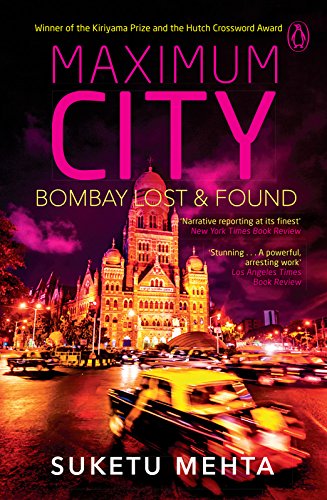

Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found

by Suketu Mehta

- Author:

- Suketu Mehta

- Status:

- Done

- Format:

- eBook

- Reading Time:

- 13:07

- Genres:

- India , Nonfiction , Travel , History , Indian Literature , Asia , Cities

- Pages:

- 600

- Highlights:

- 65

Highlights

Page 19

India is the Country of the No. That ‘no’ is your test. You have to get past it. It is India’s Great Wall; it keeps out foreign invaders. Pursuing it energetically and vanquishing it is your challenge. In the guru–shishya tradition, the novice is always rebuffed multiple times when he first approaches the guru. Then the guru stops saying no but doesn’t say yes either; he suffers the presence of the student. When he starts acknowledging him, he assigns a series of menial tasks, meant to drive him away. Only if the disciple sticks it out through all these stages of rejection and ill treatment is he considered worthy of the sublime knowledge. India is not a tourist-friendly country. It will reveal itself to you only if you stay on, against all odds. The ‘no’ might never become a ‘yes’. But you will stop asking questions. ‘Can I rent a flat at a price I can afford?’ ‘No.’

Page 20

The landlord is a Palanpuri Jain and a strict vegetarian. He asks my uncle if we are too. ‘Arre, his wife is a Brahmin! Even more than us!’ my uncle replies. And this is where we get our vegetarian discount: twenty per cent off the asking rent. But in my uncle’s words is evident the subtle contempt with which the Vaisyas—the merchant castes—regard the Brahmins.

Page 25

Meanwhile, I am paying rent every month to my landlord for the privilege of fixing his flat.

Page 26

a dozen private and public companies offering mobile phone services, while the basic land telephone network is in terrible shape;

Note: Get fucked m8

Page 27

My friend Manjeet tells me to take her mother to another gas office. She knows the ways of Bombay. We walk in, and I tell the clerk, ‘I need a gas cylinder, please.’ I explain the problem with the other office, their lack of quota. ‘Do you know a member in the Rajya Sabha?’ the clerk asks. ‘No. Why should I?’ ‘Because if you did, it would be easy. All the Rajya Sabha MPs have a discretionary quota of gas cylinders they can award.’ At this point Manjeet’s mother steps in. ‘He has two children!’ she appeals to the female bureaucrats. ‘Two small children! They don’t even have gas to boil milk! They are crying for milk! What is he supposed to do without gas to boil milk for his two small children?’ By the next morning we have a gas cylinder in our kitchen. My friend’s mother knew what had to be done to move the bureaucracy. She did not bother with official rules and procedures and forms. She appealed to the hearts of the workers in the office; they have children too. And then they volunteered the information that there was a loophole: If I ordered a commercial tank of gas, which is bigger and more expensive than the household one, I could get one immediately. No one had told me this before. But once the emotional connection was made, the rest was easy. Once the workers in the gas office were willing to pretend that my household was a business, they delivered the cylinders every couple of months efficiently, spurred on by the vision of my two little children crying for milk.

Page 32

Sau me ek sau ek beimaan. Phir bhi mera Bharat mahaan.

Page 38

The third page of the Bombay Times and the back pages of the Indian Express and the columns of the Sunday edition of Mid-Day and the metro sections of the newsmagazines are the envy pages, all designed to make the reader feel poorer, uglier, smaller and, most of all, socially outcast.

Page 41

I have another purpose for this stay: to update my India. So that my work should not be just an endless evocation of childhood, of loss, of a remembered India, I want to deal with the India of the present.

Page 42

The two other Shiv Sena men with Sunil looked at each other. Either they didn’t trust me yet or they were not drunk enough on my cognac. ‘I wasn’t there. The Sena didn’t have anything to do with the rioting,’ one man said.

Note: Lmaaaaao

Page 42

‘Those were not days for thought,’ he continued. ‘We five people burned one Mussulman. At 4 a.m., after we heard of Radhabai Chawl, a mob assembled, the likes of which I have never seen. Ladies, gents. They picked up any weapon they could. Then we marched to the Muslim side. We met a pav-wallah on the highway, on a bicycle. I knew him; he used to sell me bread every day.’ Sunil held up a piece of bread from the pav bhaji he was eating. ‘I set him on fire. We poured petrol on him and set him on fire. All I thought was, This is a Muslim. He was shaking. He was crying, “I have children, I have children!” I said, “When your Muslims were killing the Radhabai Chawl people, did you think of your children?” That day we showed them what Hindu dharma is.’

Note: Jesus

Page 43

Bal Thackeray. It was he who had formed, in 1966, a nativist political party called the Shiv Sena—Shivaji’s Army—

Note: Lol all this time I thought the God Shiva

Page 45

they always produced ten or twelve children when Hindus stopped at two or three. In Bombay, numbers of people are important, the sense of being crowded by the Other in an already overcrowded city is very strong. ‘In a few years they will be more than us,’ the municipal employee predicted gloomily.

Page 46

Sunil saw no irony in the fact that when his daughter was sick he went to the same Muslim community that he massacred and burned during the riots.

Page 59

I asked one of the Jogeshwari women if she wouldn’t rather live in a decent apartment than the slum she lived in now, with the open gutter outside and the absence of indoor plumbing. Yes, there was a building planned nearby to resettle the slum dwellers. But people from her neighbourhood wouldn’t move there. ‘There’s too much aloneness. A person can die behind the closed doors of a flat and no one will know. Here,’ she observed with satisfaction, ‘there are a lot of people.’ Be it ever so humble, there’s no place like home. We tend to think of a slum as an excrescence, a community of people living in perpetual misery. What we forget is that out of inhospitable surroundings, they form a community, and they are as attached to its spatial geography, the social networks they have built for themselves, the village they have recreated in the midst of the city, as a Parisian might be to his quartier or as I was to Nepean Sea Road. ‘I like this place,’ said Arifa Khan of her home and her basti. ‘This is mine. I know the people here and I like the facilities here.’ Any urban redevelopment plan has to take into account the curious desire of slum dwellers to live closely together. A greater horror than open gutters and filthy toilets, to the people of Jogeshwari, is an empty room in the big city.

Page 67

As for the courts, Thackeray is unfazed by their power. In June 1993, the Saheb declared, ‘I piss on the court’s judgements. Most judges are like plague-ridden rats. There must be direct action against them.

Page 70

The new leaders are extravagantly corrupt, unlike the older Oxbridge-educated ones, whose noblesse oblige and feudal wealth kept them from wholesale plunder of the public purse.

Page 77

It is an exact and precise hell, the life of an unemployed young man in India. For eighteen years you have been brought up as a son; you have been given the best of what your family can afford. In the household, you eat first, then your father, then your mother, then your sister. If there is only so much money in the household, your father will do with half his cigarettes, your mother won’t buy her new sari, and your sister will stay home, but you will be sent to school. So when you reach the age of eighteen, you have your worshipful family’s expectations behind you. You dare not turn around. You know what is expected of you; you have been witness to all the petty humiliations they have suffered to get you to this place. You now need to deliver. Your sister is getting married, your mother is sick, and your father will retire next year. It’s up to you; you carry a heavy burden of guilt from your childhood for having heedlessly taken the best of everything. So when you go out with your matriculation certificate or your BA and find there are no jobs—the big companies have stopped hiring or are leaving the city altogether, and the small companies will hire only relatives of people already working there, and your family is from Raigad or Bihar and has no influence here—you will look for other ways of making money. You will look for other ways of assuring your family that their investment wasn’t lost. You can take beatings, you can take rejection, but you can’t face your family if you don’t do your duty as the son. Go out in the morning and come back at night, or go out at night and come back in the daytime if you have to, but take care of the family. You owe it to them; it is your dharma.

Page 82

In the post-Marxist age, we can no longer believe that redistribution solves anything, that making the rich poorer will make the poor richer. It is the death not just of ideology but of ideas. Nothing in the national debate has any strong conviction. On the right, a vague belief in foreign investment; on the left, a vague and poorly articulated fear of it. The left is apologetic about being left.

Page 82

After fifty years of experiments in socialism, who can argue with a straight face that central planning is the answer to poverty? One slogan that has been conspicuously absent from the electioneering has been ‘Garibi Hatao’. It’s as if there is a tacit acknowledgement on all sides that the poverty is insurmountable, so we’ll move on and tackle something else— corruption or multinationals or whether we should have a temple or mosque in Ayodhya.

Page 87

The Sena government officially rejects the report, accusing the judge of being biased against the Hindus. But this most learned judge is a Sanskrit scholar; nobody is fooled. Justice Srikrishna is a devout Hindu, much more so than Bal Thackeray.

Page 94

‘How can a man kill?’ I ask Amol. ‘How can he bring himself to do it?’ ‘You are a writer. After drinking you will say to yourself, Now I must write a story. If you are a dancer, after drinking you will feel like dancing. If you are a killer, after drinking you will think, Now I must kill somebody.’ Amol flexes his arms. ‘It’s what you do; it’s in your nature.’

Page 103

Meanwhile, from Malabar Hill, a friend in the fashion industry calls me on my mobile with a question. He has decided to vote for the first time in his life today. ‘I’m in your old neighbourhood,’ he says. He is entering Walshingham House School, where the voting station is located. ‘There are two boxes in front of me. One says Lok Sabha, one says Vidhan Sabha. Which is the centre and which is the state?’ he asks me.

Page 108

Who has the right to live in Bombay? The Shiv Sena is primarily a party of exclusion. It sought from the beginning to say, this or that group does not belong here. It was the Gujaratis first, then the south Indians, then the communists, then the Dalits, and now the Muslims. Bombay is, like any other Indian city, full of people in search of answers to the question ‘Who am I?’ and believing that the answer, when they find it, will allow them also to answer the other question: ‘Who is not I?’ People like Thackeray approach the question backwards. If they answer the question ‘Who is not I?’ they will, by a process of elimination, find the answer to ‘Who am I?’

Page 112

‘hang him’. It is a phrase the Saheb often uses, an all-purpose solution for Bangladeshi Muslims and Sanjay Dutt alike. This leader doesn’t waste time on theory or process, he advocates direct immediate action: Hang them. A leader whom a young man, with little education but a lot of anger, can understand, can worship.

Page 118

Sanjay Nirupam, a Shiv Sena MP, sees opportunity if his leader is arrested. ‘After the 1993 riots we won thirty out of thirty-four seats in the elections,’ he points out to me. ‘If this is a democracy, the people have spoken. Another riot is to our political advantage.’

Page 120

The ethos—that much-abused word— of India is against such homogeneity. But a fair-minded person can look around Bombay and see that it really is too crowded. Somebody needs to go. But who? Well, you start with the poorest. Or the newest. Or the one farthest away from yourself, however you define yourself. Immigrants hope, ultimately, to be in a position where they have the right to keep out new immigrants, to tell the next person to get off the train in your city, that he must go back, he can’t stay. That’s when you know you’re truly native.

Page 120

Chotta Shakeel, the operational commander of the Muslim gangs, is doing what the government has failed to do. He is extracting revenge for the riots. He is going after people like the ex-mayor Milind Vaidya, who was named in the Srikrishna Report for having personally attacked Muslims. Shakeel is consulting the report; he is the executive to Srikrishna’s judiciary.

Page 126

There are also 400,000 empty residences in the city, empty because the owners are afraid of losing them to tenants if they rent them out. Assuming each apartment can house a family of five people, on average, that’s two million people—one-fourth of the homeless—who could immediately find shelter if the laws were to be amended.

Page 127

Another cancerous outgrowth of the Bombay Rent Act is the ‘paying guest’. In looking for an office, I am referred to the ‘PG rooms’, which are rooms in someone else’s flat. The city has a whole tribe of ‘paying guests’, usually young professionals from other cities, suffering the daily humiliations imposed on them by their landlords—what time you can come in and who you can bring with you, how much ice you’re entitled to from the fridge, how loud you can play your music. There are three personal gods that every Hindu is supposed to revere: mother, father, guest. There is no category for ‘paying guest’.

Page 128

The Indian government has long believed in the unreality of supply and demand; what you pay for an item, for a food or for a service, has no relation to what it costs the producer.

Page 129

What we could do so exquisitely in this country a thousand years ago we can’t even attempt today. We were making some of the greatest art of the ancient world. Shattered by invasion and colonialism and an uneasy accommodation with modernity, we now can’t construct five pillars of equal proportions. We built the Konarak Temple, Hampi, the Taj Mahal. Then what happened?

Note: Ok stop there

Page 136

the most potent issue in Bombay’s politics and the saddest: How do you provide a measure of justice to those who built the city, once the city has no further use for them?

Page 138

The bank’s solution was to propose building 100,000 public toilets. It was an absurd idea. I have seen public latrines in the slums. None of them work. People defecate all around the toilets, because the pits have been clogged for months or years. To build 100,000 public toilets is to multiply this problem a hundredfold. Indians do not have the same kind of civic sense as, say, Scandinavians. The boundary of the space you keep clean is marked at the end of the space you call your own. The flats in my building are spotlessly clean inside; they are swept and mopped every day, or twice every day. The public spaces—hallways, stairs, lobby, the building compound— are stained with betel spit; the ground is littered with congealed wet garbage, plastic bags, and dirt of human and animal origin. It is the same all over Bombay, in rich and poor areas alike.

Page 149

The city recovered quickly after the blasts. The Stock Exchange, which had been bombed, reopened two days later, using the old manual trading because the computers were destroyed, and its index actually gained 10 per cent in the next two days. Just to show them.

Page 154

The money goes abroad through the hawala networks, a paperless money-laundering system in which a bag of rupees given to a shopkeeper or diamond merchant in Bombay transforms itself quickly and efficiently into an envelope full of dollars in Dubai.

Page 190

Seventy-three per cent of the country’s jail population is on trial or waiting for a trial; only a quarter of them are actually serving out a sentence. Each year, forty thousand new cases are filed in Bombay.

Page 191

The judge–population ratio in the US is 107 judges per million people; in India it is thirteen per million. Forty per cent of the judgeships in the Bombay High Court are vacant; each judge has over three thousand cases pending. Qualified lawyers do not want to be behind the bench, because the pay is too low compared with what they can earn in private practice. There are no costs associated with filing lawsuits, so the overwhelming majority are frivolous.

Page 193

‘It is a good city for gangwar,’ observes Mama. Like an area of lower pressure in the atmosphere, the underworld enters the areas that the state has withdrawn from—the judiciary, personal protection, the channelling of capital. The men in the gangwar see themselves as hardworking men. As Chotta Shakeel explained to a journalist friend of mine, ‘There are blue-collar workers and white-collar workers. We are black-collar workers.’

Page 253

I go with Sunita into the city to meet an old friend, to take in a movie, to have dinner. But the rest of the world seems trivial. Their conversations revolve around trivialities: careers, taxes, shopping. Nobody in that Bombay talks about god, or sin and virtue, or death except when it is imminent, looming over a near relative, and then it is dealt with in a quick, frightened fashion, as if to get it out of the way as quickly as possible. But I have been immersed in extended contemplation of those questions with people who have to face them every hour of every day, and it has been exhilarating. The last time I can recall exploring those topics in such depth was with my grandfather, as he lay dying in my uncle’s house in Bombay. But I was not as close to death then as I was in that hotel room. Now, ordinary conversations bore me. ‘How much more do you need?’ my wife, my friends keep asking me, concerned about my safety. They are asking the question based on the wrong premise. They think I keep meeting the gangsters for material for my book.

Page 257

As Police Commissioner M.N. Singh said, summarizing the conversation, ‘A judge has lost faith in the judiciary and approaches a gangster to settle a personal matter.’

Page 315

Why does she do it? Why does she cut and burn herself? ‘I was angry.’ ‘Who at?’ Herself, she answers. When she gets angry at a man, ‘when he doesn’t understand what I want, when he doesn’t understand what I need, I get angry at myself. Why is the person opposite behaving like this with me when I don’t take any money from him?’ It is a term she often uses to describe her men: ‘the person opposite’. Since the person opposite is treating her badly, and she can find no reason for his bad behaviour, the fault must lie with her. It must be her fault that he’s so selfish, so unthinking.

Page 351

When Honey got famous and successful, this same uncle came to her to ask her for a loan of three lakh, for another shop, and Honey give him the money.

Note: Typo

Page 357

And then I understand why older men fall in love with younger women. It is not because of their bodies; that is enough for lust but not for love. It is because of their minds—new, clean, still not cynical, still not hard. They drink their newness.

Page 379

Who is a South Asian? Someone who watches Hindi movies. Someone whose being fills up with pleasure when he or she hears ‘Mere sapno ki rani’ or ‘Kuch kuch hota hai’. Here is our national language; here is our common song.

Note: Wrong

Page 382

I point out to Vinod that the Indian audience is fully capable of understanding complexity; after all, it is schooled in the most complex narrative myths in the world, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Each character in the epics is multidimensional, the plots are multilayered, and the message is morally ambiguous, demanding a high degree of thought. There is nothing easy about the epics and they both end unhappily,

Note: Fuck outta here

Page 384

Vinod himself is devoted, like a good Hindi movie son, to his mother. He cancels dinner plans with us once because his mother says you can’t eat food cooked during an eclipse.

Note: Chutiya

Page 385

This is something I gradually find out about Bollywood: The people working in it are far smarter than the product they turn out. ‘We are dwarfing our intellectual selves in order to make films for a Hindi film audience. You’re writing this great novel in the English language. Try doing it in Hindi; then you’ll know my tragedy. You’ll get fucked. You’ll have no fucking money to pay your children’s school fees.’

Page 396

Bollywood is essentially a Punjabi- and Sindhi-dominated industry, founded by Partition refugees who took up a business that the established Bombay elites of the 1940s looked down on. In this, it parallels the story of Hollywood and the Jews. The saga of Partition fits with the great love stories of this part of the world, of Laila–Majnu, Heer–Ranjha and thousands of Hindi movies: two people who love each other against all odds against the tyrant father or the state; or twin brothers separated at birth in an accident of history. Partition, with all its heightened emotion, its sweep and tragedy, is a ready-made plot for Bollywood. It fits within the formula. Perhaps, deep in the scarred psyches of the refugees who made Bollywood what it is today, Partition created the formula.

Page 415

After the political cuts are made, Zakhm is released and goes on to win an award from the President of India: Best Feature Film on National Integration.

Note: This entire process of clearing it with the censors is fucking stupid. But I wonder, what would India be without it?

Page 434

The plot, like the Lord, moves in mysterious ways. The storytelling style of the movie follows a kind of jump cutting of the script. A character proceeds from one momentous event in his life to another—marriage, expulsion from the family, heartbreak—without the tedious intermediary details of motivation or purpose explained to the audience. You see them going from point A to point Z; the intervening alphabet actions have occurred off screen. As a result, each succeeding scene is a happy surprise, because you never know what to expect next. My attention is seized in a way that it never is in mainstream Hindi films.

Page 444

Bal Thackeray, leader of the political party that was responsible for the riots which made him so fearful he had to ask for guns to protect his family from them. Because Bal Thackeray is the same man who, having demonstrated to all Bombay that he could put the Muslims in their place, also demonstrated his power, his magnanimity and his love of the film industry by ordering his government to furnish bail for Sanjay Dutt, son of the Muslim Nargis Dutt.

Page 448

In the middle of shooting a scene, the crew hears a series of loud pops. ‘They’re fireworks; they’re celebrating Dussehra,’ Vinod explains to the crew, and asks the cameraman to hurry up with the shot. After it’s finished, he shouts out to his unit to pack up fast and clear the area. The crew now realizes there is no Dussehra in Muslim Kashmir; that was real shooting going on around them. Rocket-propelled grenades had been fired at the government secretariat, 200 yards away from the set, and four people had died. But the shot got taken.

Page 476

On the other hand, a teacher fond of me pointed out, ‘Gandhiji also had bad handwriting.’ I took considerable solace in that observation and eagerly sought out all samples of the Mahatma’s scrawl, until I was convinced that bad handwriting was not only compensated for by greatness later on in life but a prerequisite for it.

Page 482

I first learned my Hinduism through my grandmother, and it was unanalytical, mystical. Then I learned it again, in American universities. The stories that those people in the temple know by heart we needed to have explained to us by American academics.

Note: Cliche

Page 508

So that some day, like the Thakkars, your eldest son can buy two rooms on Mira Road. And the younger one can move beyond that, to New Jersey. Your discomfort is an investment. Like insect colonies, people here will sacrifice their individual pleasures for the greater progress of the family. One brother will work and support all the others, and he will gain a deep satisfaction from the fact that his younger brother is taking an interest in computers and will probably go on to America. His brother’s progress will make him think that his life has meaning, that it is being well spent working in the perfume company, trudging in the heat every day to peddle Drakkar Noir knockoffs to shop owners who don’t really want it. In families like the Thakkars, there is no individual, only the organism. Everything—Girish’s desire to go abroad and make and send back money, Dharmendra’s taking a wife, Raju’s staying at home—is for the greater good of the whole. There are circles of fealty and duty within the organism, but the smallest circle is the family. There is no circle around the self.

Page 530

Car ads in most countries usually focus on the luxurious cocoon that awaits you, the driver, once you step inside. At most, there might be space for the attractive woman you’ll pick up once you’re spotted driving the flashy set of wheels. The Ambassador ad isn’t really touting the virtues of space. It’s not saying, like a station wagon ad, that it has lots of spare room. It’s saying that the kind of people likely to drive an Ambassador will always make more room. It is really advocating a reduction of personal physical space and an expansion of the collective space. In a crowded city, the citizens of Bombay have no option but to adjust.

Page 531

So when the station arrives, you must be in position to spring off, well before the train has come to a complete stop, because if you wait until it has stopped, you will be swept back inside by the people rushing in. In the mornings, by the time the train gets to Borivali, the first stop, it is always chockful. ‘To get a seat?’ I ask. Girish looks at me, wondering if I’m stupid. ‘No. To get in.’

Page 534

If you are late for work in the morning in Bombay, and you reach the station just as the train is leaving the platform, you can run up to the packed compartments and find many hands stretching out to grab you on board, unfolding outwards from the train like petals. As you run alongside the train, you will be picked up and some tiny space will be made for your feet on the edge of the open doorway. The rest is up to you. You will probably have to hang on to the door frame with your fingertips, being careful not to lean out too far lest you get decapitated by a pole placed too close to the tracks. But consider what has happened. Your fellow passengers, already packed tighter than cattle are legally allowed to be, their shirts already drenched in sweat in the badly ventilated compartment, having stood like this for hours, retain an empathy for you, know that your boss might yell at you or cut your pay if you miss this train, and will make space where none exists to take one more person with them. And at the moment of contact, they do not know if the hand that is reaching for theirs belongs to a Hindu or Muslim or Christian or Brahmin or untouchable or whether you were born in this city or arrived only this morning or whether you’re from Malabar Hill or New York or Jogeshwari. All they know is that you’re trying to get to the city of gold, and that’s enough. Come on board, they say. We’ll adjust.

Page 536

My family never thought of the Jains as members of a separate religion, we just regarded them as especially, sometimes nuttily, orthodox Hindus.

Page 538

He had already ceased using allopathic medicine eighteen years ago, well before his interest in his religion had been awakened. After the twins were born, they were in some pain. Sevantibhai went to an ayurvedic doctor in Khetwadi, who gave him the urine of a cow. He made the babies drink it twenty-one times a day, and they got better.

Note: Fml

Page 538

‘You have to import the petrol from Saudi Arabia and send them things like laboratory mice and human blood in exchange.’

Page 549

But now, Sevantibhai Chimanlal Ladhani, the dark little man with the easy smile, is not just a moderately successful diamond merchant. He has become a figure of power, a leader on the path that even the billionaire Arunbhai will have to tread sooner or later. In one bound, he has surpassed people far more successful in business than he. He is now, in this hall, on this afternoon, the subject of their admiration, even of their envy.

Note: Feels like this dude did this for the admiration

Page 566

They want to play, they’re still young. Not cricket, of course—the ball hitting the bat is himsa—

Note: Facepalm

Page 572

‘Where I sit a lady can’t sit for 144 minutes, and where a lady sits I can’t sit for forty-eight minutes, because the aura of the body lingers on.’

Page 578

When I first came here I thought I was here in the city’s final stages. Then I moved to a nicer apartment. A city is only as thriving or sickly as your place in it. Each Bombayite inhabits his own Bombay.

Note: Word