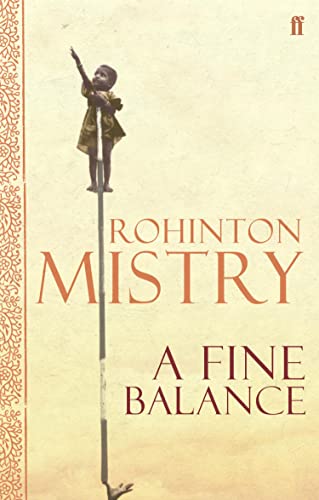

A Fine Balance

by Rohinton Mistry

- Author:

- Rohinton Mistry

- Status:

- Done

- Format:

- eBook

- Reading Time:

- 9:05

- Genres:

- Fiction , Historical Fiction , India , Book Club , Indian Literature , Literary Fiction , Historical

- Pages:

- 624

- Highlights:

- 38

Review

This follows the lives of 4 ordinary people during the Emergency of the 1970s. It gave me a fresh perspective on a difficult time in India’s history, as well an appreciation of the difficulties faced by Indians less privileged than me. Reading this drained me emotionally, but it was worth it.

Highlights

Page 21

‘You have always had the habit of blurting whatever comes into your loose mouth. But you are no longer a child. Someone has to teach you respect.’ He sighed, ‘It is my duty, I suppose‚’ and without warning he began slapping her. He stopped when a cut opened her lower lip. ‘You pig!’ she wept. ‘You want to make me look ugly like you!’ Whereupon, he got a ruler and whacked her wherever he could, as she ran around trying to escape the blows. For once, Mrs. Shroff noticed that something was wrong. ‘Why are you crying, my daughter?’ ‘That stupid Dracula! He hit me and made me bleed!’ ‘Tch-tch, my poor child.’ She hugged Dina and returned to her seat by the window. Two days after this row, Nusswan tried to make peace by bringing Dina a collection of ribbons. ‘They will look lovely in your plaits‚’ he said. She went to her school satchel, got out her arts-and-crafts scissors, and snipped the ribbons into small pieces.

Note: Abusive relationship

Page 25

Cooped up inside the flat, Nusswan lamented the country’s calamity, grumbling endlessly. ‘Every day I sit at home, I lose money. These bloody uncultured savages don’t deserve independence. If they must hack one another to death, I wish they would go somewhere else and do it quietly. In their villages, maybe. Without disturbing our lovely city by the sea.’

Note: Oh I’m so inconvenienced by your struggle for freedom

Page 26

After the first month’s prayer ceremonies for Mrs. Shroff were completed, Nusswan decided there was no point in Dina matriculating. Her last report card was quite wretched. She would have been kept back were it not for the principal who, loyal to the memory of Dr. Shroff, preferred to see the marks as a temporary aberration. ‘Very decent of Miss Lamb to promote you,’ said Nusswan. ‘But the fact remains that your results are hopeless. I’m not going to waste money on school fees for another year.’ ‘You make me clean and scrub all the time, I cannot study for even one hour a day! What do you expect?’ ‘Don’t make excuses. A strong young girl, doing a little housework – What’s that got to do with studying? Do you know how fortunate you are? There are thousands of poor children in the city, doing boot-polishing at railway stations, or collecting papers, bottles, plastic – plus going to school at night. And you are complaining? What’s lacking in you is the desire for education. This is it, enough schooling for you.’

Note: I wonder how many women lost schooling like this - “you need to spend hours doing chores. Oh look, your grades dropped, what a shocker. That’s it no more school. You get married.”

Page 49

‘Yes,’ said Dina, ‘but my rent –’ ‘Don’t worry, I’ll pay it,’ said Nusswan. ‘And my lawyer will reply to this letter.’ He was thinking ahead: sooner or later Dina would remarry. At that juncture, it would be very unfortunate if the lack of a flat were to pose an impediment. He definitely would not want the couple living with him. That would be a blueprint for friction and strife.

Note: Her work was undervalued. She could have paid her own rent if she had gotten the salary of a maid or nanny. But she did that for “free” and then had to depend on handouts. My blood boils at such injustice.

Page 59

But when they ventured into the private garden of intimacy, it was a troubled relationship. There were certain things she could not bring herself to do. The bed – any bed – was out of bounds, sacred and reserved for married couples only. So they used a chair. Then one day, as she swung a leg over to straddle Fredoon, her action suddenly resurrected the image of Rustom flinging his leg over his bicycle. Now the chair, like the bed, was no longer possible.

Note: Arbitrary rules people create to make their lives harder. But who knows, maybe it’s better this way even though I can’t see it

Page 67

So Dina continued to distribute her name and address at tailors’ shops, going further afield, taking the train to the northern suburbs, to parts of the city she had never seen in all her forty-two years. Her progress was frequently held up when traffic was blocked by processions and demonstrations against the government. Sometimes, from the upper deck of the bus, she had a good view of the tumultuous crowds. The banners and slogans accused the Prime Minister of misrule and corruption, calling on her to resign in keeping with the court judgment finding her guilty of election malpractice.

Note: I like how the historical setting is weaved in

Page 70

Then he brightened suddenly. ‘The thing is, you have come to the right place. I have two wonderful tailors for you. I will send them tomorrow.’ ‘Really?’ she asked, sceptical about the change of heart. ‘Oh yes, two beautiful tailors, or my name is not Nawaz. The thing is, they don’t have their own shop, they go out and work. But they are very skilled. You will be so happy with them.’

Note: Or my name is not … very Indian thing to say

Page 73

This event alone would have been enough to ensure Mrs. Gupta’s happiness, but there were more glad tidings; minor irritants in her life were also being eradicated – the Prime Minister’s declaration yesterday of the Internal Emergency had incarcerated most of the parliamentary opposition, along with thousands of trade unionists, students, and social workers. ‘Isn’t that good news?’ she sparkled with joy. Dina nodded, doubtful. ‘I thought the court found her guilty of cheating in the election.’ ‘No, no, no!’ said Mrs.Gupta. ‘That is all rubbish, it will be appealed. Now all those troublemakers who accused her falsely have been put in jail. No more strikes and morchas and silly disturbances.’

Note: People supported the Emergency as long as they weren’t affected personally

Page 75

‘Dinabai, what is this Emergency we hear about?’ ‘Government problems – games played by people in power. It doesn’t affect ordinary people like us.’ ‘That’s what I said,’ murmured Omprakash. ‘My uncle was simply worrying.’

Page 95

The Chamaars skinned the carcass, ate the meat, and tanned the hide, which was turned into sandals, whips, harnesses, and waterskins. Dukhi learned to appreciate how dead animals provided his family’s livelihood. And as he mastered the skills, imperceptibly but relentlessly Dukhi’s own skin became impregnated with the odour that was part of his father’s smell, the leather-worker’s stink that would not depart even after he had washed and scrubbed in the all-cleansing river. Dukhi did not realize his pores had imbibed the fumes till his mother, hugging him one day, wrinkled her nose and said, her voice a mix of pride and sorrow, ‘You are becoming an adult, my son, I can sniff the change.’ For a while afterwards, he was constantly lifting his forearm to his nose to see if the odour still lingered. He wondered if flaying would get rid of it. Or did it go deeper than skin? He pricked himself to smell his blood but the test was inconclusive, the little ruby at his fingertip being an insufficient sample. And what about muscle and bone, did the stink lurk in them too? Not that he wanted it gone; he was happy then to smell like his father.

Page 96

While Dukhi’s father ate, he repeated for his wife everything he had learned that day. ‘The Pandit’s cow is not healthy. He is trying to sell it before it dies.’ ‘Who gets it if it dies? Is it your turn yet?’ ‘No, it is Bhola’s turn. But where he was working, they accused him of stealing. Even if the Pandit lets him have the carcass, he will need my help – they chopped off his left-hand fingers today.’ ‘Bhola is lucky,’ said Dukhi’s mother. ‘Last year Chhagan lost his hand at the wrist. Same reason.’ Dukhi’s father took a drink of water and swirled it around in his mouth before swallowing. He ran the back of his hand across his lips. ‘Dosu got a whipping for getting too close to the well. He never learns.’ Eating in silence for a while, he listened to the frogs bellowing in the humid night, then asked his wife, ‘You are not having anything?’ ‘It’s my fasting day.’ In her code, it meant there wasn’t enough food. Dukhi’s father nodded, taking another mouthful. ‘Have you seen Buddhu’s wife recently?’ She shook her head. ‘Not since many days.’ ‘And you won’t for many more. She must be hiding in her hut. She refused to go to the field with the zamindar’s son, so they shaved her head and walked her naked through the square.’

Note: Reading this makes my blood boil

Page 97

Soon after Dukhi Mochi turned eighteen, his parents married him to a Chamaar girl named Roopa, who was fourteen. She gave birth to three daughters during their first six years together. None survived beyond a few months. Then they had a son, and the families rejoiced greatly. The child was called Ishvar, and Roopa watched over him with the special ardour and devotion she had learned was reserved for male children. She made sure he always had enough to eat. Going hungry herself was a matter of course – that she often did even to keep Dukhi fed. But for this child she did not hesitate to steal either. And there was not a mother she knew who would not have taken the same risk for her own son. After her milk went dry, Roopa began nocturnal visits to the cows of various landowners. While Dukhi and the child slept, she crept out of the hut with a small brass haandi, some time between midnight and cockcrow. The pitch-black path she walked without stumbling had been memorized during the day, for a lamp was too dangerous. The darkness brushed her cheeks like a cobweb. Sometimes the cobwebs were real. She took only a little from each cow; thus, the owner would not sense a decrease in the yield. When Dukhi saw the milk in the morning, he understood. If he awoke in the night as she was leaving, he said nothing, and lay shivering till she returned. He often wondered whether he should offer to go instead.

Note: Mothers love

Page 100

Fortunately, the majority of the upper castes were content to wax philosophic about the problem of fallow wombs and leave it at that. They said it was obvious the world was passing through Kaliyug, through the Age of Darkness, and sonless wives were not the only aberration in the cosmic order. ‘Witness the recent drought‚’ they said. ‘A drought that came even though we performed all the correct pujas. And when the rains fell, they fell in savage torrents; remember the floods, the huts that were washed away. And what about the two-headed calf in the neighbouring district?’ No one in the village had seen the two-headed calf, for the distance was great, and it was not possible to make the journey and return by nightfall to the safety of their huts. But they had all heard about the monstrous birth. ‘Yes, yes‚’ they agreed. ‘The Pandits are absolutely correct. It is Kaliyug that is the cause of our troubles.’ The remedy, the Pandits advised, was to be more vigilant in the observance of the dharmic order. There was a proper place for everyone in the world, and as long as each one minded his place, they would endure and emerge unharmed through the Darkness of Kaliyug. But if there were transgressions – if the order was polluted – then there was no telling what calamities might befall the universe. After this consensus was reached, the village saw a sharp increase in the number of floggings meted out to members of the untouchable castes, as the Thakurs and Pandits tried to whip the world into shape. The crimes were varied and imaginative: a Bhunghi had dared to let his unclean eyes meet Brahmin eyes; a Chamaar had walked on the wrong side of the temple road and defiled it; another had strayed near a puja that was in progress and allowed his undeserving ears to overhear the sacred shlokas; a Bhunghi child had not erased her footprints cleanly from the dust in a Thakur’s courtyard after finishing her duties there – her plea that her broom was worn thin was unacceptable.

Note: The injustice

Page 105

Two days later he told her, his bitterness overflowing like the foul ooze from his foot. He had not minded when he had been beaten that time for the straying goats. It had been his fault, he had fallen asleep. But this time he had done nothing wrong. He had worked hard all day, yet he had been thrashed and cheated of his payment. ‘On top of that, my foot is crushed‚’ he said. ‘I could kill that Thakur. Nothing but a lowly thief. And they are all like that. They treat us like animals. Always have, from the days of our forefathers.’

Page 108

The news was of the same type that Dukhi had heard evening after evening during his childhood; only the names were different. For walking on the upper-caste side of the street, Sita was stoned, though not to death – the stones had ceased at first blood. Gambhir was less fortunate; he had molten lead poured into his ears because he ventured within hearing range of the temple while prayers were in progress. Dayaram, reneging on an agreement to plough a landlord’s field, had been forced to eat the landlord’s excrement in the village square. Dhiraj tried to negotiate in advance with Pandit Ghanshyam the wages for chopping wood, instead of settling for the few sticks he could expect at the end of the day; the Pandit got upset, accused Dhiraj of poisoning his cows, and had him hanged.

Page 115

‘Ashraf Chacha is going to turn you into tailors like himself. From now on, you are not cobblers – if someone asks your name, don’t say Ishvar Mochi or Narayan Mochi. From now on you are Ishvar Darji and Narayan Darji.’

Page 120

The family’s excitement continued the next morning. The boys had brought a tape measure, a blank page, and a pencil from Muzaffar Tailoring, and wanted to measure their parents. Ashraf had taught them a diagrammatic code for the constantly used words like neck, waist, chest, and sleeve. The boys could not reach high enough, so the two clients had to bend down or sit on the floor for some of the measurements: first their mother, and then their father. While they were recording Dukhi’s sizes, Roopa called her friends from nearby huts to watch. Now Ishvar grew self-conscious and smiled shyly, but Narayan flourished the tape and made his gestures more expansive, enjoying the attention. Everyone clapped with delight when they finished. In the evening, Dukhi borrowed the piece of paper to show to his friends under the tree by the river. He carried it about with him for the rest of the week.

Note: Made me tear up on the tube

Page 130

Now the hardware-store owner opened his upstairs window and shouted, ‘What’s going on? Why are you harassing Hindu boys? Have you run out of Muslims?’ ‘And who are you?’ they shouted back. ‘Who am I? I am your father and your grandfather! That’s who I am! And also the owner of this hardware store! If I give the word, the whole street will unite as one to make mincemeat of you! Don’t you have somewhere else to go?’

Note: “Father and grandfather” sounds so weird in English

Page 143

On election day the eligible voters in the village lined up outside the polling station. As usual, Thakur Dharamsi took charge of the voting process. His system, with the support of the other landlords, had been working flawlessly for years. The election officer was presented with gifts and led away to enjoy the day with food and drink. The doors opened and the voters filed through. ‘Put out your fingers,’ said the attendant monitoring the queue. The voters complied. The clerk at the desk uncapped a little bottle and marked each extended finger with indelible black ink, to prevent cheating. ‘Now put your thumbprints over here,’ said the clerk. They placed their thumbprints on the register to say they had voted, and departed.

Note: “Largest democracy” ladies and gentlemen

Page 172

Foreign women enjoy wearing other people’s hair. Men also, especially if they are bald. In foreign countries they fear baldness. They are so rich in foreign countries, they can afford to fear all kinds of silly things.’

Page 208

And so,

Page 227

‘Not at all – quite the contrary.’ He hesitated, ‘It’s such a long story.’ ‘But we have lots of time.’ encouraged Maneck. ‘It’s such a long journey.’

Note: He wrote a book called Such a Long Journey. He likes the phrase

Page 231

The proofreader nodded, ‘You see, you cannot draw lines and compartments, and refuse to budge beyond them. Sometimes you have to use your failures as stepping-stones to success. You have to maintain a fine balance between hope and despair.’ He paused, considering what he had just said. ‘Yes,’ he repeated. ‘In the end, it’s all a question of balance.’

Note: Title Drop!

Page 241

It was not long before the reason for the uproar was learned by the entire dining hall: a vegetarian student had discovered a sliver of meat floating in a supposedly vegetarian gravy of lentils. The news spread, about the bastard caterer who was toying with their religious sentiments, trampling on their beliefs, polluting their beings, all for the sake of fattening his miserable wallet. Within minutes, every vegetarian living in the hostel had descended on the canteen, raging about the duplicity. Some of them seemed on the verge of a breakdown, screaming incoherently, going into convulsions, poking fingers down their throats to regurgitate the forbidden substance. Several succeeded in vomiting up their dinners. But there were no fingers long enough to reach the meals digested since the beginning of term. That vile stuff was already absorbed to become part of their own marrow, and the cause of their anguish. They retched and spat and groaned, and spun in circles, holding their heads, crying about the calamity, unwilling to acknowledge that their stomachs were empty, there was nothing left to bring up.

Note: My heart bleeds for them

Page 247

Two professors who chose to denounce the campus goon squads were taken away by plainclothesmen for anti-government activities, under the Maintenance of Internal Security Act. Their colleagues did not interfere on their behalf because MISA allowed imprisonment without trial, and it was a well-known fact that those who questioned MISA sooner or later answered to MISA; it was safer not to tangle with something so pernicious.

Note: I wonder when Modiji will pass this bill.

Page 258

‘Ask your men with the cameras to pull some photos of our lovely houses, our healthy children! Show that to the Prime Minister!’

Note: Pull some photos

Page 298

‘Haven’t seen you for some time,’ he said. ‘Any news of Nawaz since the police took him?’ ‘Police? For what?’ ‘Smuggling gold from the Gulf.’ ‘Really? Was he?’ ‘Of course not. He was just a tailor, like you.’ But Nawaz had quarrelled with somebody whose daughter was getting married. The man, well-connected, had given him a large assignment – wedding clothes for the entire family. After the wedding he refused to pay, claiming that the clothes fit badly. Nawaz kept asking for his money to no avail, then found out where the man’s office was. He showed up there, to embarrass him among his colleagues. ‘And that was a big mistake. The bastard took his revenge. That same night the police came for Nawaz.’ ‘Just like that? How can they put an innocent man in jail? The other fellow is the crook.’ ‘With the Emergency, everything is upside-down. Black can be made white, day turned into night. With the right influence and a little cash, sending people to jail is very easy. There’s even a new law called MISA to simplify the whole procedure.’ ‘What’s MISA?’ ‘Maintenance of … something, and Security … something, I’m not sure.’ The tailors finished the tea and departed with their loads. ‘Poor Nawaz,’ said Ishvar. ‘Wonder if he was really up to something crooked.’ ‘Must have,’ said Om. ‘They don’t send people to jail for nothing. I never liked him. But now what?’

Note: They don’t send people to jail for nothing

Page 304

‘You could have let them stay at least tonight. They could have slept in my room.’ ‘That would be trouble with a capital t. One night is enough for the landlord to bring a case against me.’ ‘And what about the trunk? Why can’t you keep it for them?’ ‘What’s this, a police interrogation? You’ve lived such a sheltered life, you’ve no idea what kind of crookedness exists in a city like this. A trunk, a bag, or even a satchel with just two pyjamas and a shirt is the first step into a flat. Personal items stored on the premises – that’s the most common way of staking a claim. And the court system takes years to settle the case, years during which the crooks are allowed to stay in the flat. Now I’m not saying Ishvar and Om came tonight with this plan in their heads. But how can I take the risk? What if they get the idea later from some rascal? Any trouble with the landlord means I have to ask for Nusswan’s help. My brother is absolutely unbearable. He would crow and crow about it.’

Note: Low trust society

Page 322

‘But please listen to me, no,’ he sniffed. ‘This beggar is useless in her condition.’ ‘Actually speaking, that’s not my concern. I have to follow orders.’ Tonight, Sergeant Kesar had decided he was going to tolerate no nonsense, his job was getting harder by the day. Gathering crowds for political rallies wasn’t bad. Rounding up MISA suspects was also okay. But demolishing hutment colonies, vendors’ stalls, jhopadpattis was playing havoc with his peace of mind. And prior to his superiors formulating this progressive new strategy for the beggary problem, he had had to dump pavement-dwellers in waste land outside the city. He used to return miserable from those assignments, get drunk, abuse his wife, beat his children. Now that his conscience was recuperating, he was not about to let this nose-dripping idiot complicate matters.

Note: Orders

Page 329

‘Yes babu, all very good,’ said the beggar. ‘But tell me, metal-collector, without legs or fingers, what could I do?’ ‘Don’t make excuses. In a huge city like this there is work even for a corpse. But you have to want it, and look for it seriously. You beggars create nuisance on the streets, then police make trouble for everyone. Even for us hardworking people.’

Page 336

How much Dina Aunty relished her memories. Mummy and Daddy were the same, talking about their yesterdays and smiling in that sad-happy way while selecting each picture, each frame from the past, examining it lovingly before it vanished again in the mist. But nobody ever forgot anything, not really, though sometimes they pretended, when it suited them. Memories were permanent. Sorrowful ones remained sad even with the passing of time, yet happy ones could never be recreated – not with the same joy. Remembering bred its own peculiar sorrow. It seemed so unfair: that time should render both sadness and happiness into a source of pain.

Page 342

‘Oh stop being silly,’ she said, draining the glass. ‘Let me tell you what I can see better. When I was twelve my father decided to go and work in an area of epidemic. It worried my mother very much. She wanted me to change his mind – you see, I was his favourite. Then my father died while working there. And my mother said if I had followed her advice I might have saved him.’ ‘That wasn’t fair.’ ‘It was and it wasn’t. Just like what you said.’ He understood.

Note: Nice callback

Page 372

‘Maybe,’ said Dina. ‘But I think the government should let homeless people sleep on the pavements. Then my tailors wouldn’t have disappeared and I wouldn’t have come here to bother you.’ Nusswan lifted his index finger and waggled it like a hyperactive windshield wiper. ‘People sleeping on pavements gives industry a bad name. My friend was saying last week – he’s the director of a multinational, mind you, not some small, two-paisa business – he was saying that at least two hundred million people are surplus to requirements, they should be eliminated.’ ‘Eliminated?’ ‘Yes. You know – got rid of. Counting them as unemployment statistics year after year gets us nowhere, just makes the numbers look bad. What kind of lives do they have anyway? They sit in the gutter and look like corpses. Death would be a mercy.’ ‘But how would they be eliminated?’ inquired Maneck in his most likeable, most deferential tone. ‘That’s easy. One way would be to feed them a free meal containing arsenic or cyanide, whichever is cost-effective. Lorries could go around to the temples and places where they gather to beg.’ ‘Do many business people think like this?’ asked Dina curiously. ‘A lot of us think like this, but until now we did not have the courage to say so. With the Emergency, people can freely speak their minds. That’s another good thing about it.’ ‘But the newspapers are censored,’ said Maneck. ‘Ah yes, yes,’ said Nusswan, at last betraying impatience. ‘And what’s so terrible about that? It’s only because the government does not want anything published which will alarm the public. It’s temporary – so lies can be suppressed and people can regain confidence. Such steps are necessary to preserve the democratic structure. You cannot sweep clean without making the new broom dirty.’ ‘I see,’ said Maneck. The bizarre aphorisms were starting to grate on him, but he did not possess the ammunition to launch even a modest counterattack.

Note: Nice how this meeting was arranged

Page 392

‘I returned straight to my supervisor and made a complaint. How could I produce results, I said, if the doctors killed the patients? But he said the man died because he was old, and the family was simply at all blaming the Family Planning Centre.’ ‘Goat-fucking bastard,’ said Om. ‘Exactly. But guess what else the supervisor told me. From now on my job would be easier, he said, because of a policy change.’ The new scheme had been explained to Rajaram – it was no longer necessary to sign up individuals for the operation. Instead, they were to be offered a free medical checkup. And it wasn’t to be viewed as lying, just a step towards helping people improve their lives. Once inside the clinic, isolated from the primitive influence of families and friends, they would quickly see the benefits of sterilization.

Page 472

She remembered the years when her nephews were small. What a time of fun it had been, but so brief. And how miserable they were when Nusswan and Ruby and she argued, and there was screaming and shouting. Not knowing whose side to take, whether to run to Daddy or to Aunty to plead for peace. In the end, she had missed out on so much. Their school years, report cards, prize distribution days, cricket matches, their first long trousers. Independence came at a high price: a debt with a payment schedule of hurt and regret. But the other option – under Nusswan’s thumb – was inconceivable.

Note: Good writing

Page 517

‘It’s a strange thing. When my Mumtaz was alive, I would sit alone all day, sewing or reading. And she would be by herself in the back, busy cooking and cleaning and praying. But there was no loneliness, the days passed easily. Just knowing she was there was enough. And now I miss her so much. What an unreliable thing is time – when I want it to fly, the hours stick to me like glue. And what a changeable thing, too. Time is the twine to tie our lives into parcels of years and months. Or a rubber band stretched to suit our fancy. Time can be the pretty ribbon in a little girl’s hair. Or the lines in your face, stealing your youthful colour and your hair.’ He sighed and smiled sadly. ‘But in the end, time is a noose around the neck, strangling slowly.’

Page 520

The way to the clothes shop led past the new Family Planning Centre, and Om slowed down, peering inside. ‘You said Thakur Dharamsi is in charge here?’ ‘Yes, and he makes a lot of money out of it.’ ‘How? I thought government pays the patients to have the operation.’ ‘The rogue puts all that cash in his own pocket. The villagers are helpless. Complaining only brings more suffering upon their heads. When the Thakur’s gang goes looking for volunteers, the poor fellows quietly send their wives, or offer themselves for the operation.’ ‘Hai Ram. When a demon like this is allowed to prosper, the world must really be passing through the darkness of Kaliyug.’ ‘And you tell me I am talking nonsense,’ said Om scornfully. ‘Killing that swine would be the most sensible way to end Kaliyug.’ ‘Calm down, my child,’ said Ashraf. ‘He who spits paan at the ceiling only blinds himself. For the crimes in this world, the punishment occurs in the Next World.’ Om rolled his eyes. ‘Yes, definitely. But tell me, how much money can he make from that place? The operation bonus is not very big.’ ‘Ah, but it’s not his only source. When the patients are brought to the clinic, he auctions them.’ ‘What does that mean?’ ‘You see, government employees have to produce two or three cases for sterilization. If they don’t fill their quota, their salary is held back for that month by the government. So the Thakur invites all the schoolteachers, block development officers, tax collectors, food inspectors to the clinic. Anyone who wants to can bid on the villagers. Whoever offers the most gets the cases registered in his quota.’

Note: It’s like Mukherjee says in the Gene. These are just ways to enforce and perpetuate current power structures

Page 540

But as Om began undoing the buttons, the officer ran and grabbed the waistband. ‘I forbid you to take off your clothes in my office. I am not a doctor, and whatever is in your pants is of no interest to me. If we start believing you, then all the eunuchs in the country will come dancing to us, blaming us for their condition, trying to get money out of us. We know your tricks. The whole Family Planning Programme will grind to a halt. The country will be ruined. Suffocated by uncontrolled population growth. Now get out before I call the police.’

Note: It’s for the greater good!