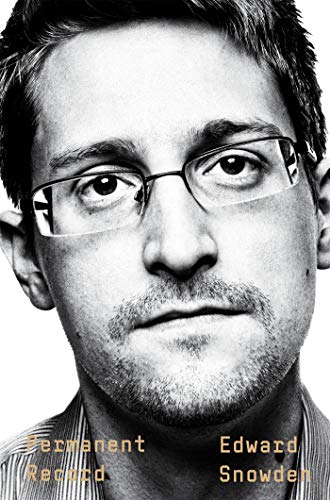

Permanent Record

by Edward Snowden

- Author:

- Edward Snowden

- Status:

- Done

- Format:

- eBook

- Reading Time:

- 10:16

- Genres:

- Nonfiction , Biography , Politics , Memoir , History , Technology

- Pages:

- 339

- Highlights:

- 85

Highlights

Page 1

After 9/11, the IC was racked with guilt for failing to protect America, for letting the most devastating and destructive attack on the country since Pearl Harbor occur on its watch. In response, its leaders sought to build a system that would prevent them from being caught off guard ever again.

Page 3

Deep in a tunnel under a pineapple field—a subterranean Pearl Harbor–era former airplane factory—I sat at a terminal from which I had practically unlimited access to the communications of nearly every man, woman, and child on earth who’d ever dialed a phone or touched a computer. Among those people were about 320 million of my fellow American citizens, who in the regular conduct of their everyday lives were being surveilled in gross contravention of not just the Constitution of the United States, but the basic values of any free society.

Page 4

when I came to know it, the Internet was a very different thing. It was a friend, and a parent. It was a community without border or limit, one voice and millions, a common frontier that had been settled but not exploited by diverse tribes living amicably enough side by side, each member of which was free to choose their own name and history and customs. Everyone wore masks, and yet this culture of anonymity-through-polyonymy produced more truth than falsehood, because it was creative and cooperative rather than commercial and competitive. Certainly, there was conflict, but it was outweighed by goodwill and good feelings—the true pioneering spirit.

Note: Anonymity through polyanonymy

Page 5

The successors to the e-commerce companies that had failed because they couldn’t find anything we were interested in buying now had a new product to sell. That new product was Us.

Note: I feel defensive when I read this because I’m employed by fb. It’s possible that he is right but I get the feeling that government surveillance and corporate collection of data are two separate things. Especially since fb is bending over backwards to get encrypted messaging to everyone.

Page 6

The system of near-universal surveillance had been set up not just without our consent, but in a way that deliberately hid every aspect of its programs from our knowledge.

Page 6

The freedom of a country can only be measured by its respect for the rights of its citizens, and it’s my conviction that these rights are in fact limitations of state power that define exactly where and when a government may not infringe into that domain of personal or individual freedoms that during the American Revolution was called “liberty” and during the Internet Revolution is called “privacy.”

Page 7

I know this process intimately enough, because the creation of irreality has always been the Intelligence Community’s darkest art. The same agencies that, over the span of my career alone, had manipulated intelligence to create a pretext for war—and used illegal policies and a shadow judiciary to permit kidnapping as “extraordinary rendition,” torture as “enhanced interrogation,” and mass surveillance as “bulk collection”—didn’t hesitate for a moment to call me a Chinese double agent, a Russian triple agent, and worse: “a millennial.”

Note: Love his sense of humour

Page 28

Like all my father’s lessons, this one had broad applications beyond our immediate task. Ultimately, it was a lesson in the principle of self-reliance, which my father insisted that America had forgotten sometime between his own childhood and mine. Ours was now a country in which the cost of replacing a broken machine with a newer model was typically lower than the cost of having it fixed by an expert, which itself was typically lower than the cost of sourcing the parts and figuring out how to fix it yourself. This fact alone virtually guaranteed technological tyranny, which was perpetuated not by the technology itself but by the ignorance of everyone who used it daily and yet failed to understand it. To refuse to inform yourself about the basic operation and maintenance of the equipment you depended on was to passively accept that tyranny and agree to its terms: when your equipment works, you’ll work, but when your equipment breaks down you’ll break down, too. Your possessions would possess you.

Page 37

My father’s career remains fairly opaque to me to this day, and the fact is that my ignorance here isn’t anomalous. In the world I grew up in, nobody really talked about their jobs—not just to children, but to each other. It is true that many of the adults around me were legally prohibited from discussing their work, even with their families, but to my mind a more accurate explanation lies in the technical nature of their labor and the government’s insistence on compartmentalization. Tech people rarely, if ever, have a sense of the broader applications and policy implications of the projects to which they’re assigned. And the work that consumes them tends to require such specialized knowledge that to bring it up at a barbecue would get them disinvited from the next one, because nobody cared. In retrospect, maybe that’s what got us here.

Page 43

I couldn’t bear to have those privileges revoked, disturbed by the thought that every moment that I wasn’t online more and more material was appearing that I’d be missing. After repeated parental warnings and threats of grounding, I’d finally relent and print out whatever file I was reading and bring the dot-matrix pages up to bed. I’d continue studying in hard copy until my parents had gone to bed themselves, and then I’d tiptoe out into the dark, wary of the squeaky door and the creaky floorboards by the stairs. I’d keep the lights off and, guiding myself by the glow of the screen saver, I’d wake the computer up and go online, holding my pillows against the machine to stifle the dial tone of the modem and the ever-intensifying hiss of its connection.

Note: Hahaha. So relatable and at the same time I’m thinking “wow he needs help”

Page 45

Once, a certain BBS that I was on tried to coordinate casual in-the-flesh meetings of its regular members throughout the country: in DC, in New York, at the Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas. After being pressured rather hard to attend—and promised extravagant evenings of eating and drinking—I finally just told everyone how old I was. I was afraid that some of my correspondents might stop interacting with me, but instead they became, if anything, even more encouraging. I was sent updates from the electronics show and images of its catalog; one guy offered to ship me secondhand computer parts through the mail, free of charge.

Note: That’s so sweet

Page 51

All teenagers are hackers. They have to be, if only because their life circumstances are untenable. They think they’re adults, but the adults think they’re kids. Remember, if you can, your own teen years. You were a hacker, too, willing to do anything to evade parental supervision. Basically, you were fed up with being treated like a child. Recall how it felt when anyone older and bigger than you sought to control you, as if age and size were identical with authority. At one time or another, your parents, teachers, coaches, scoutmasters, and clergy would all take advantage of their position to invade your private life, impose their expectations on your future, and enforce your conformity to past standards. Whenever these adults substituted their hopes, dreams, and desires for your own, they were doing so, by their account, “for your own good” or “with your best interests at heart.” And while sometimes this was true, we all remember those other times when it wasn’t—when “because I said so” wasn’t enough and “you’ll thank me one day” rang hollow. If you’ve ever been an adolescent, you’ve surely been on the receiving end of one of these clichés, and so on the losing end of an imbalance of power. To grow up is to realize the extent to which your existence has been governed by systems of rules, vague guidelines, and increasingly unsupportable norms that have been imposed on you without your consent and are subject to change at a moment’s notice. There were even some rules that you’d only find out about after you’d violated them.

Note: well put

Page 52

That, ultimately, is the critical flaw or design defect intentionally integrated into every system, in both politics and computing: the people who create the rules have no incentive to act against themselves.

Note: yesssss

Page 60

“Not at all,” the IT rep said, and then asked what I did for a living. “Nothing really,” I said. He asked whether I was looking for a job and I said, “During the school year, I’m pretty busy, but I’ve got a lot of vacation and the summers are free.” That’s when the lightbulb went off, and he realized that he was dealing with a teenager. “Well, kid,” he said, “you’ve got my contact. Be sure and get in touch when you turn eighteen. Now pass me along to that nice lady I spoke to.” I handed the phone to my anxious mother and she took it back with her into the kitchen, which was filling up with smoke. Dinner was burnt, but I’m guessing the IT rep said enough complimentary things about me that any punishment I was imagining went out the window.

Note: nothing really lmfao… like hes retired after vesting

Page 62

When I was a teen, I think I was a touch too enamored of the idea that life’s most important questions are binary, meaning that one answer is always Right, and all the rest of the answers are Wrong. I think I was enchanted by the model of computer programming, whose questions can only be answered in one of two ways: 1 or 0, the machine-code version of Yes or No, True or False.

Note: same problem here

Page 67

This kind of change is constant, common, and human. But an autobiographical statement is static, the fixed document of a person in flux. This is why the best account that someone can ever give of themselves is not a statement but a pledge—a pledge to the principles they value, and to the vision of the person they hope to become.

Page 69

This, by the way, is the best way to “seem normal”: surround yourself with people just as weird, if not weirder, than you are. Most of these friends were aspiring artists and graphic designers obsessed with then controversial anime, or Japanese animation. As our friendships deepened, so, too, did my familiarity with anime genres, until I could rattle off relatively informed opinions about a new library of shared experiences with titles like Grave of the Fireflies, Revolutionary Girl Utena, Neon Genesis Evangelion, Cowboy Bebop, The Vision of Escaflowne, Rurouni Kenshin, Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, Trigun, The Slayers, and my personal favorite, Ghost in the Shell.

Note: great taste. truly a man of culture

Page 80

America immediately divided the world into “Us” and “Them,” and everyone was either with “Us” or against “Us,” as President Bush so memorably remarked even while the rubble was still smoldering. People in my neighborhood put up new American flags, as if to show which side they’d chosen. People hoarded red, white, and blue Dixie cups and stuffed them through every chain-link fence on every overpass of every highway between my mother’s home and my father’s, to spell out phrases like UNITED WE STAND and STAND TOGETHER NEVER FORGET. I sometimes used to go to a shooting range and now alongside the old targets, the bull’s-eyes and flat silhouettes, were effigies of men in Arab headdress. Guns that had languished for years behind the dusty glass of the display cases were now marked SOLD. Americans also lined up to buy cell phones, hoping for advance warning of the next attack, or at least the ability to say good-bye from a hijacked flight.

Note: They changed.

Page 80

Nearly a hundred thousand spies returned to work at the agencies with the knowledge that they’d failed at their primary job, which was protecting America. Think of the guilt they were feeling. They had the same anger as everybody else, but they also felt the guilt. An assessment of their mistakes could wait. What mattered most at that moment was that they redeem themselves. Meanwhile, their bosses got busy campaigning for extraordinary budgets and extraordinary powers, leveraging the threat of terror to expand their capabilities and mandates beyond the imagination not just of the public but even of those who stamped the approvals.

Note: This guilt is the primary driving force even today.

Page 81

September 12 was the first day of a new era, which America faced with a unified resolve, strengthened by a revived sense of patriotism and the goodwill and sympathy of the world. In retrospect, my country could have done so much with this opportunity. It could have treated terror not as the theological phenomenon it purported to be, but as the crime it was. It could have used this rare moment of solidarity to reinforce democratic values and cultivate resilience in the now-connected global public.

Note: This is far fetched. I don’t think any leader would do any different from what George Bush did.

Page 81

The greatest regret of my life is my reflexive, unquestioning support for that decision. I was outraged, yes, but that was only the beginning of a process in which my heart completely defeated my rational judgment. I accepted all the claims retailed by the media as facts, and I repeated them as if I were being paid for it. I wanted to be a liberator. I wanted to free the oppressed. I embraced the truth constructed for the good of the state, which in my passion I confused with the good of the country. It was as if whatever individual politics I’d developed had crashed—the anti-institutional hacker ethos instilled in me online, and the apolitical patriotism I’d inherited from my parents, both wiped from my system—and I’d been rebooted as a willing vehicle of vengeance. The sharpest part of the humiliation comes from acknowledging how easy this transformation was, and how readily I welcomed it.

Note: The state is not the country. That insight eludes Indian people

Page 92

As I held the statement in one hand and the pen in the other, a knowing smile crossed my face. I recognized the hack: what I’d thought was a kind and generous offer made by a caring army doctor to an ailing enlistee was the government’s way of avoiding liability and a disability claim. Under the military’s rules, if I’d received a medical discharge, the government would have had to pay the bills for any issues stemming from my injury, any treatments and therapies it required. An administrative discharge put the burden on me, and my freedom hinged on my willingness to accept that burden. I signed, and left that same day, on crutches that the army let me keep.

Page 95

I mean, I grew up on the Internet, for Christ’s sake. If you haven’t entered something shameful or gross into that search box, then you haven’t been online very long—though I wasn’t worried about the pornography. Everybody looks at porn, and for those of you who are shaking your heads, don’t worry: your secret is safe with me. My worries were more personal, or felt more personal: the endless conveyor belt of stupid jingoistic things I’d said, and the even stupider misanthropic opinions I’d abandoned, in the process of growing up online. Specifically, I was worried about my chat logs and forum posts, all the supremely moronic commentary that I’d sprayed across a score of gaming and hacker sites. Writing pseudonymously had meant writing freely, but often thoughtlessly. And since a major aspect of early Internet culture was competing with others to say the most inflammatory thing, I’d never hesitate to advocate, say, bombing a country that taxed video games, or corralling people who didn’t like anime into reeducation camps. Nobody on those sites took any of it seriously, least of all myself.

Note: Anime re-education lmao

Page 97

My situation was somewhat different, however, in that most of the message boards of my day would let you delete your old posts. I could put together one tiny little script—not even a real program—and all of my posts would be gone in under an hour. It would’ve been the easiest thing in the world to do. Trust me, I considered it. But ultimately, I couldn’t. Something kept preventing me. It just felt wrong. To blank my posts from the face of the earth wasn’t illegal, and it wouldn’t even have made me ineligible for a security clearance had anyone found out. But the prospect of doing so bothered me nonetheless. It would’ve only served to reinforce some of the most corrosive precepts of online life: that nobody is ever allowed to make a mistake, and anybody who does make a mistake must answer for it forever. What mattered to me wasn’t so much the integrity of the written record but that of my soul. I didn’t want to live in a world where everyone had to pretend that they were perfect, because that was a world that had no place for me or my friends. To erase those comments would have been to erase who I was, where I was from, and how far I’d come. To deny my younger self would have been to deny my present self’s validity.

Note: Wise

Page 100

I told her everything, too, including the fact that I wouldn’t be able to talk to her about my work—the work I hadn’t even started. This was ludicrously pretentious, which she made obvious to me by nodding gravely.

Page 105

I’m going to press Pause here, for a moment, to explain something about my politics at age twenty-two: I didn’t have any. Instead, like most young people, I had solid convictions that I refused to accept weren’t truly mine but rather a contradictory cluster of inherited principles. My mind was a mash-up of the values I was raised with and the ideals I encountered online. It took me until my late twenties to finally understand that so much of what I believed, or of what I thought I believed, was just youthful imprinting. We learn to speak by imitating the speech of the adults around us, and in the process of that learning we wind up also imitating their opinions, until we’ve deluded ourselves into thinking that the words we’re using are our own.

Note: So true it hurts. Even now I don’t know if my ideas are my own or not.

Page 106

These were also the people who, when their country went to war, answered the call. That’s what I had done after 9/11, and I found that the patriotism my parents had taught me was easily converted into nationalist fervor. For a time, especially in my run-up to joining the army, my sense of the world came to resemble the duality of the least sophisticated video games, where good and evil are clearly defined and unquestionable.

Note: We need a black and white sense of good and evil so much that we create it where it doesn’t exist.

Page 108

I thought about this a lot while I was driving, to and from Lindsay’s house and to and from AACC. Car time has always been thinking time for me, and commutes are long on the crowded Beltway. To be a software developer was to run the rest stops off the exits and to make sure that all the fast-food and gas station franchises accorded with each other and with user expectations; to be a hardware specialist was to lay the infrastructure, to grade and pave the roads themselves; while to be a network specialist was to be responsible for traffic control, manipulating signs and lights to safely route the time-crunched hordes to their proper destinations. To get into systems, however, was to be an urban planner, to take all of the components available and ensure their interaction to maximum effect. It was, pure and simple, like getting paid to play God, or at least a tinpot dictator.

Note: Good analogy

Page 112

These sensationalist cases can lead the public to believe that the government employs contractors in order to maintain cover and deniability, off-loading the illegal or quasi-legal dirty work to keep its hands clean and conscience clear. But that’s not entirely true, or at least not entirely true in the IC, which tends to focus less on deniability and more on never getting caught in the first place. Instead, the primary purpose served by IC contracting is much more mundane: it’s a workaround, a loophole, a hack that lets agencies circumvent federal caps on hiring. Every agency has a head count, a legislative limit that dictates the number of people it can hire to do a certain type of work. But contractors, because they’re not directly employed by the federal government, aren’t included in that number. The agencies can hire as many of them as they can pay for, and they can pay for as many of them as they want—all they have to do is testify to a few select congressional subcommittees that the terrorists are coming for our children, or the Russians are in our emails, or the Chinese are in our power grid. Congress never says no to this type of begging, which is actually a kind of threat, and reliably capitulates to the IC’s demands.

Page 113

To be sure, there are many, even in government, who maintain that this trickle-down scheme is advantageous. With contractors, they say, the government can encourage competitive bidding to keep costs down, and isn’t on the hook to pay pensions and benefits. But the real advantage for government officials is the conflict of interest inherent in the budgeting process itself. IC directors ask Congress for money to rent contract workers from private companies, congresspeople approve that money, and then those IC directors and congresspeople are rewarded, after they retire from office, by being given high-paying positions and consultancies with the very companies they’ve just enriched. From the vantage of the corporate boardroom, contracting functions as governmentally assisted corruption. It’s America’s most legal and convenient method of transferring public money to the private purse.

Note: Succinct.

Page 115

At the time I was still naive enough to think that my position with CASL would be a bridge to a full-time federal career. But the more I looked around, the more I was amazed to find that there were very few opportunities to serve my country directly, at least in a meaningful technical role. I had a better chance of working as a contractor for a private company that served my country for profit; and I had the best chance, it turned out, of working as a subcontractor for a private company that contracted with another private company that served my country for profit. The realization was dizzying. It was particularly bizarre to me that most of the systems engineering and systems administration jobs that were out there were private, because these positions came with almost universal access to the employer’s digital existence. It’s unimaginable that a major bank or even a social media outfit would hire outsiders for systems-level work. In the context of the US government, however, restructuring your intelligence agencies so that your most sensitive systems were being run by somebody who didn’t really work for you was what passed for innovation.

Note: “What passed for innovation” - stinging rebuke

Page 121

“So this is the Deep State,” one guy said, and almost everybody laughed. I think he’d been expecting a circle of Ivy League WASPs chanting in hoods, whereas I’d been expecting a group of normie civil service types who resembled younger versions of my parents. Instead, we were all computer dudes—and yes, almost uniformly dudes—who were clearly wearing “business casual” for the first time in our lives. Some were tattooed and pierced, or bore evidence of having removed their piercings for the big day. One still had punky streaks of dye in his hair. Almost all wore contractor badges, as green and crisp as new hundred-dollar bills. We certainly didn’t look like a hermetic power-mad cabal that controlled the actions of America’s elected officials from shadowy subterranean cubicles.

Page 133

The higher up this employee is, and the more systems-level privileges he has, the more access he has to virtually every byte of his employer’s digital existence. Of course, not everyone is curious enough to take advantage of this education, and not everyone is possessed of a sincere curiosity. My forays through the CIA’s systems were natural extensions of my childhood desire to understand how everything works, how the various components of a mechanism fit together into the whole. And with the official title and privileges of a systems administrator, and technical prowess that enabled my clearance to be used to its maximum potential, I was able to satisfy my every informational deficiency and then some. In case you were wondering: Yes, man really did land on the moon. Climate change is real. Chemtrails are not a thing.

Note: Disappointed that he’s spreading these hoaxes

Page 140

Why this was a job for the CIA and not for the State Department—the entity that actually owns the embassy building—is more than the sheer difference in competence and trust: the real reason is plausible deniability. The worst-kept secret in modern diplomacy is that the primary function of an embassy nowadays is to serve as a platform for espionage. The old explanations for why a country might try to maintain a notionally sovereign physical presence on another country’s soil faded into obsolescence with the rise of electronic communications and jet-powered aircraft. Today, the most meaningful diplomacy happens directly between ministries and ministers. Sure, embassies do still send the occasional démarche and help support their citizens abroad, and then there are the consular sections that issue visas and renew passports. But those are often in a completely different building, and anyway, none of those activities can even remotely justify the expense of maintaining all that infrastructure. Instead, what justifies the expense is the ability for a country to use the cover of its foreign service to conduct and legitimize its spying.

Page 145

He’d been at the agency longer than any of my other classmates; he knew how it worked, and how ludicrous it was to trust management to fix something that management itself had broken. I was a bureaucratic innocent by comparison, disturbed by the loss and by the ease with which Spo and the others accepted it. I hated the feeling that the mere fiction of process was enough to dispel a genuine demand for results. It wasn’t that my classmates didn’t care enough to fight, it was that they couldn’t afford to: the system was designed so that the perceived cost of escalation exceeded the expected benefit of resolution. At age twenty-four, though, I thought as little of the costs as I did of the benefits; I just cared about the system. I wasn’t finished.

Page 156

This layering method is called onion routing, which gives Tor its name: it’s The Onion Router. The classified joke was that trying to surveil the Tor network makes spies want to cry. Therein lies the project’s irony: here was a US military–developed technology that made cyberintelligence simultaneously harder and easier, applying hacker know-how to protect the anonymity of IC officers, but only at the price of granting that same anonymity to adversaries and to average users across the globe. In this sense, Tor was even more neutral than Switzerland. For me personally, Tor was a life changer, bringing me back to the Internet of my childhood by giving me just the slightest taste of freedom from being observed.

Page 157

Sitting around discussing how to hack a faceless UN complex was psychologically easier by a wide margin. Direct engagement, which can be harsh and emotionally draining, simply doesn’t happen that much on the technical side of intelligence, and almost never in computing. There is a depersonalization of experience fostered by the distance of a screen. Peering at life through a window can ultimately abstract us from our actions and limit any meaningful confrontation with their consequences.

Page 157

As a technologist, I found it incredibly easy to defend my cover. The moment some bespoke-suited cosmopolite asked me what I did, and I responded with the four words “I work in IT” (or, in my improving French, je travaille dans l’informatique), their interest in me was over. Not that this ever stopped the conversation. When you’re a fresh-faced professional in a conversation outside your field, it’s never that surprising when you ask a lot of questions, and in my experience most people will jump at the chance to explain exactly how much more they know than you do about something they care about deeply.

Note: This is more nuanced than what I say - “people love talking about themselves “

Page 160

Too much had been hazarded, too little had been gained. It was a waste, which I myself had put in motion and then was powerless to stop. After that experience, the prioritizing of SIGINT over HUMINT made all the more sense to me.

Page 162

To live in Geneva was to live in an alternative, even opposite, reality. As the rest of the world became more and more impoverished, Geneva flourished, and while the Swiss banks didn’t engage in many of the types of risky trades that caused the crash, they gladly hid the money of those who’d profited from the pain and were never held accountable. The 2008 crisis, which laid so much of the foundation for the crises of populism that a decade later would sweep across Europe and America, helped me realize that something that is devastating for the public can be, and often is, beneficial to the elites. This was a lesson that the US government would confirm for me in other contexts, time and again, in the years ahead.

Page 164

Given the American nature of the planet’s communications infrastructure, it should have been obvious that the US government would engage in this type of mass surveillance. It should have been especially obvious to me. Yet it wasn’t—mostly because the government kept insisting that it did nothing of the sort, and generally disclaimed the practice in courts and in the media in a manner so adamant that the few remaining skeptics who accused it of lying were treated like wild-haired conspiracy junkies. Their suspicions about secret NSA programs seemed hardly different from paranoid delusions involving alien messages being beamed to the radios in our teeth. We—me, you, all of us—were too trusting. But what makes this all the more personally painful for me was that the last time I’d made this mistake, I’d supported the invasion of Iraq and joined the army. When I arrived in the IC, I felt sure that I’d never be fooled again, especially given my top secret clearance. Surely that had to count for some degree of transparency. After all, why would the government keep secrets from its secret keepers? This is all to say that the obvious didn’t even become the thinkable for me until some time after I moved to Japan in 2009 to work for the NSA, America’s premier signals intelligence agency.

Note: Easy to forget that before Snowden all of us thought this

Page 177

Such fraudulent redefinitions ran throughout the report, but perhaps the most fundamental and transparently desperate involved the government’s vocabulary. STELLARWIND had been collecting communications since the PSP’s inception in 2001, but in 2004—when Justice Department officials balked at the continuation of the initiative—the Bush administration attempted to legitimize it ex post facto by changing the meanings of basic English words, such as “acquire” and “obtain.” According to the report, it was the government’s position that the NSA could collect whatever communications records it wanted to, without having to get a warrant, because it could only be said to have acquired or obtained them, in the legal sense, if and when the agency “searched for and retrieved” them from its database. This lexical sophistry was particularly galling to me, as I was well aware that the agency’s goal was to be able to retain as much data as it could for as long as it could—for perpetuity. If communications records would only be considered definitively “obtained” once they were used, they could remain “unobtained” but collected in storage forever, raw data awaiting its future manipulation. By redefining the terms “acquire” and “obtain”—from describing the act of data being entered into a database, to describing the act of a person (or, more likely, an algorithm) querying that database and getting a “hit” or “return” at any conceivable point in the future—the US government was developing the capacity of an eternal law-enforcement agency. At any time, the government could dig through the past communications of anyone it wanted to victimize in search of a crime (and everybody’s communications contain evidence of something). At any point, for all perpetuity, any new administration—any future rogue head of the NSA—could just show up to work and, as easily as flicking a switch, instantly track everybody with a phone or a computer, know who they were, where they were, what they were doing with whom, and what they had ever done in the past.

Note: The next level play. Once you redefine words, you can do anything.

Page 180

One major irony here is that law, which always lags behind technological innovation by at least a generation, gives substantially more protections to a communication’s content than to its metadata—and yet intelligence agencies are far more interested in the metadata—the activity records that allow them both the “big picture” ability to analyze data at scale, and the “little picture” ability to make perfect maps, chronologies, and associative synopses of an individual person’s life, from which they presume to extrapolate predictions of behavior. In sum, metadata can tell your surveillant virtually everything they’d ever want or need to know about you, except what’s actually going on inside your head.

Page 182

Technology doesn’t have a Hippocratic oath. So many decisions that have been made by technologists in academia, industry, the military, and government since at least the Industrial Revolution have been made on the basis of “can we,” not “should we.” And the intention driving a technology’s invention rarely, if ever, limits its application and use.

Note: JeffGoldblum.jpg

Page 183

A single current-model smartphone commands more computing power than all of the wartime machinery of the Reich and the Soviet Union combined. Recalling this is the surest way to contextualize not just the modern American IC’s technological dominance, but also the threat it poses to democratic governance. In the century or so since those census efforts, technology has made astounding progress, but the same could not be said for the law or human scruples that could restrain it.

Page 186

Once the ubiquity of collection was combined with the permanency of storage, all any government had to do was select a person or a group to scapegoat and go searching—as I’d gone searching through the agency’s files—for evidence of a suitable crime.

Page 196

Such a world of total automated law enforcement—of, say, all pet-ownership laws, or all zoning laws regulating home businesses—would be intolerable. Extreme justice can turn out to be extreme injustice, not just in terms of the severity of punishment for an infraction, but also in terms of how consistently and thoroughly the law is applied and prosecuted. Nearly every large and long-lived society is full of unwritten laws that everyone is expected to follow, along with vast libraries of written laws that no one is expected to follow, or even know about. According to Maryland Criminal Law Section 10-501, adultery is illegal and punishable by a $10 fine. In North Carolina, statute 14-309.8 makes it illegal for a bingo game to last more than five hours. Both of these laws come from a more prudish past and yet, for one reason or another, were never repealed. Most of our lives, even if we don’t realize it, occur not in black and white but in a gray area, where we jaywalk, put trash in the recycling bin and recyclables in the trash, ride our bicycles in the improper lane, and borrow a stranger’s Wi-Fi to download a book that we didn’t pay for. Put simply, a world in which every law is always enforced would be a world in which everyone was a criminal.

Note: Everyone is a criminal if you look hard enough

Page 204

Terrorism, of course, was the stated reason why most of my country’s surveillance programs were implemented, at a time of great fear and opportunism. But it turned out that fear was the true terrorism, perpetrated by a political system that was increasingly willing to use practically any justification to authorize the use of force. American politicians weren’t as afraid of terror as they were of seeming weak, or of being disloyal to their party, or of being disloyal to their campaign donors, who had ample appetites for government contracts and petroleum products from the Middle East. The politics of terror became more powerful than the terror itself, resulting in “counterterror”: the panicked actions of a country unmatched in capability, unrestrained by policy, and blatantly unconcerned about upholding the rule of law. After 9/11, the IC’s orders had been “never again,” a mission that could never be accomplished. A decade later, it had become clear, to me at least, that the repeated evocations of terror by the political class were not a response to any specific threat or concern but a cynical attempt to turn terror into a permanent danger that required permanent vigilance enforced by unquestionable authority.

Page 206

In an authoritarian state, rights derive from the state and are granted to the people. In a free state, rights derive from the people and are granted to the state. In the former, people are subjects, who are only allowed to own property, pursue an education, work, pray, and speak because their government permits them to. In the latter, people are citizens, who agree to be governed in a covenant of consent that must be periodically renewed and is constitutionally revocable. It’s this clash, between the authoritarian and the liberal democratic, that I believe to be the major ideological conflict of my time—not some concocted, prejudiced notion of an East-West divide, or of a resurrected crusade against Christendom or Islam.

Page 207

Authoritarian states are typically not governments of laws, but governments of leaders, who demand loyalty from their subjects and are hostile to dissent. Liberal-democratic states, by contrast, make no or few such demands, but depend almost solely on each citizen voluntarily assuming the responsibility of protecting the freedoms of everyone else around them, regardless of their race, ethnicity, creed, ability, sexuality, or gender. Any collective guarantee, predicated not on blood but on assent, will wind up favoring egalitarianism—and though democracy has often fallen far short of its ideal, I still believe it to be the one form of governance that most fully enables people of different backgrounds to live together, equal before the law.

Page 208

There is, simply, no way to ignore privacy. Because a citizenry’s freedoms are interdependent, to surrender your own privacy is really to surrender everyone’s. You might choose to give it up out of convenience, or under the popular pretext that privacy is only required by those who have something to hide. But saying that you don’t need or want privacy because you have nothing to hide is to assume that no one should have, or could have, to hide anything—including their immigration status, unemployment history, financial history, and health records. You’re assuming that no one, including yourself, might object to revealing to anyone information about their religious beliefs, political affiliations, and sexual activities, as casually as some choose to reveal their movie and music tastes and reading preferences. Ultimately, saying that you don’t care about privacy because you have nothing to hide is no different from saying you don’t care about freedom of speech because you have nothing to say. Or that you don’t care about freedom of the press because you don’t like to read. Or that you don’t care about freedom of religion because you don’t believe in God. Or that you don’t care about the freedom to peaceably assemble because you’re a lazy, antisocial agoraphobe. Just because this or that freedom might not have meaning to you today doesn’t mean that it doesn’t or won’t have meaning tomorrow, to you, or to your neighbor—or to the crowds of principled dissidents I was following on my phone who were protesting halfway across the planet, hoping to gain just a fraction of the freedoms that my country was busily dismantling.

Page 224

The next stage of my investigation was to figure out how this collection was actually accomplished—that is to say, to examine the documents that explained which tools supported this program and how they selected from among the vast mass of dragneted communications those that were thought worthy of closer inspection. The difficulty was that this information did not exist in any presentation, no matter the level of classification, but only in engineering diagrams and raw schematics. These were the most important materials for me to find. Unlike the Five Eyes’ pitchdeck cant, they would be concrete proof that the capacities I was reading about weren’t merely the fantasies of an overcaffeinated project manager. As a systems guy who was always being prodded to build faster and deliver more, I was all too aware that the agencies would sometimes announce technologies before they even existed—sometimes because a Cliff-type salesperson had made one too many promises, and sometimes just out of unalloyed ambition.

Note: Haha. I can imagine such a PM

Page 225

You can think of TURMOIL as a guard positioned at an invisible firewall through which Internet traffic must pass. Seeing your request, it checks its metadata for selectors, or criteria, that mark it as deserving of more scrutiny. Those selectors can be whatever the NSA chooses, whatever the NSA finds suspicious: a particular email address, credit card, or phone number; the geographic origin or destination of your Internet activity; or just certain keywords such as “anonymous Internet proxy” or “protest.”

Note: Blows my mind. How do they implement this efficiently? What is the size of the cache that contains every identifier and every keyword?

Page 228

The Intelligence Community had always had an uncomfortable relationship with Constitution Day, which meant its involvement was typically limited to circulating a bland email drafted by its agencies’ press shops and signed by Director So-and-So, and setting up a sad little table in a forgotten corner of the cafeteria. On the table would be some free copies of the Constitution printed, bound, and donated to the government by the kind and generous rabble-rousers at places like the Cato Institute or the Heritage Foundation, since the IC was rarely interested in spending some of its own billions on promoting civil liberties through stapled paper.

Note: Lmao this guy is funny

Page 228

I liked reading the Constitution partially because its ideas are great, partially because its prose is good, but really because it freaked out my coworkers. In an office where everything you printed had to be thrown into a shredder after you were done with it, someone would always be intrigued by the presence of hardcopy pages lying on a desk. They’d amble over to ask, “What have you got there?” “The Constitution.” Then they’d make a face and back away slowly.

Note: Hahaha. He does the right things for the right reasons.

Page 228

Now, however, I read through it in its entirety, from the Articles to the Amendments. I was surprised to be reminded that fully 50 percent of the Bill of Rights, the document’s first ten amendments, were intended to make the job of law enforcement harder. The Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, Seventh, and Eighth Amendments were all deliberately, carefully designed to create inefficiencies and hamper the government’s ability to exercise its power and conduct surveillance. This is especially true of the Fourth, which protects people and their property from government scrutiny: The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized. Translation: If officers of the law want to go rooting through your life, they first have to go before a judge and show probable cause under oath. This means they have to explain to a judge why they have reason to believe that you might have committed a specific crime or that specific evidence of a specific crime might be found on or in a specific part of your property. Then they have to swear that this reason has been given honestly and in good faith. Only if the judge approves a warrant will they be allowed to go searching—and even then, only for a limited time. The Constitution was written in the eighteenth century, back when the only computers were abacuses, gear calculators, and looms, and it could take weeks or months for a communication to cross the ocean by ship. It stands to reason that computer files, whatever their contents, are our version of the Constitution’s “papers.” We certainly use them like “papers,” particularly our word-processing documents and spreadsheets, our messages and histories of inquiry. Data, meanwhile, is our version of “effects,” a catchall term for all the stuff that we own, produce, sell, and buy online. That includes, by default, metadata, which is the record of all the stuff that we own, produce, sell, and buy online—a perfect ledger of our private lives.

Note: Good, short explanation. Importantly, the Constitution makes collecting harder.

Page 230

The NSA’s surveillance programs, its domestic surveillance programs in particular, flouted the Fourth Amendment completely. The agency was essentially making a claim that the amendment’s protections didn’t apply to modern-day lives. The agency’s internal policies neither regarded your data as your legally protected personal property, nor regarded their collection of that data as a “search” or “seizure.” Instead, the NSA maintained that because you had already “shared” your phone records with a “third party”—your telephone service provider—you had forfeited any constitutional privacy interest you may once have had. And it insisted that “search” and “seizure” occurred only when its analysts, not its algorithms, actively queried what had already been automatically collected. Had constitutional oversight mechanisms been functioning properly, this…

Note: Clever lads.

Page 231

In early 2013, for instance, James Clapper, then the director of National Intelligence, testified under oath to the US Senate Select Committee on Intelligence that the NSA did not engage in bulk collection of the communications of American citizens. To the question, “Does the NSA collect any type of data at all on millions or hundreds of millions of Americans?” Clapper replied, “No, sir,” and then added, “There are cases where they could inadvertently perhaps collect, but not wittingly.” That was a witting, bald-faced lie, of course, not just to Congress but to the American people. More than a few of the congresspeople to whom Clapper was testifying knew very well that what he was saying was untrue, yet they refused, or felt legally powerless, to call him out on it.

Note: If no one will call you out on your shit, I guess you can continue shovelling it

Page 232

When civil society groups like the ACLU tried to challenge the NSA’s activities in ordinary, open federal courts, a curious thing happened. The government didn’t defend itself on the ground that the surveillance activities were legal or constitutional. It declared, instead, that the ACLU and its clients had no right to be in court at all, because the ACLU could not prove that its clients had in fact been surveilled. Moreover, the ACLU could not use the litigation to seek evidence of surveillance, because the existence (or nonexistence) of that evidence was “a state secret,” and leaks to journalists didn’t count. In other words, the court couldn’t recognize the information that was publicly known from having been published in the media; it could only recognize the information that the government officially confirmed as being publicly known. This invocation of classification meant that neither the ACLU, nor anyone else, could ever establish standing to raise a legal challenge in open court. To my disgust, in February 2013 the US Supreme Court decided 5 to 4 to accept the government’s reasoning and dismissed an ACLU and Amnesty International lawsuit challenging mass surveillance without even considering the legality of the NSA’s activities.

Note: The trickery is neat. Using standing to dismiss any concerns.

Page 234

The case was assigned to a judge appointed by Governor Hopkins, but before the trial commenced Shaw and Marven were saved by a fellow naval officer, John Grannis, who broke ranks and presented their case directly to the Continental Congress. The Continental Congress was so alarmed by the precedent being set by allowing military complaints regarding dereliction of duty to be subject to the criminal charge of libel that it intervened. On July 30, 1778, it terminated the command of Commodore Hopkins, ordered the Treasury Office to pay Shaw and Marven’s legal fees, and by unanimous consent enacted America’s first whistleblower protection law. This law declared it “the duty of all persons in the service of the United States, as well as all other inhabitants thereof, to give the earliest information to Congress or any other proper authority of any misconduct, frauds, or misdemeanors committed by any officers or persons in the service of these states, which may come to their knowledge.”

Page 236

Today, “leaking” and “whistleblowing” are often treated as interchangeable. But to my mind, the term “leaking” should be used differently than it commonly is. It should be used to describe acts of disclosure done not out of public interest but out of self-interest, or in pursuit of institutional or political aims. To be more precise, I understand a leak as something closer to a “plant,” or an incidence of “propaganda-seeding”: the selective release of protected information in order to sway popular opinion or affect the course of decision making. It is rare for even a day to go by in which some “unnamed” or “anonymous” senior government official does not leak, by way of a hint or tip to a journalist, some classified item that advances their own agenda or the efforts of their agency or party.

Note: Disagree partially. He draws a line between self interest and public interest as if they’re clearly different. But for those in public service, whether politicians or civil servants, there is no difference between the two. The people working at the NSA think a stronger NSA is good for America because if they didn’t, they’d work elsewhere. And that goes for any organisation.

So when they leak info to help their aims or causes, they sincerely believe that they’re working in the public interest.

Page 238

It’s only in this context that the US government’s latitudinal relationship to leaking can be fully understood. It has forgiven “unauthorized” leaks when they’ve resulted in unexpected benefits, and forgotten “authorized” leaks when they’ve caused harm. But if a leak’s harmfulness and lack of authorization, not to mention its essential illegality, make scant difference to the government’s reaction, what does? What makes one disclosure permissible, and another not? The answer is power. The answer is control. A disclosure is deemed acceptable only if it doesn’t challenge the fundamental prerogatives of an institution. If all the disparate components of an organization, from its mailroom to its executive suite, can be assumed to have the same power to discuss internal matters, then its executives have surrendered their information control, and the organization’s continued functioning is put in jeopardy. Seizing this equality of voice, independent of an organization’s managerial or decision-making hierarchy, is what is properly meant by the term “whistleblowing”—an act that’s particularly threatening to the IC, which operates by strict compartmentalization under a legally codified veil of secrecy.

Page 238

A “whistleblower,” in my definition, is a person who through hard experience has concluded that their life inside an institution has become incompatible with the principles developed in—and the loyalty owed to—the greater society outside it, to which that institution should be accountable. This person knows that they can’t remain inside the institution, and knows that the institution can’t or won’t be dismantled. Reforming the institution might be possible, however, so they blow the whistle and disclose the information to bring public pressure to bear.

Page 239

Whistleblowers can be elected by circumstance at any working level of an institution. But digital technology has brought us to an age in which, for the first time in recorded history, the most effective will come up from the bottom, from the ranks traditionally least incentivized to maintain the status quo. In the IC, as in virtually every other outsize decentralized institution that relies on computers, these lower ranks are rife with technologists like myself, whose legitimate access to vital infrastructure is grossly out of proportion to their formal authority to influence institutional decisions. In other words, there is usually an imbalance that obtains between what people like me are intended to know and what we are able to know, and between the slight power we have to change the institutional culture and the vast power we have to address our concerns to the culture at large. Though such technological privileges can certainly be abused—after all, most systems-level technologists have access to everything—the highest exercise of that privilege is in cases involving the technology itself.

Page 243

In retrospect, I have to credit at least some of my desire to find ideological filters to Lindsay’s improving influence. Lindsay had spent years patiently instilling in me the lesson that my interests and concerns weren’t always hers, and certainly weren’t always the world’s, and that just because I shared my knowledge didn’t mean that anyone had to share my opinion.

Note: Varsha does the same

Page 246

this lack

Page 248

Gus told the journalists that the agency could track their smartphones, even when they were turned off—that the agency could surveil every single one of their communications. Remember: this was a crowd of domestic journalists. American journalists. And the way that Gus said “could” came off as “has,” “does,” and “will.” He perorated in a distinctly disturbed, and disturbing, manner, at least for a CIA high priest: “Technology is moving faster than government or law can keep up. It’s moving faster … than you can keep up: you should be asking the question of what are your rights and who owns your data.” I was floored—anybody more junior than Gus who had given a presentation like this would’ve been wearing orange by the end of the day. Coverage of Gus’s confession ran only in the Huffington Post. But the performance itself lived on at YouTube, where it still remains, at least at the time of this writing six years later. The last time I checked, it had 313 views—a dozen of them mine.

Note: 313. People just aren’t interested.

Page 249

one of the capital crimes of intelligence work: whereas other spies have committed espionage, sedition, and treason, I would be aiding and abetting an act of journalism. The perverse fact is that legally, those crimes are virtually synonymous. American law makes no distinction between providing classified information to the press in the public interest and providing it, even selling it, to the enemy. The only opinion I’ve ever found to contradict this came from my first indoctrination into the IC: there, I was told that it was in fact slightly better to offer secrets for sale to the enemy than to offer them for free to a domestic reporter. A reporter will tell the public, whereas an enemy is unlikely to share its prize even with its allies.

Note: Haha

Page 258

Smartphones, of course, are banned in NSA buildings, but workers accidentally bring them in all the time without anyone noticing. They leave them in their gym bags or in the pockets of their windbreakers. If they’re caught with one in a random search and they act goofily abashed instead of screaming panicked mandarin into their wristwatch, they’re often merely warned, especially if it’s their first offense.

Note: Damn, screaming in Mandarin was my Plan A.

Page 262

I’d been careful not to leave any traces at my work, and I took care that my encryption left no traces of the documents at home. Still, I knew the documents could lead back to me once I’d sent them to the journalists and they’d been decrypted. Any investigator looking at which agency employees had accessed, or could access, all these materials would come up with a list with probably only a single name on it: mine. I could provide the journalists with fewer materials, of course, but then they wouldn’t be able to most effectively do their work. Ultimately, I had to contend with the fact that even one briefing slide or PDF left me vulnerable, because all digital files contain metadata, invisible tags that can be used to identify their origins. I struggled with how to handle this metadata situation. I worried that if I didn’t strip the identifying information from the documents, they might incriminate me the moment the journalists decrypted and opened them. But I also worried that by thoroughly stripping the metadata, I risked altering the files—if they were changed in any way, that could cast doubt on their authenticity. Which was more important: personal safety, or the public good? It might sound like an easy choice, but it took me quite a while to bite the bullet. I owned the risk, and left the metadata intact. Part of what convinced me was my fear that even if I had stripped away the metadata I knew about, there could be other digital watermarks I wasn’t aware of and couldn’t scan for. Another part had to do with the difficulty of scrubbing single-user documents. A single-user document is a document marked with a user-specific code, so that if any publication’s editorial staff decided to run it by the government, the government would know its source. Sometimes the unique identifier was hidden in the date and time-stamp coding, sometimes it involved the pattern of microdots in a graphic or logo. But it might also be embedded in something, in some way, I hadn’t even thought of. This phenomenon should have discouraged me, but instead it emboldened me. The technological difficulty forced me, for the first time, to confront the prospect of discarding my lifetime practice of anonymity and coming forward to identify myself as the source. I would embrace my principles by signing my name to them and let myself be condemned.

Note: The dangers are analyses well. But what courage to make that decision.

Page 280

I realized, as one of them was explaining to me the details of his targets’ security routines, that intercepted nudes were a kind of informal office currency, because his buddy kept spinning in his chair to interrupt us with a smile, saying, “Check her out,” to which my instructor would invariably reply “Bonus!” or “Nice!” The unspoken transactional rule seemed to be that if you found a naked photo or video of an attractive target—or someone in communication with a target—you had to show the rest of the boys, at least as long as there weren’t any women around. That was how you knew you could trust each other: you had shared in one another’s crimes.

Page 284

The process of elimination left me with Hong Kong. In geopolitical terms, it was the closest I could get to no-man’s-land, but with a vibrant media and protest culture, not to mention largely unfiltered Internet. It was an oddity, a reasonably liberal world city whose nominal autonomy would distance me from China and restrain Beijing’s ability to take public action against me or the journalists—at least immediately—but whose de facto existence in Beijing’s sphere of influence would reduce the possibility of unilateral US intervention. In a situation with no promise of safety, it was enough to have the guarantee of time. Chances were that things weren’t going to end well for me, anyway: the best I could hope for was getting the disclosures out before I was caught.

Note: Vibrant media BibleThump

Page 289

AT LONG LAST, Glenn and Laura showed up in Hong Kong on June 2. When they came to meet me at the Mira, I think I disappointed them, at least initially. They even told me as much, or Glenn did: He’d been expecting someone older, some chain-smoking, tipsy depressive with terminal cancer and a guilty conscience. He didn’t understand how a person as young as I was—he kept asking me my age—not only had access to such sensitive documents, but was also so willing to throw his life away.

Note: Too many spy novels Glenn

Page 292

As the revelations ran wall to wall on every TV channel and website, it became clear that the US government had thrown the whole of its machinery into identifying the source. It was also clear that when they did, they would use the face they found—my face—to evade accountability: instead of addressing the revelations, they’d impugn the credibility and motives of “the leaker.” Given the stakes, I had to seize the initiative before it was too late. If I didn’t explain my actions and intentions, the government would, in a way that would swing the focus away from its misdeeds.

Page 294

All of these people, whether they faced prison or not, encountered some sort of backlash, most often severe and derived from the very abuse that I’d just helped expose: surveillance. If ever they’d expressed anger in a private communication, they were “disgruntled.” If they’d ever visited a psychiatrist or a psychologist, or just checked out books on related subjects from a library, they were “mentally unsound.” If they’d been drunk even once, they were said to be alcoholics. If they’d had even one extramarital affair, they were said to be sexual deviants. Not a few lost their homes and were bankrupted. It’s easier for an institution to tarnish a reputation than to substantively engage with principled dissent—for the IC, it’s just a matter of consulting the files, amplifying the available evidence, and, where no evidence exists, simply fabricating it.

Page 296

I wouldn’t usually name them, but since they have bravely identified themselves to the press, I will: Vanessa Mae Bondalian Rodel from the Philippines, and Ajith Pushpakumara, Supun Thilina Kellapatha, and Nadeeka Dilrukshi Nonis, all from Sri Lanka. These unfailingly kind and generous people came through with charitable grace. The solidarity they showed me was not political. It was human, and I will be forever in their debt. They didn’t care who I was, or what dangers they might face by helping me, only that there was a person in need. They knew all too well what it meant to be forced into a mad escape from mortal threat, having survived ordeals far in excess of anything I’d dealt with and hopefully ever will: torture by the military, rape, and sexual abuse. They let an exhausted stranger into their homes—and when they saw my face on TV, they didn’t falter. Instead, they smiled, and took the opportunity to reassure me of their hospitality. Though their resources were limited—Supun, Nadeeka, Vanessa, and two little girls lived in a crumbling, cramped apartment smaller than my room at the Mira—they shared everything they had with me, and they shared it unstintingly, refusing my offers to reimburse them for the cost of taking me in so vociferously that I had to hide money in the room to get them to accept it. They fed me, they let me bathe, they let me sleep, and they protected me. I will never be able to explain what it meant to be given so much by those with so little, to be accepted by them without judgment as I perched in corners like a stray street cat, skimming the Wi-Fi of distant hotels with a special antenna that delighted the children. Their welcome and friendship was a gift, for the world to even have such people is a gift, and so it pains me that, all these years later, the cases of Ajith, Supun, Nadeeka, and Nadeeka’s daughter are still pending. The admiration I feel for these folks is matched only by the resentment I feel toward the bureaucrats in Hong Kong, who continue to deny them the basic dignity of asylum. If folks as fundamentally decent and selfless as these aren’t deemed worthy of the protection of the state, it’s because the state itself is unworthy. What gives me hope, however, is that just as this book was going to press, Vanessa and her daughter received asylum in Canada. I look forward to the day when I can visit all of my old Hong Kong friends in their new homes, wherever those may be, and we can make happier memories together in freedom.

Note: The state itself is unworthy

Page 300

With my government having decided to charge me under the Espionage Act, I stood accused of a political crime, meaning a crime whose victim is the state itself rather than a person. Under international humanitarian law, those accused in this way are generally exempt from extradition, because the charge of political criminality is more often than not an authoritarian attempt at quashing legitimate dissent. In theory, this means that government whistleblowers should be protected against extradition almost everywhere. In practice, of course, this is rarely the case, especially when the government that perceives itself wronged is America’s—which claims to foster democracy abroad yet secretly maintains fleets of privately contracted aircraft dedicated to that form of unlawful extradition known as rendition, or, as everyone else calls it, kidnapping.

Note: I love his writing

Page 302

Despite my caution, I was in a difficult position, and as Hemingway once wrote, the way to make people trustworthy is to trust them.

Note: He’s well read

Page 309

All told, we were trapped in the airport for a biblical forty days and forty nights. Over the course of those days, I applied to a total of twenty-seven countries for political asylum. Not a single one of them was willing to stand up to American pressure, with some countries refusing outright, and others declaring that they were unable to even consider my request until I arrived in their territory—a feat that was impossible. Ultimately, the only head of state that proved sympathetic to my cause was Burger King, who never denied me a Whopper (hold the tomato and onion).

Note: Hahaha. Even when things seem bleak he’s hilarious

Page 322

Been packing the house for days now with only minor interruptions from the FBI, coming by with more forms to sign. It’s torture, going through everything. Finding all these little things that remind me of him. I’m like a crazy woman, cleaning up, and then just gazing at his side of the bed. More often, though, I find what’s missing. What the FBI took. Technology, yes, but also books. What they left behind were footprints, scuff marks on the walls, and dust.

Note: Reminds me of the search scene in Lives of Others

Page 324

burned and the smoke rose into the sky. The glow and the smoke reminded me of the trip I took with Wendy to Kilauea, the volcano on the Big Island. That was just over a month ago, but it feels like years in the past. How could we have known that our own lives were about to erupt? That Volcano Ed was going to destroy everything? But I remember the guide at Kilauea saying that volcanoes are only destructive in the short term. In the long term, they move the world. They create islands, cool the planet, and enrich the soil. Their lava flows uncontrolled and then cools and hardens. The ash they shoot into the air sprinkles down as minerals, which fertilize the earth and make new life grow.

Note: Holy shit who writes this well in a diary

Page 326

In America, the initial press reports on the disclosures started a “national conversation,” as President Obama himself conceded. While I appreciated the sentiment, I remember wishing that he had noted that what made it “national,” what made it a “conversation,” was that for the first time the American public was informed enough to have a voice.

Page 327

ACLU v. Clapper was a notable victory, to be sure. A crucial precedent was set. The court declared that the American public had standing: American citizens had the right to stand in a court of law and challenge the government’s officially secret system of mass surveillance.

Page 332

Who among us can predict the future? Who would dare to? The answer to the first question is no one, really, and the answer to the second is everyone, especially every government and business on the planet. This is what that data of ours is used for. Algorithms analyze it for patterns of established behavior in order to extrapolate behaviors to come, a type of digital prophecy that’s only slightly more accurate than analog methods like palm reading. Once you go digging into the actual technical mechanisms by which predictability is calculated, you come to understand that its science is, in fact, anti-scientific, and fatally misnamed: predictability is actually manipulation. A website that tells you that because you liked this book you might also like books by James Clapper or Michael Hayden isn’t offering an educated guess as much as a mechanism of subtle coercion.

Note: Not sure I agree with this

Page 332

We can’t allow ourselves to be used in this way, to be used against the future. We can’t permit our data to be used to sell us the very things that must not be sold, such as journalism. If we do, the journalism we get will be merely the journalism we want, or the journalism that the powerful want us to have, not the honest collective conversation that’s