of the total population of the territories of Athens or Sparta at their height, in the mid fifth century BCE), and there is no archaeological evidence for a city of any such size at this time, although the number does at least have the virtue of matching the aggrandising views of early Rome found in all ancient writers.

Note: At least they were consistent

Page 301

Military activity is another good case in point. Here geography alone should give us pause. We need simply look at the location of these heroic battles: they were all fought within a radius of about 12 miles of the city of Rome. Despite the style in which they are recounted, as if they were mini-versions of Rome against Hannibal, they were probably something closer, in our terms, to cattle raids. They may not even have been ‘Roman’ engagements in the strict sense of the word at all. In most early communities, it took a long time before the various forms of private violence, from rough justice and vendetta to guerrilla warfare, came fully under public control. Conflict of all sorts was regularly in the hands of individuals with their own following, the ancient equivalents of what we might call private warlords; and there was a blurry distinction between what was conducted on behalf of the ‘state’ and what on behalf of some powerful leader. Almost certainly that was the case in early Rome.

Page 364

This did not make Numa a holy figure along the lines of Moses, the Buddha, Jesus or Muhammad. The traditional religion of Rome was significantly different from religion as we usually understand it now. So much modern religious vocabulary – including the word ‘religion’, as well as ‘pontiff’ – is borrowed from Latin that it tends to obscure some of the major differences between ancient Roman religion and our own. In Rome there was no doctrine as such, no holy book and hardly even what we would call a belief system. Romans knew the gods existed; they did not believe in them in the internalised sense familiar from most modern world religions. Nor was ancient Roman religion particularly concerned with personal salvation or morality. Instead it mainly focused on the performance of rituals that were intended to keep the relationship between Rome and the gods in good order, and so ensure Roman success and prosperity. The sacrifice of animals was a central element in most of these rituals, which otherwise were extraordinarily varied. Some were so outlandish that they undermine better than anything else the modern stereotype of the Romans as stuffy and sedate: at the festival of Lupercalia in February, for example, naked young men ran round the city whipping any women they met (this is the festival that the opening scene of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar re-creates). In general, it was a religion of doing, not believing.

Page 381

Among all the things we fancy we have inherited from ancient Rome, from drains to place names, or the offices of the Catholic Church, the calendar is probably the most important and the most often overlooked. It is a surprising link between that early regal period and our world.

Page 393

In fact, the earliest written version of a Roman calendar that we have – although itself from no earlier than the first century BCE – points strongly in that direction. It is an extraordinary survival, found painted on a wall in the town of Antium (modern Anzio), some 35 miles south of Rome, and offers a vivid, if slightly perplexing, glimpse of how Romans of Cicero’s time pictured their year. Nothing in early Rome would have been as complex as this. There are signs of all kinds of developments over the centuries, including some radical changes in the ordering of months and in the starting point of the year – for how else could November and December, meaning literally ‘ninth month’ and ‘tenth month’, respectively, have ended up in this calendar, and our own, as the eleventh and twelfth months in the sequence? But there are also hints of an ancient pedigree in this first-century BCE version.

Note: I wonder if any Roman author opined on this

Page 401

Its system is basically one of twelve lunar months, with an extra month (the distant precursor of our extra day in a leap year) inserted from time to time to keep this calendar in proper alignment with the solar year. The biggest challenge facing primitive calendars everywhere is the fact that the two most obvious, natural systems of timekeeping are incompatible: that is to say, twelve lunar months, from new moon to new moon, add up to just over 354 days; and this cannot be made to match in any convenient way the 365¼ days of the solar year, which is the time it takes for the earth to make one complete circuit of the sun, from spring equinox to spring equinox, for instance. The wholesale insertion of an extra month every few years is just the kind of rough-and-ready method typical of early attempts to solve the problem.

Note: Honestly, it’s a reasonable solution

Page 458

Cicero reflects exactly that when he sums up Servius Tullius’ political objectives in approving tones: ‘He divided the people in this way to ensure that voting power was under the control not of the rabble but of the wealthy, and he saw to it that the greatest number did not have the greatest power – a principle that we should always stand by in politics.’ In fact, this principle came to be vigorously contested in the politics of Rome.

Page 685

The end of the monarchy was also the birth of liberty and of the free Roman Republic. For the rest of Roman history, ‘king’, or rex, was a term of loathing in Roman politics, despite the fact that so many of Rome’s defining institutions were supposed to have their origins in the regal period. There were any number of cases in the centuries that followed when the accusation that he was aiming at kingship brought a swift end to a man’s political career. His royal name even proved disastrous for Lucretia’s unfortunate widower, who, because he was a relation of the Tarquins, was shortly sent into exile. In foreign conflicts too, kings were the most desirable of enemies. Over the next few hundred years, there was always a particular frisson when a triumphal procession through the streets of the city paraded some enemy king in all his regal finery for the Roman populace to jeer and pelt.

Page 729

The Republic, in other words, was not just a political system. It was a complex set of interrelationships between politics, time, geography and the Roman cityscape. Dates were directly correlated with the elected consuls; years were marked by the nails hammered into the temple whose dedication was traced back to the first year of the new regime; even the island in the Tiber was a product, quite literally, of the expulsion of the kings. Underpinning the whole thing was one single, overriding principle: namely, freedom, or libertas.

Page 792

The epitaph was composed soon after his death. It is four lines long and must count as the earliest historical and biographical narrative to survive from ancient Rome. Short as it is, it is one of the major turning points in our understanding of Roman history. For it provides hard, more or less contemporary information on Barbatus’ career – quite different from the imaginative reconstructions, faint hints buried in the soil or modern deductions about ‘what must have been’ that surround the fall of the monarchy. It is eloquent on the ideology and world view of the Roman elite at this period: ‘Cornelius Lucius Scipio Barbatus, offspring of his father Gnaeus, a brave man and wise, whose appearance was a match for his virtus. He was consul and censor and aedile among you. He took Taurasia and Cisauna from Samnium. He subdued the whole of Lucania and took hostages.’

Page 862

Not that this was a story of unchallenged expansion. Soon after the defeat of Veii, in 390 BCE a posse of marauding ‘Gauls’ sacked Rome. Exactly who these people were is now impossible to know; Roman writers were not good at distinguishing between those whom it was convenient to lump together as ‘barbarian tribes’ from the north, nor much interested in analysing their motives. But according to Livy, the effects were so devastating that the city had to be refounded (yet again), under the leadership of Marcus Furius Camillus – war leader, dictator, ‘colonel’, sometime exile and another ‘second Romulus’.

Page 938

It is a much simpler society, and its horizons much more restricted, than Livy’s account ever implies. That is clear from the language and forms of expression as much as from the content. Although modern translations do their best to make it all sound fairly lucid, the original Latin wording is often far from that. In particular, the absence of nouns and differentiated pronouns can make it almost impossible to know who is doing what to whom. ‘If he summons to law, he is to go. If he does not go, he is to call to witness, then is to seize him’ presumably means, as it is usually translated, ‘If a plaintiff summons a defendant to law, the defendant is to go. If he does not go, the plaintiff is to call someone else to witness, then is to seize the defendant.’ But it does not exactly say that. All the signs are that whoever drafted this and many other clauses was still struggling to use written language to frame precise regulations, and that the conventions of logical argument and rational expression were very much in their infancy.

Page 978

To judge from the Twelve Tables, Rome in the mid fifth century BCE was an agricultural town, complex enough to recognise basic divisions between slave and free and between different ranks of citizen and sophisticated enough to have devised some formal civic procedures to deal consistently with disputes, to regulate social and family relations and to impose some basic rules on such human activities as the disposal of the dead. But there is no evidence that it was more than that. The strikingly tentative formulation of the regulations, in places awkward or even confusing, should call into question some of the references in Livy and other ancient writers to complicated laws and treaties at this period. And the absence, at least from the selection of clauses preserved, of any reference to a specific public official, apart from a Vestal Virgin (who as a priestess was to be free of her father’s control), certainly does not suggest a dominant state apparatus. What is more, there is hardly any mention of the world outside Rome – beyond a couple of references to how particular rules applied to a hostis (a ‘foreigner’ or an ‘enemy’; the same Latin word, significantly, can mean both) and one possible reference to sale into slavery ‘in foreign country across the Tiber’, as a punishment of last resort for debt. Maybe this collection had an intentionally internal rather than external focus. All the same, there is no hint in the Twelve Tables that this was a community putting a high priority on relations, whether of dominance, exploitation or friendship, beyond its locality.

Page 997

In Rome it was seen ever after as a heroic vindication of the political liberty of the ordinary citizen, and it has left its mark on the politics, and political vocabulary, of the modern world too. The word ‘plebeian’ remains an especially loaded term in our class conflicts; even in 2012, the allegation that a British Conservative politician had insulted a policeman by calling him a ‘pleb’ – short for ‘plebeian’ – led to his resignation from the government.

Page 000

As the story of this conflict unfolds, it was only a few years after the Republic had been established, at the beginning of the fifth century BCE, that the plebeians began objecting to their exclusion from power and their exploitation by the patricians. Why fight in Rome’s wars, they repeatedly asked, when all the profits of their service lined patrician pockets? How could they count themselves full citizens when they were subject to random and arbitrary punishment, even enslavement if they fell into debt? What right had the patricians to keep the plebeians as an underclass? Or, as Livy scripted the ironic words of one plebeian reformer, in terms uncannily reminiscent of twentieth-century opposition to apartheid, ‘Why don’t you pass a law to stop a plebeian from living next door to a patrician, or walking down the same street, or going to the same party, or standing side by side in the same Forum?’

Note: It’s true. It’s the same struggle.

Page 007

In 494 BCE, plagued by problems of debt, the plebeians staged the first of several mass walkouts from the city, a combination of a mutiny and a strike, to try to force reform on the patricians. It worked. For it launched a long series of concessions which gradually eroded all the significant differences between patricians and plebeians and effectively rewrote the political power structure of the city. Two hundred years later there was little to patrician privilege beyond the right to hold a few ancient priesthoods and to wear a particular form of fancy footwear.

Note: Good for them

Page 016

Finally, after one last walkout, in a reform that Scipio Barbatus would have witnessed in 287 BCE, the decisions of this assembly were given the automatic binding force of law over all Roman citizens. A plebeian institution, in other words, was given the right to legislate over, and on behalf of, the state as a whole.

Page 019

Between 494 and 287 BCE, amid yet more stirring rhetoric, strikes and threats of violence, all major offices and priesthoods were step by step opened up to plebeians and their second-class status was dismantled. One of the most famed plebeian victories came in 326 BCE, when the system of enslavement for debt was abolished, establishing the principle that the liberty of a Roman citizen was an inalienable right. An equally significant but more narrowly political milestone had been passed forty years earlier, in 367 BCE. After decades of dogged refusal and claims by hard-line patricians that ‘it would be a crime against the gods to let a plebeian be consul,’ it was decided to open one of the consulships to plebeians. From 342 BCE it was agreed that both consuls could be plebeian, if so elected.

Note: Crime against the gods wow. Fighting words.

Page 053

This story of the Conflict of the Orders adds up to one of the most radical and coherent manifestos of popular power and liberty to survive from the ancient world – far more radical than anything to survive from classical democratic Athens, most of whose writers, when they had anything explicitly to say on the subject, were opposed to democracy and popular power. Taken together, the demands put into the mouths of the plebeians offered a systematic programme of political reform, based on different aspects of the freedom of the citizen, from freedom to participate in the government of the state and freedom to share in its rewards to freedom from exploitation and freedom of information. It is hardly surprising that working class movements in many countries in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries found a memorable precedent, and some winning rhetoric, in the ancient story of how the concerted action of the Roman people wrung concessions from the hereditary patrician aristocracy and secured full political rights for the plebeians. Nor is it surprising that early trades unions could look to the plebeian walkouts as a model for a successful strike.

Page 226

Alexander, he concedes, was a great general, though not without his faults, drunkenness among others. But the Romans had the advantage of not depending on a single charismatic leader. They had depth in their command, supported by extraordinary military discipline. They also, he insisted, could call on far greater numbers of well-trained troops and – thanks to Roman alliances throughout Italy – summon reinforcements more or less at will. His answer, in short, was that, if given the chance, the Romans would have beaten Alexander.

Note: The most delusional homer take. There’s just no way any ancient army would have stood a chance against Alexanders veterans. Maybe Caesar fresh after Gaul, but it’s a stretch. His troops had the experience but not the diversity. The Macedonian cavalry would have given Alexander the edge.

Either way, this ancient discourse is at the level of LeBron vs Jordan. The very premise is kinda dumb 😅

Page 236

Two things are clear and undermine a couple of misleading modern myths about Roman power and ‘character’. First, the Romans were not by nature more belligerent than their neighbours and contemporaries, any more than they were naturally better at building roads and bridges. It is true that Roman culture placed an extraordinarily – for us, uncomfortably – high value on success in fighting. Prowess, bravery and deadly violence in battle were repeatedly celebrated, from the successful general parading through the streets and the cheering crowds in his triumphal procession to the rank-and-file soldiers showing off their battle scars in the middle of political debates in the hope of adding weight to their arguments. In the middle of the fourth century BCE the base of the main platform for speakers in the Forum was decorated with the bronze rams of enemy warships captured from the city of Antium during the Latin War, as if to symbolise the military foundation of Roman political power. The Latin word for ‘rams’, rostra, became the name of the platform and gave modern English its word ‘rostrum’.

Note: Love a good etymology. Agree with what she’s saying about how military prowess and achievements were celebrated

Page 252

Second, the Romans did not plan to conquer and control Italy. No Roman cabal in the fourth century BCE sat down with a map, plotting a land grab in the territorial way that we associate with imperialist nation-states in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. For a start, simple as it sounds, they had no maps. What this implies for how they, or any other ‘precartographic’ people, conceived the world around them, or just over their horizons, is one of history’s great mysteries. I have tended to write of the spread of Roman power through the peninsula of Italy, but no one knows how many – or, realistically, how few – Romans at this date thought of their homeland as part of a peninsula in the way we picture it. A rudimentary version of the idea is perhaps implied by references in literature of the second century BCE to the Adriatic as the Upper Sea and the Tyrrhenian as the Lower Sea, but notably this is on a different orientation from ours, east–west rather than north–south.

Note: Maps. Rarely do we think of those.

Page 260

These Romans saw their expansion more in terms of changing relationships with other peoples than in terms of control of territory. Of course, Rome’s growing power did dramatically transform the landscape of Italy. There was little that was more obviously transformative than a brand-new Roman road striking out across empty fields, or land being annexed and divided up among new settlers. It continues to be convenient to measure Roman power in Italy in terms of geographical area. Yet Roman dominion was primarily over people, not places. As Livy saw, the relations that the Romans formed with those people were the key to the dynamics of early Roman expansion.

Page 264

There was one obligation that the Romans imposed on all those who came under their control: namely, to provide troops for the Roman armies. In fact, for most of those who were defeated by Rome and forced, or welcomed, into some form of ‘alliance’, the only long-term obligation seems to have been the provision and upkeep of soldiers. These peoples were not taken over by Rome in any other way; they had no Roman occupying forces or Roman-imposed government. Why this form of control was chosen is impossible to know. But it is unlikely that any particularly sophisticated, strategic calculation was involved. It was an imposition that conveniently demonstrated Roman dominance while requiring few Roman administrative structures or spare manpower to manage. The troops that the allies contributed were raised, equipped and in part commanded by the locals. Taxation in any other form would have been much more labour-intensive for the Romans; direct control of those they had defeated would have been even more so. The results may well have been unintended, but they were ground-breaking. For this system of alliances became an effective mechanism for converting Rome’s defeated enemies into part of its growing military machine; and at the same time it gave those allies a stake in the Roman enterprise, thanks to the booty and glory that were shared in the event of victory. Once the Romans’ military success started, they managed to make it self-sustaining, in a way that no other ancient city had ever systematically done. For the single most significant factor behind victory at this period was not tactics, equipment, skill or motivation. It was how many men you could deploy. By the end of the fourth century BCE, the Romans had probably not far short of…

Note: But this is somewhat similar to Persian kings right? Every time they conquered a new place, they levied troops from there. But I guess that had more direct control, with a Governor. And there was less of a carrot off shared spoils motivating the allies?

Page 297

The implications, however, were again revolutionary. In extending citizenship to people who had no direct territorial connections with the city of Rome, they broke the link, which most people in the classical world took for granted, between citizenship and a single city. In a systematic way that was then unparalleled, they made it possible not just to become Roman but also to be a citizen of two places at once: one’s home town and Rome. And in creating new Latin colonies all over Italy, they redefined the word ‘Latin’ so that it was no longer an ethnic identity but a political status unrelated to race or geography. This set the stage for a model of citizenship and ‘belonging’ that had enormous significance for Roman ideas of government, political rights, ethnicity and ‘nationhood’. This model was shortly extended overseas and eventually underpinned the Roman Empire.

Note: Remarkable. Why would local elites rebel when they had it pretty good in terms of representation, the cost of compliance was low (in the early years) and the cost of rebellion so high?

Page 317

So far in exploring this period, I have largely kept the internal history of Rome separate from the story of its expansion. It makes for a clearer story, but it tends to obscure the impact of politics at home on relations further afield, and vice versa. By 367 BCE, the Conflict of the Orders had done something far more significant and wide-ranging than simply end political discrimination against the plebeians. It had effectively replaced a governing class defined by birth with one defined by wealth and achievement. That is partly the point of Barbatus’ epitaph: patrician though the Scipio family was, what counts here are the offices he held, the personal qualities he displayed and the battles he won. No achievement was more demonstrable or more celebrated than victory in battle, and the desire for victory among the new elite was almost certainly an important factor in intensifying military activity and encouraging warfare.

Note: I’ve always felt this too. The success of the romans can be attributed to a combination of many things, but IMO the chief factor was that they always had capable leaders in times of need rather than nepo babies. Even people who should have been Nepo babies like Scipio Africanus turned out to be geniuses at war

Page 403

as Polybius sternly put it: ‘Who could be so indifferent or so idle that they did not want to find out how, and under what kind of political organisation, almost the whole of the inhabited world was conquered and fell under the sole power of the Romans in less than fifty-three years, something previously unparalleled?’ Who indeed?

Note: 53? Cmon, it’s more like 100 just considering Carthage. Completely agree that no one can be indifferent though.

Page 602

Predictably, modern historians have found it hard to know quite where to fix the boundary between Polybius the Roman hostage and critic of Roman rule and Polybius the Roman collaborator. He certainly sometimes performed a deft balancing act between his different loyalties, giving behind-the-scenes advice at one point to a distinguished Syrian hostage on how to slip away from his detention, while carefully insisting in his Histories that on the day of the great escape he himself was at home, ‘ill in bed’. But whatever Polybius’ political stance, he had the advantage of knowing both sides of the Roman story, and he had the opportunity to quiz some of the leading Roman players. He dissected Rome’s internal organisation – which he insisted underpinned its success abroad – from a vantage point that combined a couple of decades of first-hand experience with all the sophistication of the Greek political theory in which he had been trained back home. His work is, in effect, one of the earliest surviving attempts at comparative political anthropology.

Page 642

The secret, Polybius suggested, lay in a delicate relationship of checks and balances between consuls, the senate and the people, so that neither monarchy nor aristocracy nor democracy ever entirely prevailed. The consuls, for example, might have had full, monarchical command on campaign, but they had to be elected by the people in the first place, and they depended on the senate for funding – and it was the senate which decided whether the successful general should be awarded a triumph at the end of his campaign, and a vote of the people was required to ratify any treaty that might be made. And so on. It was, Polybius argued, such balances across the political system that produced the internal stability on which Roman external success was built. This is a clever piece of analysis, sensitive to the tiny differences and subtle nuances which distinguish one political system from another. To be sure, in some respects Polybius tries to shoehorn the political life that he witnessed at Rome into a Greek analytical model that does not entirely fit. Saddling his discussion with terms like ‘democracy’ is, for example, deeply misleading. ‘Democracy’ (demokratia) was rooted politically and linguistically in the Greek world. It was never a rallying cry at Rome, even in its limited ancient sense or even for the most radical of Roman popular politicians. In most of the conservative writing that survives, the word means something close to ‘mob rule’. There is little point in asking how ‘democratic’ the politics of Republican Rome were: Romans fought for, and about, liberty, not democracy. Yet, in another way, by nudging his readers to keep sight of the people in their picture of Roman politics and to look beyond the power of the elected officials and the aristocratic senate, Polybius sparked an important debate that is still alive today. How influential was the popular voice in Roman Republican politics? Who controlled Rome? How should we characterise this Roman political system?

Page 682

There are also all kinds of anecdotes about the importance and intensity of canvassing, and how the vote of the people could be won or lost. Polybius tells a curious story about the Syrian king Antiochus IV (Epiphanes, ‘famous’ or even ‘manifest god’), the son of Antiochus the Great, who had been ‘crushed’ by Scipio Asiaticus. As a young man he had lived more than a decade as a hostage in Rome before being swapped for a younger relative, the one whom Polybius later advised on his escape plans. On his return to the East, he took with him a variety of Roman habits that he had picked up during his stay. These mostly came down to displaying a popular touch: talking with anyone he met, giving presents to ordinary people and making the rounds of craftsmen’s shops. But most striking of all, he would dress up in a toga and go around the marketplace as if he were a candidate for election, shaking people by the hand and asking for their vote. This baffled the people in his showy capital city of Antioch, who were not used to this kind of thing from a monarch and nicknamed him Epimanes (‘bonkers’ or, to preserve the pun, ‘fatuous’). But it is clear that one lesson that Antiochus had drawn from Rome was that the common people and their votes were important.

Note: Fascinating anecdote

Page 716

Much like the extension of Roman control within Italy, this expansion overseas in the third and second centuries BCE was more complicated than the familiar myth of the Roman legions marching in, conquering and taking over foreign territory. First, the Romans were not the only agents in the process. They did not invade a world of peace-loving peoples, who were just minding their own business until these voracious thugs came along. However cynical we might rightly be about Roman claims that they went to war only in response to requests for assistance from friends and allies (that has been the excuse for some of the most aggressive wars in history), part of the pressure for Rome to intervene did come from outside.

Note: We always underestimate how much war was going on

Page 742

The silence of our text on the outcome of these approaches hints that things did not go the Abderans’ way. But the snapshot here of rival representatives not merely beating a path to the senate but pressing their case daily on individual senators gives an idea of just how actively and persistently Roman assistance could be sought. And the literally hundreds of statues of individual Romans – as ‘saviours and benefactors’ – put up in the cities of the Greek world show how that intervention, if successful, could be celebrated. We cannot now identify every piece of doublethink behind such words: there was no doubt as much fear and flattery involved as sincere gratitude. But they are a useful reminder that the simple shorthand ‘Roman conquest’ can obscure a wide range of perspectives, motivations and aspirations on every side of the encounter.

Page 755

And Polybius, who visited Spain in the mid second century BCE, wrote of 40,000 miners, mostly slaves no doubt, working just one region of mining territory alone (not literally, perhaps: ‘40,000’ was a common ancient shorthand for ‘a very large number’, like our ‘millions’).

Page 762

Romans took the profits and tried to ensure that they got their own way when they wanted, with the threat of force always in the background. It was not an empire of annexation in the sense that later Romans would understand it. There was no detailed legal framework of control, rules or regulations – or, for that matter, visionary aspirations. At this period, even the Latin word imperium, which by the end of the first century BCE could mean ‘empire’, in the sense of the whole area under direct Roman government, meant something much closer to ‘the power to issue orders that are obeyed’. And provincia (or ‘province’), which became the standard term for a carefully defined subdivision of empire under the control of a governor, was not a geographical term but meant a responsibility assigned to Roman officials. That could be, and often was, an assignment of military activity or administration in a particular place.

Note: Love how words change meaning, especially a word as important as imperium.

Page 774

What was at stake for the Romans was whether they could win in battle and then whether – by persuasion, bullying or force – they could impose their will where, when and if they chose. The style of this imperium is vividly summed up in the story of the last encounter between Antiochus Epiphanes and the Romans. The king was invading Egypt for the second time, and the Egyptians had asked the Romans for help. A Roman envoy, Gaius Popilius Laenas, was dispatched and met Antiochus outside Alexandria. After his long familiarity with the Romans, the king no doubt expected a rather civil meeting. Instead, Laenas handed him a decree of the senate instructing him to withdraw from Egypt immediately. When Antiochus asked for time to consult his advisors, Laenas picked up a stick and drew a circle in the dust around him. There was to be no stepping out of that circle before he had given his answer. Stunned, Antiochus meekly agreed to the senate’s demands. This was an empire of obedience.

Page 832

By the mid second century BCE, well over half the adult male citizens of Rome would have seen something of the world abroad, leaving an unknown number of children where they went. To put it another way, the Roman population had suddenly become by far the most travelled of any state ever in the ancient Mediterranean, with only Alexander the Great’s Macedonians or the traders of Carthage as possible rivals. Even for those who never stepped abroad, there were new imaginative horizons, new glimpses of places overseas and new ways of understanding their place in the world.

Page 894

Was this a simple conservative backlash against newfangled ideas being brought into Rome from outside, a bout of ‘culture wars’ between traditionalists and modernisers? In part, perhaps, it was. But it was also more complicated, and interesting, than that. For all his huffing and puffing, Cato had taught his son Greek, and his surviving writing – notably, a technical essay on farming and agricultural management, and substantial quotations from his speeches and from his history of Italy – shows that he was well practised in the Greek rhetorical tricks that he claimed to deplore. And some of the claims being made about ‘Roman tradition’ were little short of imaginative fantasy. There is no reason whatsoever to suppose that venerable old Romans had watched theatrical performances standing up. The evidence we have suggests quite the reverse. The truth is that Cato’s version of old-fashioned, no-nonsense Roman values was as much an invention of his own day as a defence of long-standing Roman traditions. Cultural identity is always a slippery notion, and we have no idea how early Romans thought about their particular character and what distinguished them from their neighbours. But the distinctive, hard-edged sense of tough Roman austerity – which later Romans eagerly projected back on to their founding fathers and which has remained a powerful vision of Romanness into the modern world – was the product of a powerful cultural clash, in this period of expansion abroad, over what it was to be Roman in this new, wider imperial world, and in the context of such an array of alternatives. To put it another way, ‘Greeknesss’ and ‘Romanness’ were as inseparably bound up as they were polar opposites.

Page 992

Whatever motivations lay behind the violence of 146 BCE, the events of that year were soon seen as a turning point. In one way, they marked the acme of Roman military success. Rome had now annihilated its richest, oldest and most powerful rivals in the Mediterranean world. As Virgil presented it more than a hundred years later in the Aeneid, Mummius, by conquering Corinth, had at last avenged the defeat of Aeneas’ Trojans by the Greeks in the Trojan War. But in another way, the events of 146 BCE were seen as the beginning of the collapse of the Republic and as the herald of a century of civil wars, mass murder and assassinations that led to the return of autocratic rule. Fear of the enemy, so this argument went, had been good for Rome; without any significant external threat, ‘the path of virtue was abandoned for that of corruption’. Sallust was particularly eloquent on the theme.

Note: Agree that an external enemy is needed. America lost its way for the same reason.

Page 037

The first was in 133 BCE, when Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus, a tribune of the people with radical plans to distribute land to the Roman poor, decided to seek a second year in office. To put a stop to this, an unofficial posse of senators and their hangers-on interrupted the elections, bludgeoned Gracchus and hundreds of his supporters to death and threw their bodies into the Tiber. Conveniently forgetting the violence that had accompanied the Conflict of the Orders, many Romans held this to be ‘the first political dispute since the fall of the monarchy to be settled by bloodshed and the death of citizens’. There was soon another. Just over a decade later, Tiberius Gracchus’ brother Gaius met the same fate. He had introduced an even more radical programme of reform, including a subsidised grain allowance for Roman citizens, and was successfully elected tribune for a second time. But in 121 BCE, when he was trying to prevent his legislation from being dismantled, he became the victim of another, more official, posse of senators. On this occasion the bodies of thousands of his supporters clogged the river. And it happened again in 100 BCE, when other reformers were battered to death in the senate house itself, the assailants using tiles from the building’s roof as their weapons.

Note: I was hoping for a lot more analysis of the Gracchi

Page 053

Before the Social War was over, one of its commanders, Lucius Cornelius Sulla, a consul in 88 BCE, became the first Roman since the mythical Coriolanus to lead his army against the city of Rome. Sulla was forcing the hand of the senate to give him command in a war in the East, and when he returned from that victorious four years later, he marched on his home town once again and had himself appointed dictator. Before resigning in 79 BCE, he introduced a wholesale conservative reform programme and presided over a reign of terror and the first organised purge of political enemies in Roman history. In these ‘proscriptions’ (that is, ‘notices’, as they were known, in a chilling euphemism), the names of thousands of men, including about a third of all senators, were posted throughout Italy, a generous price on their heads for anyone cruel, greedy or desperate enough to kill them.

Note: I did not know the extent of Sulla’s proscriptions

Page 078

The essentials of what happened next are clear, even if the details are almost impenetrably complicated. Leaving Gaul in early 49 BCE, Caesar famously crossed the river Rubicon, which formed the boundary of Italy, and marched towards Rome. Forty years had made a big difference. When Sulla turned his army on the city, all but one of his senior officers had refused to follow him. When Caesar did the same, all but one stayed with him. It was an apt symbol of how far scruples had eroded in such a short time.

Note: The next few Jan 6th uprisings won’t see universal unity. More and more, violence will become normalised.

Page 092

It is also a story that historians, both ancient and modern, tell with all the advantages and disadvantages of hindsight. Once the outcome is known, it is easy to present the period as a series of irrevocable and brutal steps in the direction of crisis or as a slow countdown to both the end of the free state and the return of one-man rule. But the last century of the Republic was more than a mere bloodbath. As the flowering of poetry, theory and art suggests, it was also a period when Romans grappled with the issues that were undermining their political process and came up with some of their greatest inventions, including the radical principle that the state had some responsibility for ensuring that its citizens had enough to eat. For the first time, they confronted the question of how an empire should be administered and governed, rather than simply acquired, and devised elaborate codes of practice for Roman rule. In other words, this was also an extraordinary period of political analysis and innovation. Roman senators did not sit idly by as their political institutions lapsed into chaos, nor did they simply fan the flames of the crisis to their own short-term advantage (though there was certainly a bit of that). Many of them, from different ends of the political spectrum, tried to find some effective remedies. We should not allow our hindsight, their ultimate failure or the succession of civil wars and assassinations to blind us to their efforts, which are the main theme of this and the next chapter.

Note: Meta history

Page 120

How far the smallholders really had disappeared from the land has puzzled modern historians much more than it did their ancient counterparts. It is not difficult to see how an agricultural revolution of that kind might have been a logical consequence of Roman warfare and expansion. During the war against Hannibal, at the end of the third century BCE, rival armies had tramped up and down the Italian peninsula for a couple of decades, with devastating effects on the farmland. The demands of service with the army overseas removed manpower from the agricultural workforce for years on end, leaving family farms without essential labour. Both of these factors could have made small-holders particularly vulnerable to failure, bankruptcy or buy-outs by the rich, who used the wealth they acquired from overseas conquest to build up vast land holdings, worked as agricultural ranches by the glut of slave labour. One modern historian echoed the sentiments of Tiberius when he grimly summed this up: whatever booty they came home with, many ordinary soldiers had been in effect ‘fighting for their own displacement’. A good proportion of them would have drifted to Rome or other towns in search of a living, so swelling the urban underclass. It is a plausible scenario. But there is not much hard evidence to back it up. Leaving aside the propagandist tone of Tiberius’ eye-opening journey through Etruria (had he not travelled 40 miles north before?), there are few archaeological traces of the new-style ranches he reported and considerable evidence, on the contrary, for the widespread survival of small-scale farms. It is not even certain that either war damage or the absence of young unmarried men abroad would have had the devastating, long-term effect that is often imagined. Most agricultural land recovers quickly from that kind of trauma, and there would have been plenty of other family members to recruit to the workforce; and even if not, a few slave labourers would have been within the means of even relatively humble farmers. In fact, many historians now think that, if his motives were sincere, Tiberius seriously misread the situation.

Note: Had me in the first half, not gonna lie. It played right into my political biases and I was completely on board until the author revealed evidence to the contrary.

Page 187

The clash in 133 BCE revealed dramatically different views of the power of the people. When Tiberius persuaded them to vote out of office the tribune who opposed him, his argument went along the lines of ‘if the people’s tribune no longer does what the people want, then he should be deposed’. That raised an issue still familiar in modern electoral systems. Are Members of Parliament, for example, to be seen as delegates of the voters, bound to follow the will of their electorate? Or are they representatives, elected to exercise their own judgement in the changing circumstances of government? This was the first time, so far as we know, that this question had been explicitly raised in Rome, and it was no more easily answered then than it is now. For some, Tiberius’ actions vindicated the rights of the people; for others they undermined the rights of a properly elected official.

Page 201

But their argument with Tiberius was a fundamental one, which framed Roman political debate for the rest of the Republic. Cicero, looking back from the middle of the next century, could present 133 BCE as a decisive year precisely because it opened up a major fault line in Roman politics and society that was not closed again during his lifetime: ‘The death of Tiberius Gracchus,’ he wrote, ‘and even before that the whole rationale behind his tribunate, divided a united people into two distinct groups [partes].’ This is a rhetorical oversimplification. The idea that there had been a calm consensus at Rome between rich and poor until Tiberius Gracchus shattered it is at best a nostalgic fiction. It seems likely, from what is known of the political debates in the decade or so before 133 BCE (which is not much), that others had already asserted the rights of the people along much the same lines. In 139 BCE, for example, one radical tribune had introduced a law to ensure that Roman elections were conducted by secret ballot. There is little evidence to help flesh out the man behind this or to throw light on the opposition it must have aroused – though Cicero gives a hint when he says that ‘everyone knows that the ballot law robbed the aristocrats of all their influence’ and describes the proposer as ‘a filthy nobody’. But it was a milestone reform and a fundamental guarantee of political freedom for all citizens, and one that was unknown in elections in the classical Greek world, democratic or not. Nevertheless, it was the events of 133 BCE that crystallised the opposition between those who championed the rights, liberty and benefits of the people and those who, to put it in their own terms, thought it prudent for the state to be guided by the experience and wisdom of the ‘best men’ (optimi), who in practice were more or less synonymous with the rich. Cicero uses the word partes for these two groups (populares and optimates, as they were sometimes called), but they were not parties in the modern sense: they had no members, official leaders or agreed manifestos. They represented two sharply divergent views of the aims and methods of government, which were repeatedly to clash for almost a hundred years.

Note: I’m glad she calls out Cicero for obvious BS. I feel like historians are often too deferential to contemporary sources.

Page 242

Charitable aims, however, were not the only thing in Gaius’ mind, nor even the hard-headed logic, sometimes in evidence at Rome, that a hungry populace was a dangerous one. His plan also had an underlying political agenda about the sharing of the state’s resources. That certainly is the point of a reported exchange between Gaius and one of his most implacable opponents, the wealthy ex-consul Lucius Calpurnius Piso Frugi (his last name, appropriately enough, means ‘stingy’). After the law had been passed, Gaius spotted Frugi standing in line for his allocation of grain and asked him why he was there, since he so disapproved of the measure. ‘I’m not keen, Gracchus,’ he replied, ‘on you getting the idea of sharing out my property man by man, but if that’s what you’re going to do, I’ll take my cut.’ He was presumably turning Gaius’ rhetoric back on him. The debate was about who had a claim on the property of the state and where the boundary lay between private and public wealth.

Note: Ayn Rand’s ancestor

Page 286

In response, the senate passed a decree urging the consuls ‘to make sure that the state should come to no harm’, the same emergency powers act as was later passed during Cicero’s clash with Catiline in 63 BCE. Opimius took the cue, gathered together an amateur militia of his supporters and put some 3,000 Gracchans to death, either on the spot or later in an impromptu court. It established a dubious and deadly precedent. For this was the first occasion of several over the next hundred years when this decree was used to confront various crises, from civil disorder to alleged treason. It may have been devised as an attempt to put some kind of regulatory framework on the use of official force. Rome at this period had no police of any kind and hardly any resources for controlling violence beyond what individual powerful men could scratch together. The instruction ‘to make sure that the state should come to no harm’ could in theory have been intended to draw a line between the unauthorised actions of a Scipio Nasica and those sanctioned by the senate. In practice, it was a lynch mob’s charter, a partisan excuse to suspend civil liberties and a legal fig leaf for premeditated violence against radical reformers. It is, for example, hard to believe that the ‘Cretan archers’ who joined Opimius’ local supporters were on hand purely by chance. But the decree was always controversial and always liable to rebound, as Cicero discovered. Opimius was duly put on trial, and though he was acquitted, his reputation never entirely recovered. When he had the nerve, or naivety, to celebrate his suppression of the Gracchans by lavishly restoring the temple of the goddess Concord (‘Harmony’) in the Forum, some realist with a chisel summed up the whole murderous debacle by carving across the façade the words ‘An act of senseless Discord produces a Temple of Concord’.

Page 310

It ended with many of the allies going to war on Rome in the Social War, one of the deadliest and most puzzling conflicts in Roman history. The puzzle turns largely on what the aims of the allies were. Did they resort to violence to force Rome to grant them full Roman citizenship? Or were they trying to shake themselves free of Rome? Did they want in or out?

Note: Really strange we don’t know that.

Page 341

sense of political exclusion, and second-class status, on the part of leading allies. The senate began to take it for granted that it could lay down the law for the whole of Italy. Tiberius Gracchus’ land reform, popular as it might have been to poor Romans, was a provocation to rich Italians whose ‘public land’ was removed, while excluding poor Italians from the distributions. The close personal relationships that some of the Italian elite had with leading Romans (how else did they enlist Scipio Aemilianus’ help against Tiberius’ land reform?) did not make up for the fact that they had no formal stake in Roman politics or decision-making.

Note: I understand why Tiberius did that, but still, doesn’t look good by 21st century standards.

Page 349

At the same time, in Rome, fears about outsiders flooding into the city were whipped up in a way familiar from many modern campaigns of xenophobia. One of Gaius’ opponents, addressing a contio, or public meeting, conjured up visions of Romans being swamped. ‘Once you have given citizenship to the Latins,’ he urged his audience, ‘I mean, do you think there will be any space for you, like there is now, in a contio or at games or festivals? Don’t you realise they’ll take over everything?’

Note: Ahhhh, so familiar

Page 374

For the contemporary propaganda and organisation of the Italian side suggest that it was actually a breakaway movement, aiming at total independence from Rome. The allies seem to have gone some way towards establishing a rival state, under the name ‘Italia’, with a capital at a town renamed ‘Italica’ and even the word Itali (‘Italians’) stamped on their lead shots. They minted coins displaying a memorable image of a bull, the symbol of Italy, goring a wolf, the symbol of Rome. And one of the Italian leaders neatly turned the story of Romulus and Remus on its head by dubbing the Romans ‘the wolves who have ravished Italian liberty’. That does not look like a plea for integration.

Page 384

Whatever the causes of the Social War, the effects of the legislation of 90 and 89 BCE that extended full citizenship to most of the peninsula were dramatic. Italy was now the closest thing to a nation state that the classical world ever knew, and the principle we glimpsed centuries earlier that ‘Romans’ could have dual citizenship and two civic identities, that of Rome and that of their home town, became the norm. If the figures reported by ancient writers are at all accurate, the number of Roman citizens increased at a stroke by about threefold, to something over a million.

Note: Closest to a nation state

Page 418