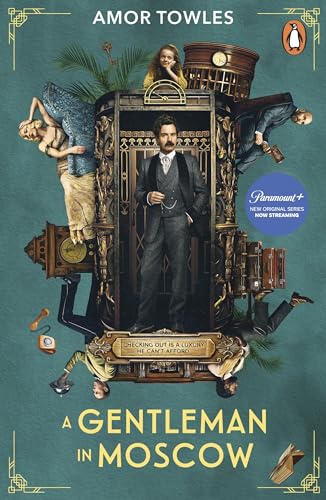

A Gentleman in Moscow

by Amor Towles

- Author:

- Amor Towles

- Status:

- Done

- Format:

- eBook

- Genres:

- Historical Fiction , Fiction , Book Club , Historical , Russia , Literary Fiction

- Pages:

- 462

- Highlights:

- 54

Highlights

Page 194

egret

Page 215

’Tis a funny thing, reflected the Count as he stood ready to abandon his suite. From the earliest age, we must learn to say good-bye to friends and family. We see our parents and siblings off at the station; we visit cousins, attend schools, join the regiment; we marry, or travel abroad. It is part of the human experience that we are constantly gripping a good fellow by the shoulders and wishing him well, taking comfort from the notion that we will hear word of him soon enough. But experience is less likely to teach us how to bid our dearest possessions adieu. And if it were to? We wouldn’t welcome the education. For eventually, we come to hold our dearest possessions more closely than we hold our friends. We carry them from place to place, often at considerable expense and inconvenience; we dust and polish their surfaces and reprimand children for playing too roughly in their vicinity—all the while, allowing memories to invest them with greater and greater importance. This armoire, we are prone to recall, is the very one in which we hid as a boy; and it was these silver candelabra that lined our table on Christmas Eve; and it was with this handkerchief that she once dried her tears, et cetera, et cetera. Until we imagine that these carefully preserved possessions might give us genuine solace in the face of a lost companion. But, of course, a thing is just a thing. And so, slipping his sister’s scissors into his pocket, the Count looked once more at what heirlooms remained and then expunged them from his heartache forever.

Page 241

dormer.

Page 302

mille-feuille

Page 486

Admittedly, the Count had felt a touch of concern when he’d first lifted the book from the desk the day before. For as a single volume, it had the density of a dictionary or Bible—those books that one expects to consult, or possibly peruse, but never read. But it was the Count’s review of the Contents—a list of 107 essays on the likes of Constancy, Moderation, Solitude, and Sleep—that confirmed his initial suspicion that the book had been written with winter nights in mind. Without a doubt, it was a book for when the birds had flown south, the wood was stacked by the fireplace, and the fields were white with snow; that is, for when one had no desire to venture out and one’s friends had no desire to venture in.

Note: Yeah I’ve read books like this.

Page 535

Next was the shop of Fatima Federova, the florist. A natural casualty of the times, Fatima’s shelves had been emptied and her windows papered over back in 1920, turning one of the hotel’s brightest spots into one of its most forlorn. But in its day, the shop had sold flowers by the acre. It had provided the towering arrangements for the lobby, the lilies for the rooms, the bouquets of roses that were tossed at the feet of the Bolshoi ballerinas, as well as the boutonnieres on the men who did the tossing. What’s more, Fatima was fluent in the floral codes that had governed polite society since the Age of Chivalry. Not only did she know the flower that should be sent as an apology, she knew which flower to send when one has been late; when one has spoken out of turn; and when, having taking notice of the young lady at the door, one has carelessly overtrumped one’s partner. In short, Fatima knew a flower’s fragrance, color, and purpose better than a bee. Well, Fatima’s may have been shuttered, reflected the Count, but weren’t the flower shops of Paris shuttered under the “reign” of Robes-pierre, and didn’t that city now abound in blossoms? Just so, the time for flowers in the Metropol would surely come again.

Note: I wonder if that time ever came again.

Page 750

“Why is it that our nation above all others embraced the duel so wholeheartedly?” he asked the stairwell rhetorically. Some, no doubt, would simply dismiss it as a by-product of barbarism. Given Russia’s long, heartless winters, its familiarity with famine, its rough sense of justice, and so on, and so on, it was perfectly natural for its gentry to adopt an act of definitive violence as the means of resolving disputes. But in the Count’s considered opinion, the reason that dueling prevailed among Russian gentlemen stemmed from nothing more than their passion for the glorious and grandiose. True, duels were fought by convention at dawn in isolated locations to ensure the privacy of the gentlemen involved. But were they fought behind ash heaps or in scrapyards? Of course not! They were fought in a clearing among the birch trees with a dusting of snow. Or on the banks of a winding rivulet. Or at the edge of a family estate where the breezes shake the blossoms from the trees… . That is, they were fought in settings that one might have expected to see in the second act of an opera. In Russia, whatever the endeavor, if the setting is glorious and the tenor grandiose, it will have its adherents. In fact, over the years, as the locations for duels became more picturesque and the pistols more finely manufactured, the best-bred men proved willing to defend their honor over lesser and lesser offenses. So while dueling may have begun as a response to high crimes—to treachery, treason, and adultery—by 1900 it had tiptoed down the stairs of reason, until they were being fought over the tilt of a hat, the duration of a glance, or the placement of a comma.

Page 802

“A princess would be raised to show respect for her elders.” Nina bowed her head toward the Count in deference. He coughed. “I wasn’t referring to me, Nina. After all, I am practically a youth like yourself. No, by ‘elders,’ I meant the gray haired.” Nina nodded to express her understanding. “You mean the grand dukes and grand duchesses.” “Well, yes. Certainly them. But I mean elders of every social class. The shopkeepers and milkmaids, blacksmiths and peasants.” Never hesitant to express her sentiments with facial expressions, Nina frowned. The Count elaborated. “The principle here is that a new generation owes a measure of thanks to every member of the previous generation. Our elders planted fields and fought in wars; they advanced the arts and sciences, and generally made sacrifices on our behalf. So by their efforts, however humble, they have earned a measure of our gratitude and respect.”

Page 871

With so little to do and all the time in the world to do it, the Count’s peace of mind continued to be threatened by a sense of ennui—that dreaded mire of the human emotions. And if this is how desultory one feels after three weeks, reflected the Count, then how desultory can one expect to feel after three years?

Note: Man, that’s so true. “So little to do and all the time in the world to do it” - a terrible fate.

Page 021

But Fortune does favor the bold. So, while the next swing of the hammer glanced off the nail’s head, on the third the Count hit home; and by the second nail, he had recovered the rhythm of set, drive, and sink—that ancient cadence which is not to be found in quadrilles, or hexameters, or in Vronsky’s saddlebags!

Note: Claude explained this analogy

This passage is making a playful literary reference linking different types of rhythms. Let me break it down:

The basic rhythm being described is the three-part rhythm of hammering a nail:

- Set (position the nail)

- Drive (swing the hammer)

- Sink (the nail goes in)

The narrator then contrasts this simple, primal rhythm with three other types of rhythm that are more refined or sophisticated:

- Quadrilles (a formal French dance in four beats)

- Hexameters (a six-beat poetic meter used in classical epics)

- Vronsky’s saddlebags (this is a reference to Count Vronsky from Tolstoy’s “Anna Karenina” - an aristocratic cavalry officer known for his refined horsemanship)

The humor and meaning come from suggesting that this basic manual labor rhythm is something more authentic or fundamental than these more cultured/aristocratic forms of rhythm. It’s particularly ironic since it appears the person doing the hammering is a Count himself, suggesting he’s discovering something elemental that his usual refined lifestyle doesn’t provide.

The mention of Vronsky’s saddlebags specifically evokes the contrast between natural/practical rhythm (hammering) versus learned/artificial rhythm (formal horsemanship), with a hint of gentle mockery toward aristocratic refinement.

Page 026

His work completed, the Count sat down in one of the high-back chairs and felt an almost surprising sense of bliss. The Count’s bedroom and this improvised study had identical dimensions, and yet, they exerted a completely different influence on his mood. To some degree, this difference stemmed from the manner in which the two rooms had been furnished. For while the room next door—with its bed, bureau, and desk—remained a realm of practical necessities, the study—with its books, the Ambassador, and Helena’s portrait—had been furnished in a manner more essential to the spirit. But in all likelihood, a greater factor in the difference between the two rooms was their provenance. For if a room that exists under the governance, authority, and intent of others seems smaller than it is, then a room that exists in secret can, regardless of its dimensions, seem as vast as one cares to imagine.

Note: This resonates with me deeply. Personally I would prefer having a secret room that no one else knew about to the lavish rooms he had previously. Truly A Room Of One’s Own.

Page 033

Rising from his chair, the Count took up the largest of the ten volumes that he had retrieved from the basement. True, it would not be a new venture for him. But need it be? Could one possibly accuse him of nostalgia or idleness, of wasting his time simply because he had read the story two or three times before? Sitting back down, the Count put one foot on the edge of the coffee table and tilted back until his chair was balanced on its two hind legs, then he turned to the opening sentence: All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. “Marvelous,” said the Count.

Note: Nee padi thalai, nothing wrong re-reading the work of a 🐐

Page 213

“Naturally, I have little choice but to insist that my staff refrain from using such terms when addressing you. After all, I think we can agree without exaggeration or fear of contradiction that the times have changed.” In concluding thus, the manager looked to the Count so hopefully, that the Count took immediate pains to reassure him. “It is the business of the times to change, Mr. Halecki. And it is the business of gentlemen to change with them.” The manager looked to the Count with an expression of profound gratitude—that someone should understand what he had said so perfectly no further explication was required.

Note: Interactions like these really make him so likeable.

Page 233

For the times do, in fact, change. They change relentlessly. Inevitably. Inventively. And as they change, they set into bright relief not only outmoded honorifics and hunting horns, but silver summoners and mother-of-pearl opera glasses and all manner of carefully crafted things that have outlived their usefulness.

Note: Wistful.

Page 294

As such, the two young men hardly seemed fated for friendship. But Fate would not have the reputation it has if it simply did what it seemed it would do. Sure enough, while Mikhail was prone to throw himself into a scrape at the slightest difference of opinion, regardless of the number or size of his opponents, it just so happened that Count Alexander Rostov was prone to leap to the defense of an outnumbered man regardless of how ill conceived his cause. Thus, on the fourth day of their first year, the two students found themselves helping each other up off the ground, as they wiped the dust from their knees and the blood from their lips.

Note: Love that description of Fate.

Page 399

“But what of poetry? you ask. What of the written word? Well, I can assure you that it too is keeping pace. Once fashioned from bronze and iron, it is now being fashioned from steel. No longer an art of quatrains and dactyls and elaborate tropes, our poetry has become an art of action. One that will speed across the continents and transmit music to the stars!” Had the Count overheard such a speech spilling forth from a student in a coffeehouse, he might have observed with a glint in his eye that, apparently, it was no longer enough for a poet to write verse. Now, a poem must spring from a school with its own manifesto and stake its claim on the moment by means of the first-person plural and the future tense, with rhetorical questions and capital letters and an army of exclamation points! And above all else, it must be novaya.

Note: The section that follows about being out of step with the times is well written.

Page 444

troika

Note: TIL the first meaning of this word

troika /ˈtrɔɪkə/ I. noun 1. a Russian vehicle pulled by a team of three horses abreast. 2. a team of three horses for a troika. 3. a group of three people working together, especially in an administrative or managerial capacity. – origin Russian, from troe ‘set of three’.

Page 507

“By broadening your horizons,” he ventured, “what I meant is that education will give you a sense of the world’s scope, of its wonders, of its many and varied ways of life.” “Wouldn’t travel achieve that more effectively?” “Travel?” “We are talking about horizons, aren’t we? That horizontal line at the limit of sight? Rather than sitting in orderly rows in a schoolhouse, wouldn’t one be better served by working her way toward an actual horizon, so that she could see what lay beyond it? That’s what Marco Polo did when he traveled to China. And what Columbus did when he traveled to America. And what Peter the Great did when he traveled through Europe incognito!” Nina paused to take a great mouthful of the chocolate, and when the Count appeared about to reply she waved her spoon to indicate that she was not yet finished. He waited attentively for her to swallow. “Last night my father took me to Scheherazade.” “Ah,” the Count replied (grateful for the change of subject). “ Rimsky-Korsakov at his best.” “Perhaps. I wouldn’t know. The point is: According to the program, the composition was intended to ‘enchant’ the listeners with ‘the world of the Arabian Nights.’ ” “That realm of Aladdin and the lamp,” said the Count with a smile. “Exactly. And, in fact, everyone in the theater seemed utterly enchanted.” “Well, there you are.” “And yet, not one of them has any intention of going to Arabia—even though that is where the lamp is.” By some extraordinary conspiracy of fate, at the very instant Nina made this pronouncement, the accordion player concluded an old favorite and the sparsely populated room broke into applause. Sitting back, Nina gestured to her fellow customers with both hands as if their ovation were the final proof of her position. It is the mark of a fine chess player to tip over his own king when he sees that defeat is inevitable, no matter how many moves remain in the game.

Note: Every interaction between them is magical

Page 568

Instead, he dutifully picked up the menu. Perhaps he imagined that the perfect dish would leap off the page and identify itself by name. But for a hopeful young man trying to impress a serious young woman, the menu of the Piazza was as perilous as the Straits of Messina. On the left was a Scylla of lower-priced dishes that could suggest a penny-pinching lack of flair; and on the right was a Charybdis of delicacies that could empty one’s pockets while painting one pretentious. The young man’s gaze drifted back and forth between these opposing hazards. But in a stroke of genius, he ordered the Latvian stew. While this traditional dish of pork, onions, and apricots was reasonably priced, it was also reasonably exotic; and it somehow harkened back to that world of grandmothers and holidays and sentimental melodies that they had been about to discuss when so rudely interrupted.

Note: Love the literary references

Page 671

Perhaps what stirred the Count were these far-flung figures sharing in the fellowship of the season despite their lives of hard labor in inhospitable climes. Perhaps it was the sight earlier in the evening of that modern young couple proceeding toward romance in the age-old fashion. Perhaps it was the chance meeting with Nikolai, who, despite his heritage, seemed to be finding a place for himself in the new Russia. Or perhaps it was the utterly unanticipated blessing of Nina’s friendship. Whatever the cause, when the Count closed his book and turned out the light, he fell asleep with a great sense of well-being. But had the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come suddenly appeared and roused the Count to give him a glimpse of the future, he would have seen that his sense of well-being had been premature. For less than four years later, after another careful accounting of the twice-tolling clock’s twelve chimes, Alexander Ilyich Rostov would be climbing to the roof of the Metropol Hotel in his finest jacket and gamely approaching its parapet in order to throw himself into the street below.

Note: So bittersweet.

Page 699

For after all, if attentiveness should be measured in minutes and discipline measured in hours, then indomitability must be measured in years. Or, if philosophical investigations are not to your taste, then let us simply agree that the wise man celebrates what he can.

Page 880

And with that disarming memory, Anna Urbanova was suddenly describing how as a girl she would steal away from her mother at dusk and wind her way down the sloping streets of her village so that she could meet her father on the beach and help him mend his nets. And as she talked, the Count had to acknowledge once again the virtues of withholding judgment. After all, what can a first impression tell us about someone we’ve just met for a minute in the lobby of a hotel? For that matter, what can a first impression tell us about anyone? Why, no more than a chord can tell us about Beethoven, or a brushstroke about Botticelli. By their very nature, human beings are so capricious, so complex, so delightfully contradictory, that they deserve not only our consideration, but our reconsideration—and our unwavering determination to withhold our opinion until we have engaged with them in every possible setting at every possible hour.

Note: I would do well to remember and practice this.

Page 899

“According to local lore, hidden deep within the forest was a tree with apples as black as coal—and if you could find this tree and eat of its fruit, you could start your life anew.” The Count took a generous drink of the Montrachet, pleased to have summoned this little folktale from the past. “So would you?” the actress asked. “Would I what?” “If you found that apple hidden in the forest, would you take a bite?” The Count put his glass on the table and shook his head. “There’s certainly some allure to the idea of a fresh start; but how could I relinquish my memories of home, of my sister, of my school years.” The Count gestured to the table. “How could I relinquish my memory of this?” And Anna Urbanova, having put her napkin on her plate and pushed back her chair, came round the table, took the Count by the collar, and kissed him on the mouth.

Note: The whole evening before, the dismissal after, masterfully written.

Page 106

Now, when a man has been underestimated by a friend, he has some cause for taking offense—since it is our friends who should overestimate our capacities. They should have an exaggerated opinion of our moral fortitude, our aesthetic sensibilities, and our intellectual scope. Why, they should practically imagine us leaping through a window in the nick of time with the works of Shakespeare in one hand and a pistol in the other! But in this particular instance, the Count had to admit he had little grounds for taking offense. Because, for the life of him, he could not imagine from what dark corner of his adolescent mind this extraordinary fact had materialized.

Page 177

décolletage

Note: New word!

Page 269

Whichever wine was within, it was decidedly not identical to its neighbors. On the contrary, the contents of the bottle in his hand was the product of a history as unique and complex as that of a nation, or a man. In its color, aroma, and taste, it would certainly express the idiosyncratic geology and prevailing climate of its home terrain. But in addition, it would express all the natural phenomena of its vintage. In a sip, it would evoke the timing of that winter’s thaw, the extent of that summer’s rain, the prevailing winds, and the frequency of clouds. Yes, a bottle of wine was the ultimate distillation of time and place; a poetic expression of individuality itself. Yet here it was, cast back into the sea of anonymity, that realm of averages and unknowns.

Note: I don’t even like wine and I’m moved by this

Page 275

And suddenly, the Count had his own moment of lucidity. Just as Mishka had come to understand the present as the natural by-product of the past, and could see with perfect clarity how it would shape the future, the Count now understood his place in the passage of time. As we age, we are bound to find comfort from the notion that it takes generations for a way of life to fade. We are familiar with the songs our grandparents favored, after all, even though we never danced to them ourselves. At festive holidays, the recipes we pull from the drawer are routinely decades old, and in some cases even written in the hand of a relative long since dead. And the objects in our homes? The oriental coffee tables and well-worn desks that have been handed down from generation to generation? Despite being “out of fashion,” not only do they add beauty to our daily lives, they lend material credibility to our presumption that the passing of an era will be glacial. But under certain circumstances, the Count finally acknowledged, this process can occur in the comparative blink of an eye. Popular upheaval, political turmoil, industrial progress—any combination of these can cause the evolution of a society to leapfrog generations, sweeping aside aspects of the past that might otherwise have lingered for decades. And this must be especially so, when those with newfound power are men who distrust any form of hesitation or nuance, and who prize self-assurance above all. For years now, with a bit of a smile, the Count had remarked that this or that was behind him—like his days of poetry or travel or romance. But in so doing, he had never really believed it. In his heart of hearts, he had imagined that, even if unattended to, these aspects of his life were lingering somewhere on the periphery, waiting to be recalled. But looking at the bottle in his hand, the Count was struck by the realization that, in fact, it was all behind him. Because the Bolsheviks, who were so intent upon recasting the future from a mold of their own making, would not rest until every last vestige of his Russia had been uprooted, shattered, or erased.

Note: This is so haunting. The moment of realisation, and how clearly he sees.

Page 307

In keeping with the fashion of the times, most of the Count’s school-mates had turned their backs on the church; but they had only done so in favor of alternative consolations. Some who preferred the clarity of science adhered to the ideas of Darwin, seeing at every turn the mark of natural selection; while others opted for Nietzsche and his eternal recurrence or Hegel and his dialectic—each system quite sensible, no doubt, when one had finally arrived at the one-thousandth page.

Page 330

with a young officer of the Hussars standing at the reins like a centurion in his chariot.

Note: The first discordant note - centurions didn’t ride chariots. They had fallen out of fashion.

Page 432

“All right. But had you come for something in particular?” “No,” the Count replied after a pause, “nothing in particular.” But as he turned toward the door, something did occur to him. “Nina …” She looked up from her work. “Even though these hypotheses have been tested over time, I think you were perfectly right to test them again.” Nina studied the Count for a moment. “Yes,” she said with a nod. “You have always known me the best.”

Note: I don’t know how to describe what I’m feeling.

Page 445

But if the Count took pride in knowing that everything was in order, he took comfort in knowing that the world would carry on without him—and, in fact, already had. The night before, he had happened to be standing at the concierge’s desk when Vasily produced a map of Moscow for one of the hotel’s guests. As Vasily drew a zigzagging line from the center of the city to the Garden Ring, more than half of the streets he named were unfamiliar to the Count. Earlier that day, Vasily had informed him that the famed blue-and-gold lobby of the Bolshoi had been painted over in white, while in the Arbat Andreyev’s moody statue of Gogol had been plucked from its pedestal and replaced with a more uplifting one of Gorky. Just like that, the city of Moscow could boast new street names, new lobbies, and new statues—and neither the tourists, the theatergoers, nor the pigeons seemed particularly put out.

Note: I asked about why the statues were replaced. Claude said:

This would have been an ideological choice reflecting the Soviet Union’s literary priorities. Nikolai Gogol, while a great Russian writer, was associated with the pre-revolutionary period and wrote satirical works that often dealt with the supernatural, bureaucratic absurdity, and the dark sides of Russian society. His work, while brilliant, wasn’t aligned with Soviet ideals of socialist realism.

Maxim Gorky, on the other hand, was considered the father of Soviet literature and socialist realism. He came from a working-class background, wrote about the proletariat, supported the Bolshevik revolution, and developed close ties with Lenin and Stalin. His work “The Mother” is often considered the first socialist realist novel. He represented the kind of literature the Soviet regime wanted to promote - works focusing on class struggle, the dignity of labor, and the revolution.

The replacement of Gogol’s statue with Gorky’s would have symbolized this shift in cultural values - moving from the complex, satirical, and sometimes mystical literature of imperial Russia to the more direct, proletarian-focused socialist realism of the Soviet era. It would have been part of a broader effort to reshape cultural memory and public spaces to reflect Soviet values.

The Soviet regime was very deliberate in how it used public art and monuments to promote its ideology. Replacing statues was a common way to literally concrete these changes in the cultural landscape.

Page 492

“Number one,” said the Count, adding a pause for dramatic effect: “Chekhov and Tolstoy.” The German let out a grunt. “Yes, yes. I know what you’re going to say: that every nation has its poets in the pantheon. But with Chekhov and Tolstoy, we Russians have set the bronze bookends on the mantelpiece of narrative. Henceforth, writers of fictions from wheresoever they hail, will place themselves on the continuum that begins with the one and ends with the other. For who, I ask you, has exhibited better mastery of the shorter form than Chekhov in his flawless little stories? Precise and uncluttered, they invite us into some corner of a household at some discrete hour in which the entire human condition is suddenly within reach, if heartbreakingly so. While at the other extreme: Can you conceive of a work greater in scope than War and Peace? One that moves so deftly from the parlor to the battlefield and back again? That so fully investigates how the individual is shaped by history, and history by the individual? In the generations to come, I tell you there will be no new authors to supplant these two as the alpha and omega of narrative.”

Note: I absolutely must read more of Chekhov and all of War and Peace. There is no way around it.

Page 598

“Alexander, I am sorry that this fellow died in battle; but I think I can safely say that you have assumed more than your share of guilt for these events.” “But there is one more event to relate: Ten years ago tomorrow, while I was biding my time in Paris, my sister died.” “Of a broken heart …?” “Young women only die of broken hearts in novels, Charles. She died of scarlet fever.” The presumptive earl shook his head in bewilderment. “But don’t you see?” explained the Count. “It is a chain of events. That night at the Novobaczkys’ when I magnanimously tore his marker, I knew perfectly well that word of the act would reach the Princess; and I took the greatest satisfaction in turning the tables on the cad. But if I had not so smugly put him in his place, he would not have pursued Helena, he would not have humiliated her, I would not have shot him, he might not have died in Masuria, and ten years ago I would have been where I belonged—at my sister’s side—when she finally breathed her last.”

Page 611

For one last time, the Count looked out upon that city that was and wasn’t his. Given the frequency of street lamps on major roads, he could easily identify the Boulevard and Garden Rings—those concentric circles at the center of which was the Kremlin and beyond which was all of Russia. As long as there have been men on earth, reflected the Count, there have been men in exile. From primitive tribes to the most advanced societies, someone has occasionally been told by his fellow men to pack his bags, cross the border, and never set foot on his native soil again. But perhaps this was to be expected. After all, exile was the punishment that God meted out to Adam in the very first chapter of the human comedy; and that He meted out to Cain a few pages later. Yes, exile was as old as mankind. But the Russians were the first people to master the notion of sending a man into exile at home. As early as the eighteenth century, the Tsars stopped kicking their enemies out of the country, opting instead to send them to Siberia. Why? Because they had determined that to exile a man from Russia as God had exiled Adam from Eden was insufficient as a punishment; for in another country, a man might immerse himself in his labors, build a house, raise a family. That is, he might begin his life anew. But when you exile a man into his own country, there is no beginning anew. For the exile at home—whether he be sent to Siberia or subject to the Minus Six—the love for his country will not become vague or shrouded by the mists of time. In fact, because we have evolved as a species to pay the utmost attention to that which is just beyond our reach, these men are likely to dwell on the splendors of Moscow more than any Muscovite who is at liberty to enjoy them.

Note: Beautiful section on the torture of exile.

Page 877

Concerned? Mishka would pine for Katerina the rest of his life! Never again would he walk Nevsky Prospekt, however they chose to rename it, without feeling an unbearable sense of loss. And that is just how it should be. That sense of loss is exactly what we must anticipate, prepare for, and cherish to the last of our days; for it is only our heartbreak that finally refutes all that is ephemeral in love.

Page 073

“To old times,” he said. “To old times,” she conceded with a laugh. And they emptied their glasses. When one experiences a profound setback in the course of an enviable life, one has a variety of options. Spurred by shame, one may attempt to hide all evidence of the change in one’s circumstances. Thus, the merchant who gambles away his savings will hold on to his finer suits until they fray, and tell anecdotes from the halls of the private clubs where his membership has long since lapsed. In a state of self-pity, one may retreat from the world in which one has been blessed to live. Thus, the long-suffering husband, finally disgraced by his wife in society, may be the one who leaves his home in exchange for a small, dark apartment on the other side of town. Or, like the Count and Anna, one may simply join the Confederacy of the Humbled. Like the Freemasons, the Confederacy of the Humbled is a close-knit brotherhood whose members travel with no outward markings, but who know each other at a glance. For having fallen suddenly from grace, those in the Confederacy share a certain perspective. Knowing beauty, influence, fame, and privilege to be borrowed rather than bestowed, they are not easily impressed. They are not quick to envy or take offense. They certainly do not scour the papers in search of their own names. They remain committed to living among their peers, but they greet adulation with caution, ambition with sympathy, and condescension with an inward smile. As the actress poured some more vodka, the Count looked about the room. “How are the dogs?” he asked. “Better off than I am.” “To the dogs then,” he said, lifting his glass. “Yes,” she agreed with a smile. “To the dogs.”

Page 112

Ah, you may say with a knowing smile. So that is how it happened. That is how she regained her footing… . But Anna Urbanova was a genuine artist trained on the stage. What is more, as a member of the Confederacy of the Humbled, she had become an actress who appeared on time, knew her lines, and never complained. And as official preference shifted toward movies with a sense of realism and a spirit of perseverance, there was often a role for a woman with seasoned beauty and a husky voice. In other words, there were many factors within and without Anna’s control that contributed to her resurgence. Perhaps you are still skeptical. Well then, what about you? No doubt there have been moments when your life has taken a bit of a leap forward; and no doubt you look back upon those moments with self-assurance and pride. But was there really no third party deserving of even a modicum of credit? Some mentor, family friend, or schoolmate who gave timely advice, made an introduction, or put in a complimentary word? So, let us not dissect the hows and whys. It is enough to know that Anna Urbanova was once again a star with a house on the Fontanka Canal and copper ovals nailed to her furniture; though now when she has guests, she greets them at the door.

Note: What the narrator says to the reader is completely correct. I feel that way myself, about where I am. My job wouldn’t exist without the giants who had built every part of the software and hardware stack. But every step I’ve taken forward, I’ve benefited from the right opportunity opening at the right time. From mentors who gave me good advice. From people who took a punt on me.

Page 322

“If I may be so bold, Osip Ivanovich: What is it exactly that you do as an officer of the Party?” “Let’s just say that I am charged with keeping track of certain men of interest.” “Ah. Well, I imagine that becomes rather easy to achieve when you place them under house arrest.” “Actually,” corrected Glebnikov, “it is easier to achieve when you place them in the ground… .” The Count conceded the point. “But by all accounts,” continued Glebnikov, “you seem to have reconciled yourself to your situation.” “As both a student of history and a man devoted to living in the present, I admit that I do not spend a lot of time imagining how things might otherwise have been. But I do like to think there is a difference between being resigned to a situation and reconciled to it.” Glebnikov let out a laugh and gave the table a light slap.

Note: I love that. Subtle distinction between resignation and reconciliation.

Page 357

So in 1928, the Foreign Press Office was opened anew on the top floor of a six-story walk-up conveniently located halfway between the Kremlin and the offices of the secret police—a spot that just happened to be across the street from the Metropol. Thus, on any given night you could now find fifteen members of the international press in the Shalyapin ready to bend your ear. And when there were no listeners to be found, they lined up at the bar like gulls on the rocks and squawked all at once. And then there was that extraordinary development of 1929. In April of that year, the Shalyapin suddenly had not one, not two, but three hostesses—all young, beautiful, and wearing black dresses hemmed above the knee. With what charm and elegance they moved among the patrons of the bar, gracing the air with their slender silhouettes, delicate laughter, and hints of perfume. If the correspondents at the bar were inclined to talk more than they listened, in an instance of perfect symbiosis the hostesses were inclined to listen more than they talked. In part, of course, this was because their jobs depended upon it. For once a week, they were required to visit a little gray building on the corner of Dzerzhinsky Street where some little gray fellow behind a little gray desk would record whatever they had happened to hear word for word.fn1

Note: We’re supposed to understand what Dzerzhinsky Street means. “Perfect symbiosis”.

Page 533

With an appropriate sense of ceremony, Andrey bowed from the waist to accept it. And when he set the four knives in motion, Emile leaned back in his chair and with a tear in his eye watched as his trusted blade tumbled effortlessly through space, feeling that this moment, this hour, this universe could not be improved upon.

Page 749

“Have you ever seen one of those before?” the Count asked with a backward gesture and a smile. “An elephant?” she asked. “Or a lamp?” The Count coughed. “I meant an elephant.” “Only in books,” she admitted a little sadly. “Ah. Well. It is a magnificent animal. A wonder of creation.” Sofia’s interest piqued, the Count launched into a description of the species, animating each of its characteristics with an illustrative flourish of the arms. “A native of the Dark Continent, the mature example can weigh over ten thousand pounds. Its legs are as thick as tree trunks, and it bathes itself by drawing water into its proboscis and spraying it into the air—” “So, you have seen one?” she interrupted brightly. “On the Dark Continent?” The Count fidgeted. “Not exactly on the Dark Continent …” “Then where?” “In various books …” “Oh,” said Sofia, bringing the topic to a close with the efficiency of the guillotine.

Note: A guillotine hahaha

Page 768

“She is no more than thirty pounds; no more than three feet tall; her entire bag of belongings could fit in a single drawer; she rarely speaks unless spoken to; and her heart beats no louder than a bird’s. So how is it possible that she takes up so much space?!” Over the years, the Count had come to think of his rooms as rather ample. In the morning, they easily accommodated twenty squats and twenty stretches, a leisurely breakfast, and the reading of a novel in a tilted chair. In the evenings after work, they fostered flights of fancy, memories of travel, and meditations on history all crowned by a good night’s sleep. Yet somehow, this little visitor with her kit bag and her rag doll had altered every dimension of the room. She had simultaneously brought the ceiling downward, the floor upward, and the walls inward, such that anywhere he hoped to move she was already there. Having roused himself from a fitful night on the floor, when the Count was ready for his morning calisthenics, she was standing in the calisthenics spot. At breakfast, she ate more than her fair share of the strawberries; then when he was about to dip his second biscuit in his second cup of coffee, she was staring at it with such longing that he had no choice but to ask if she wanted it. And when, at last, he was ready to lean back in his chair with his book, she was already sitting in it, staring up at him expectantly. But having caught himself waving his shaving brush emphatically at his own reflection, the Count stopped cold. Good God, he thought. Is it possible? Already? At the age of forty-eight? “Alexander Rostov, could it be that you have become settled in your ways?”

Note: I wonder when I will reach this stage. I wonder if I reached it already, considering how much I like routine.

Page 268

“And what has been the fallout of that?” Mishka demanded of the statue. All but ruined, Bulgakov hadn’t written a word in years. Akhmatova had put down her pen. Mandelstam, having already served his sentence, had apparently been arrested again. And Mayakovsky? Oh, Mayakovsky … Mishka pulled at the hairs of his beard. Back in ’22, how boldly he had predicted to Sasha that these four would come together to forge a new poetry for Russia. Improbably, perhaps. But in the end, that is exactly what they had done. They had created the poetry of silence. “Yes, silence can be an opinion,” said Mishka. “Silence can be a form of protest. It can be a means of survival. But it can also be a school of poetry—one with its own meter, tropes, and conventions. One that needn’t be written with pencils or pens; but that can be written in the soul with a revolver to the chest.”

Page 298

The Count was presumably right to be concerned for Nina, though we will never know for certain—for she did not return to the Metropol within the month, within the year, or ever again. In October, the Count made some efforts to discover her whereabouts, all of them fruitless. One assumes that Nina made her own efforts to communicate with the Count, but no word was forthcoming, and Nina Kulikova simply disappeared into the vastness of the Russian East.

Note: I wasn’t fucking ready for this, what the fuck. Bffr.

Page 308

Within the walls of a small, drab office in an especially bureaucratic branch of government, it is generally difficult to accurately imagine the world outside. But it is never hard to imagine what might occur to one’s career were one to seize the illegitimate daughter of a Politburo member and place her in a home. Such initiative would be rewarded with a blindfold and a cigarette.

Page 585

“A fifth contribution?” “Yes, a fifth contribution: The burning of Moscow.” The Count was taken aback. “You mean in 1812?” Mishka nodded. “Can you imagine the expression on Napoleon’s face when he was roused at two in the morning and stepped from his brand-new bedroom in the Kremlin only to find that the city he’d claimed just hours before had been set on fire by its citizens?” Mishka gave a quiet laugh. “Yes, the burning of Moscow was especially Russian, my friend. Of that there can be no doubt. Because it was not a discrete event; it was the form of an event. One example plucked from a history of thousands. For as a people, we Russians have proven unusually adept at destroying that which we have created.” Perhaps because of his limp, Mishka no longer got up to pace the room; but the Count could see that he was pacing it with his eyes. “Every country has its grand canvas, Sasha—the so-called masterpiece that hangs in a hallowed hall and sums up the national identity for generations to come. For the French it is Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People; for the Dutch, Rembrandt’s Night Watch; for the Americans, Washington Crossing the Delaware; and for we Russians? It is a pair of twins: Nikolai Ge’s Peter the Great Interrogating Alexei and Ilya Repin’s Ivan the Terrible and His Son. For decades, these two paintings have been revered by our public, praised by our critics, and sketched by our diligent students of the arts. And yet, what do they depict? In one, our most enlightened Tsar studies his oldest son with suspicion, on the verge of condemning him to death; while in the other, unflinching Ivan cradles the body of his eldest, having already exacted the supreme measure with a swing of the scepter to the head. “Our churches, known the world over for their idiosyncratic beauty, for their brightly colored spires and improbable cupolas, we raze one by one. We topple the statues of old heroes and strip their names from the streets, as if they had been figments of our imagination. Our poets we either silence, or wait patiently for them to silence themselves.” Mishka picked up his fork, stuck it in the untouched veal, and raised it in the air. “Do you know that back in ’30, when they announced the mandatory collectivization of farming, half our peasants slaughtered their own livestock rather than give them up to the cooperatives? Fourteen million head of cattle left to the buzzards and flies.” He gently returned the cut of meat to its plate, as if in a show of respect. “How can we understand this, Sasha? What is it about a nation that would foster a willingness in its people to destroy their own artworks, ravage their own cities, and kill their own progeny without compunction? To foreigners it must seem shocking. It must seem as if we Russians have such a brutish indifference that nothing, not even the fruit of our loins, is viewed as sacrosanct. And how that notion pained me. How it unsettled me. Exhausted as I was, the very thought of it could keep…

Page 713

His tone grew softer. “The Bolsheviks are not Visigoths, Alexander. We are not the barbarian hordes descending upon Rome and destroying all that is fine out of ignorance and envy. It is the opposite. In 1916, Russia was a barbarian state. It was the most illiterate nation in Europe, with the majority of its population living in modified serfdom: tilling the fields with wooden plows, beating their wives by candlelight, collapsing on their benches drunk with vodka, and then waking at dawn to humble themselves before their icons. That is, living exactly as their forefathers had lived five hundred years before. Is it not possible that our reverence for all the statues and cathedrals and ancient institutions was precisely what was holding us back?” Osip paused, taking a moment to refill their glasses with wine. “But where do we stand now? How far have we come? By marrying American tempo with Soviet aims, we are on the verge of universal literacy. Russia’s long-suffering women, our second serfdom, have been elevated to the status of equals. We have built whole new cities and our industrial production outpaces that of most of Europe.” “But at what cost?” Osip slapped the table. “At the greatest cost! But do you think the achievements of the Americans—envied the world over—came without a cost? Just ask their African brothers. And do you think the engineers who designed their illustrious skyscrapers or built their highways hesitated for one moment to level the lovely little neighborhoods that stood in their way? I guarantee you, Alexander, they laid the dynamite and pushed the plungers themselves. As I’ve said to you before, we and the Americans will lead the rest of this century because we are the only nations who have learned to brush the past aside instead of bowing before it. But where they have done so in service of their beloved individualism, we are attempting to do so in service of the common good.”

Note: Fantastic riposte

Page 122

It was Chopin. Opus 9, number 2, in E-flat major. As she completed the first iteration of the melody in a perfect pianissimo and transitioned to the second with its suggestion of rising emotional force, the Count took another two steps back and found himself sitting in a chair. Had he felt pride in Sofia before? Of course he had. On a daily basis. He was proud of her success in school, of her beauty, of her composure, of the fondness with which she was regarded by all who worked in the hotel. And that is how he could be certain that what he was experiencing at that moment could not be referred to as pride. For there is something knowing in the state of pride. Look, it says, didn’t I tell you how special she is? How bright? How lovely? Well, now you can see it for yourself. But in listening to Sofia play Chopin, the Count had left the realm of knowing and entered the realm of astonishment. On one level he was astonished by the revelation that Sofia could play the piano at all; on another, that she tackled the primary and subordinate melodies with such skill. But what was truly astonishing was the sensitivity of her musical expression. One could spend a lifetime mastering the technical aspects of the piano and never achieve a state of musical expression—that alchemy by which the performer not only comprehends the sentiments of the composer, but somehow communicates them to her audience through the manner of her play. Whatever personal sense of heartache Chopin had hoped to express through this little composition—whether it had been prompted by a loss of love, or simply the sweet anguish one feels when witnessing a mist on a meadow in the morning—it was right there, ready to be experienced to its fullest, in the ballroom of the Hotel Metropol one hundred years after the composer’s death. But how, the question remained, could a seventeen-year-old girl achieve this feat of expression, if not by channeling a sense of loss and longing of her own?

Page 806

When the Count had quietly closed the door, he turned to Anna, whose expression was unusually grave. “When did the Minister of Culture start taking a personal interest in Sofia?” he asked. “Tomorrow afternoon,” she replied. “At the latest.”

Page 912

And do you know, do you know that mankind can live without the Englishman, it can live without Germany, it can live only too well without the Russian man, it can live without science, without BREAD, and it only cannot live without beauty… . Demons Fyodor Dostoevsky (1872)

Page 592

Showing a sense of personal restraint that was almost out of character, the Count had restricted himself to two succinct pieces of parental advice. The first was that if one did not master one’s circumstances, one was bound to be mastered by them; and the second was Montaigne’s maxim that the surest sign of wisdom is constant cheerfulness.

Page 619

“Do you ever regret coming back to Russia?” she asked after a moment. “I mean after the Revolution.” The Count studied his daughter. If when Sofia had stepped out of Anna’s room in her blue dress, the Count had felt she was crossing the threshold into adulthood, then here was a perfect confirmation. For in both tone and intent, when Sofia posed this question she did not do so as a child asks a parent, but as one adult asks another about the choices he has made. So the Count gave the question its due consideration. Then he told her the truth: “Looking back, it seems to me that there are people who play an essential role at every turn. And I don’t just mean the Napoleons who influence the course of history; I mean men and women who routinely appear at critical junctures in the progress of art, or commerce, or the evolution of ideas—as if Life itself has summoned them once again to help fulfill its purpose. Well, since the day I was born, Sofia, there was only one time when Life needed me to be in a particular place at a particular time, and that was when your mother brought you to the lobby of the Metropol. And I would not accept the Tsarship of all the Russias in exchange for being in this hotel at that hour.” Sofia rose from the table to give her father a kiss on the cheek.

Page 965

On the night before she had left Moscow, when Sofia had expressed her distress at what her father wanted her to do, he had attempted to console her with a notion. He had said that our lives are steered by uncertainties, many of which are disruptive or even daunting; but that if we persevere and remain generous of heart, we may be granted a moment of supreme lucidity—a moment in which all that has happened to us suddenly comes into focus as a necessary course of events, even as we find ourselves on the threshold of a bold new life that we had been meant to lead all along. When her father had made this claim, it had seemed so outlandish, so overblown that it had not assuaged Sofia’s distress in the least. But turning in place on the Place de la Concorde, seeing the Arc de Triomphe, and the Eiffel Tower, and the Tuileries, and the cars and Vespas zipping around the great obelisk, Sofia had an inkling of what her father had been trying to say.

Page 230

If one has been absent for decades from a place that one once held dear, the wise would generally counsel that one should never return there again. History abounds with sobering examples: After decades of wandering the seas and overcoming all manner of deadly hazards, Odysseus finally returned to Ithaca, only to leave it again a few years later. Robinson Crusoe, having made it back to England after years of isolation, shortly thereafter set sail for that very same island from which he had so fervently prayed for deliverance. Why after so many years of longing for home did these sojourners abandon it so shortly upon their return? It is hard to say. But perhaps for those returning after a long absence, the combination of heartfelt sentiments and the ruthless influence of time can only spawn disappointments. The landscape is not as beautiful as one remembered it. The local cider is not as sweet. Quaint buildings have been restored beyond recognition, while fine old traditions have lapsed to make way for mystifying new entertainments. And having imagined at one time that one resided at the very center of this little universe, one is barely recognized, if recognized at all. Thus do the wise counsel that one should steer far and wide of the old homestead. But no counsel, however well grounded in history, is suitable for all. Like bottles of wine, two men will differ radically from each other for being born a year apart or on neighboring hills. By way of example, as this traveler stood before the ruins of his old home, he was not overcome by shock, indignation, or despair. Rather, he exhibited the same smile, at once wistful and serene, that he had exhibited upon seeing the overgrown road. For as it turns out, one can revisit the past quite pleasantly, as long as one does so expecting nearly every aspect of it to have changed.

Note: So beautiful