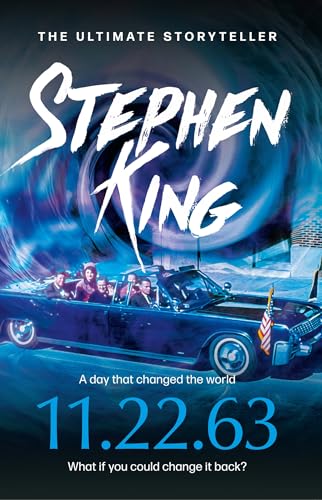

11.22.1963

by Stephen King

- Author:

- Stephen King

- Status:

- Done

- Format:

- eBook

- Genres:

- Fiction , Historical Fiction , Science Fiction , Time Travel , Horror , Fantasy , Thriller

- Pages:

- 849

- Highlights:

- 20

Review

Good book, interesting take on time travel.

Highlights

Page 33

Probably I would just die here, in a past for which a lot of people probably felt nostalgic. Possibly because they had forgotten how bad the past smelled, or because they had never considered that aspect of the Nifty Fifties in the first place.

Page 77

Would the kids have been kinder if they’d known the origin of the limp? Probably not. Although emotionally delicate and eminently bruisable, teenagers are short on empathy. That comes later in life, if it comes at all.

Page 89

If he didn’t die of DT-induced convulsions while he was in there, they’d turn him loose to start the next cycle. I found myself wishing my ex-wife was here – she could find an AA meeting and take him to it. Only Christy wouldn’t be born for another twenty-one years.

Note: The character knows this because his ex was an alcoholic. But SK knows this because he was an alcoholic.

Page 139

And did people believe it? The answer to that one was easy. It doesn’t matter if you’re talking 1958, 1985, or 2011. In America, where surface has always passed for substance, people always believe guys like Frank Dunning. 4

Note: No different in 2016 and 2024.

Page 152

I’m one of those people who doesn’t really know what he thinks until he writes it down, so I spent most of that weekend making notes about what I’d seen in Derry, what I’d done, and what I planned to do. They expanded into an explanation of how I’d gotten to Derry in the first place, and by Sunday I realized that I’d started a job that was too big for a pocket notebook and ballpoint pen. On Monday I went out and bought a portable typewriter.

Note: Like me fr fr

Page 159

I don’t know for sure, but I can tell you one more thing: there was something inside that fallen chimney at the Kitchener Ironworks. I don’t know what and I don’t want to know, but at the mouth of the thing I saw a heap of gnawed bones and a tiny chewed collar with a bell on it. A collar that had surely belonged to some child’s beloved kitten. And from inside the pipe – deep in that oversized bore – something moved and shuffled. Come in and see, that something seemed to whisper in my head. Never mind all the rest of it, Jake – come in and see. Come in and visit. Time doesn’t matter in here; in here, time just floats away. You know you want to, you know you’re curious. Maybe it’s even another rabbit-hole. Another portal. Maybe it was, but I don’t think so. I think it was Derry in there – everything that was wrong with it, everything that was askew, hiding in that pipe. Hibernating. Letting people believe the bad times were over, waiting for them to relax and forget there had ever been bad times at all. I left in a hurry, and to that part of Derry I never went back.

Note: It

Page 180

He was thinking. I could almost hear the wheels turning and the cogs clicking. Then a light went on in his eyes. Perhaps it was only the last remains of the sunset, but to me it looked like the candles that would now be flickering inside of jack-o’-lanterns all over town. He began to smile. What he said next could only have come from a man who was mentally ill … or who had lived too long in Derry … or both. ‘Gonna go after em, is he? Okay, let im.’ ‘What?’

Note: All the set up about Derry was necessary for this.

Page 210

She laughed. It was a terrific laugh. I bet people all over eastern Maine tuned in just to hear it. But when she spoke again, her tone was lower and all the humor had gone out of it. Sun to shade, just like that. ‘Who are you really, Mr Amberson?’ ‘What do you mean?’ ‘I do call-in shows on the weekends. A yard-sale show on Saturdays – “I’ve got a rototiller, Ellen, almost brand-new, but I can’t make the payments and I’ll take the best offer over fifty bucks.” Like that. On Sundays, it’s politics. Folks call in to flay Rush Limbaugh or talk about how Glenn Beck should run for president. I know voices. If you’d been friends with Harry back in the Rec days, you’d be in your sixties, but you’re not. You sound like you’re no more than thirty-five.’ Jesus, right on the money. ‘People tell me I sound a lot younger than my age. I bet they tell you the same.’ ‘Nice try,’ she said flatly, and all at once she did sound older. ‘I’ve had years of training to put that sunshine in my voice. Have you?’ I couldn’t think of a response, so I kept silent. ‘Also, no one calls to check up on someone they chummed around with when they were in grammar school. Not fifty years later, they don’t.’ Might as well hang up, I thought. I got what I called for, and more than I bargained for. I’ll just hang up. But the phone felt glued to my ear. I’m not sure I could have dropped it if I’d seen fire racing up my living room curtains. When she spoke again, there was a catch in her voice. ‘Are you him?’ ‘I don’t know what you—’ ‘There was somebody else there that night. Harry saw him and so did I. Are you him?’ ‘What night?’ Only it came out whu-nigh, because my lips had gone numb. It felt as if someone had put a mask over my face. One lined with snow. ‘Harry said it was his good angel. I think you’re him. So where were you?’ Now she was the one who sounded unclear, because she’d begun crying. ‘Ma’am … Ellen … you’re not making any sen—’ ‘I took him to the airport after he got his orders and his leave was over. He was going to Nam, and I told him to watch his ass. He said, “Don’t worry, Sis, I’ve got a guardian angel to watch out for me, remember?” So where were you on the sixth of February in 1968, Mr Angel? Where were you when my brother died at Khe Sanh? Where were you then, you son of a bitch?’ She said something else, but I don’t know what it was. By then she was crying too hard. I hung up the phone. I went into the bathroom. I got into the bathtub, pulled the curtain, and put my head between my knees so I was looking at the rubber mat with the yellow daisies on it. Then I screamed. Once. Twice. Three times. And here is the worst: I didn’t just wish Al had never spoken to me about his goddamned rabbit-hole. It went farther than that. I wished him dead.

Note: Heartbreaking. All that effort to shorten his life. I wonder if we’ll find out if his life ended up being longer or shorter.

Page 238

A loon cried somewhere, and was answered by a pal or a mate. Soon others joined the conversation. I shipped my paddle and just sat there three hundred yards out from shore, watching the moon and listening to the loons converse. I remember thinking if there was a heaven somewhere and it wasn’t like this, then I didn’t want to go.

Note: Looks are native to Maine! I checked just now.

Page 243

Andy Cullum put out his hand. ‘Next time we play for free, all right?’ ‘You bet.’ There was going to be no next time, and I think he knew that. His wife did, too, it turned out. She caught up to me just before I got into my car. She had swaddled a blanket around the baby and put a little hat on her head, but Marnie had no coat on herself. I could see her breath, and she was shivering. ‘Mrs Cullum, you should go in before you catch your death of c—’ ‘What did you save him from?’ ‘I beg pardon?’ ‘I know that’s why you came. I prayed on it while you and Andy were out there on the porch. God sent me an answer, but not the whole answer. What did you save him from?’ I put my hands on her shivering shoulders and looked into her eyes. ‘Marnie … if God had wanted you to know that part, He would have told you.’ Abruptly she put her arms around me and hugged me. Surprised, I hugged her back. Baby Jenna, caught in between, goggled up at us. ‘Whatever it was, thank you,’ Marnie whispered in my ear. Her warm breath gave me goosebumps.

Page 247

I saw people helping people. Two of them in a pickup truck stopped to help me when the Sunliner’s radiator popped its top and I was broken down by the side of the road. That was in Virginia, around four o’clock in the afternoon, and one of them asked me if I needed a place to sleep. I guess I can imagine that happening in 2011, but it’s a stretch. And one more thing. In North Carolina, I stopped to gas up at a Humble Oil station, then walked around the corner to use the toilet. There were two doors and three signs. MEN was neatly stenciled over one door, LADIES over the other. The third sign was an arrow on a stick. It pointed toward the brush-covered slope behind the station. It said COLORED. Curious, I walked down the path, being careful to sidle at a couple of points where the oily, green-shading-to-maroon leaves of poison ivy were unmistakable. I hoped the dads and moms who might have led their children down to whatever facility waited below were able to identify those troublesome bushes for what they were, because in the late fifties most children wear short pants. There was no facility. What I found at the end of the path was a narrow stream with a board laid across it on a couple of crumbling concrete posts. A man who had to urinate could just stand on the bank, unzip, and let fly. A woman could hold onto a bush (assuming it wasn’t poison ivy or poison oak) and squat. The board was what you sat on if you had to take a shit. Maybe in the pouring rain. If I ever gave you the idea that 1958’s all Andy-n-Opie, remember the path, okay? The one lined with poison ivy. And the board over the stream.

Note: A lesser writer would have forgotten to add this or found it too awkward to bring up.

Page 249

Sometimes I cursed Al for forcing me into this mission willy-nilly, but in more clearheaded moments, I realized that extra time wouldn’t have made any difference. It might have made things worse, and Al probably knew it. Even if he hadn’t committed suicide, I would only have had a week or two, and how many books have been written about the chain of events leading up to that day in Dallas? A hundred? Three hundred? Probably closer to a thousand. Some agreeing with Al’s belief that Oswald acted alone, some claiming he’d been part of an elaborate conspiracy, some stating with utter certainty that he hadn’t pulled the trigger at all and was exactly what he called himself after his arrest, a patsy. By committing suicide, Al had taken away the scholar’s greatest weakness: calling hesitation research.

Page 253

Later that month, the principal called me into his office, offered some pleasantries and a Co’-Cola, then asked: ‘Son, are you a subversive?’ I assured him I was not. I told him I’d voted for Ike. He seemed satisfied, but suggested I might stick more to the ‘generally accepted reading list’ in the future. Hairstyles change, and skirt lengths, and slang, but high school administrations? Never.

Note: To be fair to the principal, there was an actual red scare around that time.

Page 262

There were billboards advocating the impeachment of Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren; billboards showing a snarling Nikita Khrushchev (NYET, COMRADE KHRUSHCHEV, the billboard copy read, WE WILL BURY YOU!); there was one on West Commerce Street that read THE AMERICAN COMMUNIST PARTY FAVORS INTEGRATION. THINK ABOUT IT! That one had been paid for by something called The Tea Party Society. Twice, on businesses whose names suggested they were Jewish-owned, I saw soaped swastikas.

Page 275

Oh, I told myself lots of things, and they all boiled down to the same two things: that it was perfectly safe, and that it was perfectly reasonable to want more money even though I currently had enough to live on. Dumb. But stupidity is one of two things we see most clearly in retrospect. The other is missed chances.

Page 350

Home is watching the moon rise over the open, sleeping land and having someone you can call to the window, so you can look together. Home is where you dance with others, and dancing is life.

Page 427

‘He said there’s a rumor that there’s going to be some sort of major deal in the Caribbean this fall or winter. A flashpoint, he called it. I’m assuming he meant Cuba. He said, “That idiot JFK is going to put us all in the soup just to show he’s got balls.”’ I remembered all the end-of-the-world crap her former husband had poured into her ears. Anyone who reads the paper can see it coming, he’d told her. We’ll die with sores all over our bodies, and coughing up our lungs. Stuff like that leaves an impression, especially when spoken in tones of dry scientific certainty. Leaves an impression? A scar, more like it. ‘Sadie, that’s crap.’ ‘Oh?’ She sounded nettled. ‘I suppose you have the inside scoop and Senator Kuchel doesn’t?’ ‘Let’s say I do.’ ‘Let’s not. I’ll wait for you to come clean a little longer, but not much. Maybe just because you’re a good dancer.’ ‘Then let’s go dancing!’ I said a little wildly. ‘Goodnight, George.’ And before I could say anything else, she hung up.

Note: Bad writing. There’s no reason this information would put her in danger. I think it’s just easier for him to write if the protagonist is solo.

Page 722

I don’t know, I don’t know. Here’s another thing I do know. The past is obdurate for the same reason a turtle’s shell is obdurate: because the living flesh inside is tender and defenseless.

Page 731

eighty now, but some faces you don’t forget. The photographer might have suggested that she turn her head so the left side was hidden, but Sadie faced the camera head-on. And why not? It was an old scar now, the wound inflicted by a man many years in his grave. I thought it lent character to her face, but of course, I was prejudiced. To the loving eye, even smallpox scars are beautiful.

Page 739

Some people will protest that I have been excessively hard on the city of Dallas. I beg to differ. If anything, Jake Epping’s first-person narrative allowed me to be too easy on it, at least as it was in 1963. On the day Kennedy landed at Love Field, Dallas was a hateful place. Confederate flags flew rightside up; American flags flew upside down. Some airport spectators held up signs reading HELP JFK STAMP OUT DEMOCRACY. Not long before that day in November, both Adlai Stevenson and Lady Bird Johnson were subjected to spit-showers by Dallas voters. Those spitting on Mrs Johnson were middle-class housewives. It’s better today, but one still sees signs on Main Street saying HANDGUNS NOT ALLOWED IN THE BAR. This is an afterword, not an editorial, but I hold strong opinions on this subject, particularly given the current political climate of my country. If you want to know what political extremism can lead to, look at the Zapruder film. Take particular note of frame 313, where Kennedy’s head explodes.

Note: Boy I’m really looking forward to visiting Dallas next year for a week.