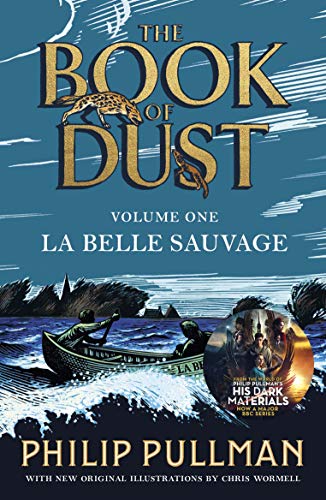

La Belle Sauvage

by Philip Pullman

- Author:

- Philip Pullman

- Status:

- Done

- Format:

- eBook

- Reading Time:

- 8:24

- Genres:

- Fantasy , Fiction , Young Adult , Adventure , Childrens , Science Fiction Fantasy

- Pages:

- 592

- Highlights:

- 6

Highlights

Page 68

He was known to many of the scholars and other visitors, and generously tipped, but becoming rich was never an aim of his; he took tips to be the generosity of providence, and came to think of himself as lucky, which did him no harm in later life. If he’d been the sort of boy who acquired a nickname he would no doubt have been known as ‘Professor’, but he wasn’t that sort of boy. He was liked when noticed, but not noticed much, and that did him no harm either.

Page 121

He supposed that when he was grown up he’d help his father in the bar, and then take over the place when his parents grew too old to continue. He was fairly happy about that. It would be much better running the Trout than many other inns, because the great world came through, and scholars and people of consequence were often there to talk to. But what he’d really have liked to do was nothing like that. He’d have liked to be a scholar himself, maybe an astronomer or an experimental theologian, making great discoveries about the deepest nature of things. To be a philosopher’s apprentice, now – that would be a fine thing. But there was little likelihood of that; Ulvercote Elementary School prepared its pupils for craftsmanship or clerking at best, before passing them out into the world at fourteen, and as far as Malcolm knew there were no openings in scholarship for a bright boy with a canoe.

Note: class system

Page 207

Malcolm got up eagerly and scanned the shelves. Hannah watched, sitting back, not wanting to force anything on him. When she was a young girl, an elderly lady in the village where she grew up had done the same for her, and she remembered the delight of choosing for herself, of being allowed to range anywhere on the shelves. There were two or three commercial subscription libraries in Oxford, but no free public library, and Malcolm wouldn’t be the only young person whose hunger for books had to go unsatisfied. So she felt good at seeing him so keen and happy as he ranged along, picking out books and looking at them and reading the first page and putting them back before trying another. She saw herself in this curious boy. At the same time she felt horribly guilty. She was exploiting him; she was putting him in danger. She was making a spy out of him. That he was brave and intelligent made it no better; he was still so young that he was unconscious of the chocolatl remaining on his top lip. It wasn’t something he could volunteer for, though she guessed he would have done so eagerly; she had pressured him, or tempted him. She had more power, and she had done that.

Page 505

Dibdin was a thin, sandy-coloured man,

Page 486

‘But who is he? What’s he do?’ ‘Goodness knows. If you don’t like the look of him, stay away from him.’ That was the trouble with his mother: she thought an instruction was an explanation. Well, he’d ask his father later.

Page 220

‘One more thing,’ Nugent went on. ‘Your young friend, the boy from the inn – Matthew, is it?’ ‘Malcolm Polstead.’ ‘Malcolm. We won’t put him in danger, but he could be valuable in a number of ways. Keep in touch with him. Tell him anything you think he can keep quiet about. Pick up whatever you can.’ Something had happened. The atmosphere in the room had changed, quite suddenly. There was an air of … she couldn’t understand it – it was as if the others all knew a secret she didn’t, and they didn’t want to look at her. It couldn’t have been Lord Nugent’s words, which seemed innocuous enough; or was she missing what they meant? The moment passed. People got up, goodbyes were said, coats found, thanks uttered; and Hannah put the alethiometer in its rosewood box in a cotton shopping bag, and set off home. ‘Jesper, what happened then?’ she said when they’d turned into the Woodstock Road. ‘They knew that he meant something underneath what he actually said, and they didn’t like it.’ ‘Well, I got that far myself. I wonder what it was.’